There’s No Such Thing as a Worthless Book

Japan is different from all other First World countries, Edward Luttwak argues in The London Review of Books, and has forged its own foreign policy since the end of the Second World War, sometimes to the consternation of America: “One can fly to Japan from anywhere, but from Japan one can only fly to the Third World, and it hardly matters whether one lands in Kinshasa, London, New York or Zurich: they are all places where one must be constantly watchful and distrustful, where one cannot leave a suitcase unattended even for ten minutes, where women strolling home through town at 3 a.m. are deemed imprudent, where the universal business model is not to underpromise and overdeliver but if anything the other way round, where city streets are clogged at rush hour because municipal authorities mysteriously fail to provide ubiquitous, fast and comfortable public transport, where shops need watchful staff or cameras against thieving customers, and where one cannot even get beer and liquor from vending machines that require no protection from vandalism. Japan was the world’s only really different country when I first visited forty years ago, and it remains so now, despite many misguided attempts to internationalise its ways to join the rest of the world.”

Archeological evidence of battle that gave birth to the Roman Empire proves historians right: “It’s always been thought that many of Cleopatra and Mark Antony’s ships were bigger than Octavian’s – and were therefore less manoeuvrable. But now crucial archaeological data obtained from the victory monument excavations over recent years has provided the first archaeological confirmation that some of Cleopatra and Mark Antony’s ships were indeed unusually large. This would have given Octavian – who had smaller, faster vessels – a history-changing advantage.”

The popular poetry of Elizabeth Jennings: “More than Philip Larkin or even John Betjeman (both good popular poets), Jennings was the darling of the general reader, or what Samuel Johnson called the common reader, by whose ‘common sense… uncorrupted by literary prejudice… must finally be decided all poetical honours.’ Certainly, Michael Schmidt was right to claim that his bestselling Carcanet author was ‘the most unconditionally loved writer’ of her generation. Writing of the things that preoccupy most readers – family, faith, love, loss, illness, hope, atonement, redemption – she not only won her readers’ trust but their affection. In light of the many false reputations that disfigure our literary landscape, Jennings’ unfashionably popular work is tonic, especially since so much of its appeal derives from its Catholic character.”

Where is Walter Benjamin’s lost suitcase (and the manuscript it may have contained)? “When Walter Benjamin fled France in 1940, he took a heavy black suitcase. Did it contain a typescript? Where is it now?”

Free throws should be easy, so why do so many basketball players miss? Newsflash: “Getting a player to shoot not just consistently but properly has little to do with their inborn talent or athleticism, and almost everything to do with hard work.”

Adeline A. Allen reviews Heather Mac Donald’s The Diversity Delusion: “Mac Donald’s book is right on point, but it is also biting in tone, brimming with exasperation and anger. Of course, the topic is a frustrating one, and Mac Donald has good reason to be angry after having been a target of campus hysteria—twice. But her tone may define and confine her audience. Those who are already inclined to pick up her book will be enriched in knowledge and fortified in conviction, but those not so inclined may only double down. Mac Donald is at her finest when she offers an ode to the humanities, reminding the reader of the wonder and sublimity in Shakespeare and Bach, the truth and timelessness in Homer and Plato. In so doing, she sounds a clarion call for the university to disabuse itself and all of us of delusion and return to ‘the search for objective knowledge that takes the learner into a grander universe of thought and achievement.’”

Essay of the Day:

In Standpoint, Theodore Dalrymple argues that no book is worthless and reads a romantic novel in paperback to prove it:

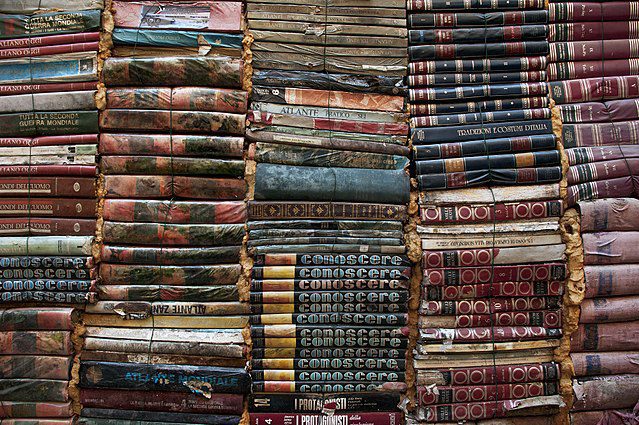

“It might be objected that the books to be found in my study, even at random, are unlikely to be utterly valueless to me, for I selected them all myself. To meet this objection to my thesis that every book has something of worth to the reader, I asked my wife to go to the nearest Oxfam shop — Oxfam shops being to British high streets what rats are to urban dwellings: you are never more than a few yards from one — and buy at random an airport novel of the kind that people donate to Oxfam under the misapprehension that, while disembarrassing themselves of household clutter, they are thereby assisting the people of the Third World. Oddly enough, among the pulp novels, biographies of Beckham and discarded cookbooks is often to be found a work of arcane or specialised academic interest, my latest purchase of that description being a multiauthor book on encephalitis lethargica, the mysterious disease whose cause is even more disputed than that of the First World War, which it followed.

“My wife returned with a copy of Her Frozen Heart by Lulu Taylor, a best-selling author of whom I had not previously heard. I had asked her to choose at random a well-preserved paperback from among the rows of disposable romantic novels (I have a neurotic distaste for reading paperbacks in bad condition, whatever the merit of the content) to be found on the shelves of all charity shops, with their garish vulgar covers of the kitschiest possible design of a type which presumably appeals to and reflects — oh horrible thought — the taste of the public. It was, unfortunately, 483 pages long, and therefore gave rise to an experiment somewhat longer than I had wanted or anticipated.”

Photo: Antigua

Poem: James Matthew Wilson, “In the Cry Room”

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments