Blaspheming St. Rachel Held Evans

A reader asked in the comments last night if I intended to comment on the death of Rachel Held Evans, the iconic progressive Evangelical (or rather, ex-Evangelical; I recall that she ceased to identify with the label) who died tragically at the age of 37. I said no, that I don’t know enough about her writing to write intelligently about her legacy. She and I had clashed publicly about theology, but all of that is rightly set aside in the face of illness and death. When I heard that she was in the hospital, I tweeted out a request for all my followers to pray for her and her family. Similarly, when I was overseas last week and heard that she had died, I tweeted out an expression of sorrow and condolence, and once again invited prayers for her and for those who love her. I didn’t feel it necessary to say more.

On my long trip back to the US yesterday, I noticed that my friend John Stonestreet, a leading conservative Evangelical, had written a beautiful response to her death, published in Christianity Today. Earlier in his life, John had known and worked with Rachel and her husband Dan Evans. Their public ministries took divergent turns as Rachel moved to the theological and cultural left, and John’s appreciation of her life observed that. In fact, he had appeared in one of her books as “Greg the Apologist.” In the end, his piece was a true appreciation, written with obvious respect and affection. The Atlantic‘s Emma Green, in explaining the effect RHE had on the US religious landscape in her 15 years of writing, said:

Even as Evans rejected certain traditionalist notions of Christianity, often throwing herself into the middle of intense fights over race, gender, sexuality, and politics, she retained the respect of her adversaries. In the days following her death, conservative Christian figures—from the Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore to the blogger and provocateur Matt Walsh—have expressed their shock and shared their condolences for her family. Beth Moore, one of the most popular female Bible teachers in the country, wrote on Twitter that she was “thinking [about] what it was about [Evans] that could cause many on other sides of issues to take their hats off to her in her death. People are run rife with grief for her babies, yes. But also I think part of it is that, in an era of gross hypocrisy, she was alarmingly honest.” Her friends and allies shared this grief, and more: Over the weekend, many people posted personal stories about Evans’s kindness online, which were shared thousands of times.

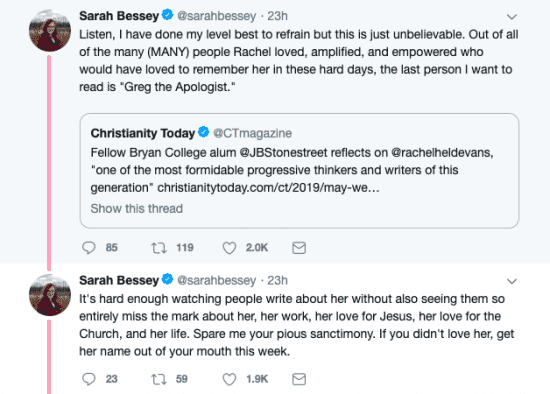

So, I was genuinely shocked to see John excoriated by progressives on social media for daring to speak words of criticism about RHE, even in the context of an affectionate remembrance. For example:

There is a lot of that going around. A Yellowstone geyser of it, in fact.

John Stonestreet eventually took his essay down after word reached him that at least one member of RHE’s family had been hurt by what he wrote. It tells you something about John Stonestreet’s character that he did this. Christianity Today editor Mark Galli, apologizing for having published the essay, wrote:

Evans was admired by many for good reasons. When I finished Stonestreet’s piece, I came away thinking he deeply respected and admired Evans despite their serious differences.

But as I re-read the piece later, I realized there were problems I should have caught. We now see that what was intended to be a tribute came across as overly negative and not framed well. Stonestreet’s piece was well-intentioned, but one of the jobs of an editor is to help authors see how their piece will read to a larger audience. I failed to do that. And as a result, we inadvertently antagonized many who deeply loved Evans.

So, we apologize for publishing a piece that created anger or exacerbated grief over Evans’s untimely death.

OK, but as someone who did read the essay, I think one thing that gave it such power was that it was clear that Stonestreet, who is a leading conservative Evangelical (and someone RHE once thanked for being her “teacher”), did, in fact, deeply respect her despite their serious differences. I finished the essay thinking that I hope one day, when I die, that I’ve conducted myself in such a way that progressive Christians, who think I’m seriously wrong about some serious issues, will write a remembrance like that about me.

The issues that divide me from progressives (Christian and otherwise) are non-trivial, neither to me nor to them. I would never expect them to pretend that my own writing and advocacy was worthy of admiration when they agreed with it, but in the wake of my death, not something worthy of comment. Frankly, I would find it much more respectful if they clearly noted that we disagreed on important matters. If, for example, Andrew Sullivan were to predecease me, the essay I would write about his life and legacy would be about what I regard as the good and the bad of his public life, but would focus more on the good, because that’s honestly how I see him. If I tried to make him into a saint, I could see him rolling his eyes. Because I love him as a friend (and sometimes a frenemy), I would tell the truth about him, as best I could; my greatest hope would be that if he wrote a postmortem remembrance of me, he would do the same thing. A hagiographical postmortem take on me from a Christian writer with Andrew Sullivan’s convictions would be fundamentally dishonest, and I solemnly swear that if he does such a thing — Sully is not capable of it, but it he were to do that — then I will haunt him until he retracts it.

Seriously, though, I do not understand this intolerance we have developed for critical analysis of the dead. Love her or not, Rachel Held Evans stood for controversial things in the public square. She made a difference. She was not milquetoast, which is why so many people had strong views on her. To write nastily about her days after her tragic passing would be a cruel and graceless act. But it is an act of generosity for her theological opponents to recognize her errors, as they see them, within a statement of appreciation. If her life had not mattered, and mattered greatly, nobody would care.

I am not writing about RHE here. She was not part of my world. I had some unpleasant social media clashes with her over the years, but they were relatively minor. She released a tweetstorm condemning my book The Benedict Option on spurious grounds, which I responded to here. In my response, I admitted that I don’t know much about her thinking, but from what I’ve read about her over the years, she strikes me as “an anti-fundamentalist reactionary.” Excerpt:

In the interview that RHE cites at the start of her Twitter thread, I say:

Trump is in fact no answer to the crisis. He’s a symptom of the crisis we’re in.

But you know what? So is Rachel Held Evans. In fact, from what I can tell of her thinking and her influence, I think she may be a more acute symptom of cultural breakdown within the Christian church than Trump. Why? Because with her Church Of What’s Happening Now-style progressivism, she represents the hollowing-out of Christianity by Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. I wonder if there’s a single major point on which her theological and moral views clash with the opinions held by secular progressives.

Well, that was 2017. Again, I’ve never read her books, and I therefore don’t know enough about what she stood for and how she stood for it to make a judgment about her legacy one way or the other. I thought her dismissal of my work was at best uninformed, but even if she had read my book, I certainly would not have expected a progressive Christian like her to agree with it. Nor did any of our past clashes matter to me when I first heard that she was seriously ill. Whatever your theological views, if your heart doesn’t break in the face of a woman — a wife and mother — dying so young, then you might not have a heart.

Just so we’re clear: if you believe that it’s morally wrong for people to respond to the death of RHE by tearing into her legacy viciously, then I agree with you. There may be a time for doing that, but four or five days after she is dead is not that time. It’s a matter of respect. But if you believe that there is no morally acceptable way to write critically about her legacy so soon after her passing, well, we’ve got a problem.

So I’m not writing about RHE, but I am writing about writing about RHE. Who has the right to forbid criticism of her or any public figure after they die? A conservative Evangelical writer named Anne Kennedy writes about writing about RHE. She says:

This is an awkward moment for the evangelical world. It is a moment long coming, and one that many Christians who have lived through the quiet earthquakes along the fault-lines within mainstream Christianity have dreaded, knowing how it goes, but one that cannot be avoided any longer. I suppose we should even welcome it for its ever increasing clarity.

If the election of Mr. Trump was one kind of evangelical crisis, the death of Rachel Held Evans is another. Both brought into the light the deep-rooted troubles that have been long growing. Both are forcing Christians to show to themselves, and to each other, and to the world, their true theological cards.

On Sunday, Kennedy posted something indirectly about RHE, and about her own struggles with RHE’s influence among Evangelicals, which she (Kennedy) believes turned people away from the truth. It was respectful but critical. Well, in the new post, Kennedy quotes a “kind” (her word) comment from one of her readers, remarking on her (Kennedy’s) first post about RHE’s life and legacy. Kennedy’s reader said that Kennedy seemed to read RHE out of the church over RHE’s various stands. The reader:

Perhaps I read too much into what you said. Anne, we’re all in Christ, eating at the same table, though perhaps you and Rachel are at different ends of it. I hope you’ve been reading the deluge of tweets from people who decided to stay in the church or who went into ministry or learned to love others better because of Rachel. It’s an astounding testament to God’s speaking through her…All of this to say that I’d really like it if you’d reconsider your take on her. She’s one of us.

In her response, Kennedy writes gently but firmly, saying that

some churches cease being true biblical churches when they willingly and purposefully embrace teaching contrary to that same bible.

This isn’t to say that everyone inside of those churches is then not a Christian, nor that no church can have any error to be a real church, but rather that some teachings are big enough to set a church, and certainly individuals within the church, outside of ‘the bounds of orthodoxy.’ Which is to say they are no longer truly Christian.

Kennedy goes on to explain why, in her view, RHE had departed so far from the core teachings of the historic Christian faith that she had departed the church. In particular, Kennedy mentions RHE’s radically affirmative views on LGBT. Kennedy goes on:

I left the Episcopal church—probably as Rachel was entering it—for this reason: it looks inviting to say that everyone is welcome as they are, no questions asked, but it is actually cruel. In so far as inviting someone in out of a snowstorm, but then opening all the windows and doors, so that the furious icy snow comes in with them, is cruel. There is a reason the human heart longs for the warm shelter of the church—because inside the heating fire of God’s atoning grace binds sinners together in one holy fellowship. But the sin has to stay outside, and we can’t change the definition of sin to make it easier.

And so we are not sitting at opposite sides of one long table. We are not eating of the one bread and drinking out of the one cup. We are talking about two different faiths, two different kinds of love, two different lords.

Christians who love sinners, as Christ has commanded them to do, must speak the truth about who that God is, and who we are as his creatures. Moreover, we ought to pray that those who are walking away from his warm and gracious mercy will turn around, will repent, will walk back toward him. And that when they come to the haven of the church, the church does not throw away that mercy by saying that it is something other than what it really is.

Read the whole thing. Anne Kennedy is right about the unfathomable importance of these questions. I would not presume to judge whether or not RHE is in Paradise — that’s God’s decision — but I pray for His mercy on her, as I pray for His mercy on all who die (because I will need that mercy myself at the hour of my judgment). But this is not really about the eternal disposition of RHE’s soul. This is about what it means to be a Christian, and what it means to be a church. For Christians, these are the most serious questions there can be. As Kennedy puts it, when we discuss what Christians are required to believe, how we know what the Truth is, and how all of us are required to respond to that Truth, “We are talking about two different faiths, two different kinds of love, two different lords.”

As I’ve tried to say in this space over the years, I understand why Christians like RHE, who believe that there is nothing sinful about homosexuality, are so angry at churches and individual Christians who hold to what is plainly in Scripture, and what has been clear in the apostolic tradition until pretty much the day before yesterday. If I believed what they believed, then yes, changing the church would be a matter of basic justice. What so many of the people on that side cannot seem to grasp is that for the things they believe about LGBT to be true, they have to do such radical revision to fundamental Christianity that they render it into essentially a different religion. I struggle too to decide where to draw the line between what is mistaken but still within the Christian church, and what goes too far. It’s not about wanting to exclude people out of meanness. It’s rather about believing that the Christian faith is a revelation about the things that truly are. It’s about believing that the Bible is a reliable roadmap for finding our way out of the dark wood, and that the Church is a trustworthy guide. If we come to believe that we have the right to choose any map and any guide that pleases us, because in the end, we’re all going to the same place, and what matters is only how enjoyable the journey is — well, we are going to be lost, perhaps for all eternity.

A couple of years back, Tish Harrison Warren, who is a priest in the Anglican Church of North America, and nobody’s idea of a political conservative, published a powerful essay about the role of authority (and its lack) in contemporary Christian life and discourse. She focused on the Jen Hatmaker phenomenon, but this could all be applied to RHE. Warren wrote:

Providing ecclesial oversight does not mean that all writers will speak out of one narrow tradition. Nor does ecclesial affiliation itself ensure orthodoxy—there is, of course, no silver bullet against false teaching. Nevertheless, without institutional accountability there is simply no mechanism by which we as a church can preserve doctrinal fidelity.

The New Testament presupposes that church authority, hierarchy, and discipline exist to protect orthodoxy and orthopraxy. This responsibility does not cease in this age of the internet. Orthodox church institutions that value scriptural and historical faithfulness have a responsibility to provide clear guidance to Christian readers and listeners who are seeking to discern which voices to heed in the din of cyber-spirituality.

What she wrote about Jen Hatmaker could equally be applied to RHE, who was not theologically trained or accountable to anybody. Despite that, RHE was so influential that not even her opponents would deny what her friend Laura Turner wrote after her death: “For those who are not so familiar with the culture of evangelical Christianity, it is hard to overstate the impact Rachel Held Evans had on it.”

If you have the time, I commend to you this important 2016 essay by the Evangelical theologian Alastair Roberts, who talks about the erosion of trust, the rise of Donald Trump, and the new prominence of voices like RHE’s and Jen Hatmaker’s. They are “super-peers.” He writes:

The power of these ‘super-peers’ is the power of trust. Many of these ‘super-peers’ are advocates for women, who contrast with the pastors and churches they believe have betrayed them (most recently in their open support for the misogynist Trump). They give voice to truths that have been officially suppressed or downplayed—to the truth of women’s sense of marginalization in the Church and to the truth of abuse. These ‘super-peer’ women are ‘peers’ who are relatable and likeable, who form close communities and ideological consensuses around themselves. They are typically near in age to most of their followers, not least because there is a crisis of alienation between the generations in many churches, and people are looking for leaders of their own generation, rather than attending to fathers and mothers in the faith.

As they are the key influencers within their communities, they are appropriately termed ‘super-peers’. They represent a peculiar kind of populist leader, leaders who illustrate the way in which our determination of truth depends on more than merely narrow concerns of accuracy and veracity.

Whereas in the past, communities of trust would tend to be locally based, typically rooted within church congregations, extended families, workplaces, and neighbourhoods, in the age of the Internet, communities of trust are increasingly abstracted from locality. Twenty or thirty years ago, one’s community of faith would primarily have been found in one’s local congregation, and would have been overseen by pastors and church leaders. Nowadays, our communities of faith are much more diffuse and much less pastorally guided. Where once pastors, church leaders, and mature Christians could keep watch over a congregation, ensuring that error didn’t creep in, this is much harder to do today. Likewise, dissenting and disaffected persons are much more able to form their own independent communities online.

Jen Hatmaker is a good illustration of some of these dynamics. Hatmaker isn’t a trained theologian, yet her changed position on same-sex marriage has recently received an immense amount of discussion among Christians. In some respects, there isn’t a huge difference between Hatmaker on same-sex marriage and a celebrity anti-vaxxer who has claimed to have extensively ‘researched’ the issue. In both cases, even supposing they were correct, the person’s position is of little academic worth (because they only have very limited ability to engage in first-hand research themselves). Nevertheless, it is of deep social consequence and danger. The opinions of such persons hold weight on account of their popularity, likeability, and people’s instinctive trust of them, whereas the official authority figures challenging them are distrusted, despite their greater learning.

To understand the future of evangelicalism, there are few things more important than attending to currently shifting networks of trust. If people are confident that evangelicalism will generally be opposed to same-sex marriage in twenty-five years’ time, for instance, I wonder whether they have been paying close attention to the movements that have been taking place. The most prominent voices that have opposed same-sex marriage are now regarded with deep distrust from many quarters, especially by the younger generations, not least on account of their politics and the abuse scandals that have tarnished their reputation. People no longer trust them as leaders, so their position on same-sex marriage is now thrown into greater question. Although they may officially have authority, practically they have little authority over the younger generations. Most of us have LGBT persons in our families and friendship groups and many of us have a much closer bond with them than with an older generation of Christian leaders. Many people’s trust in Scripture’s power to speak to issues of gender and sexuality has also been damaged through the influence of purity culture and the often hateful extremism and callousness that they associate with traditional evangelicals’ opposition to homosexual practice and same-sex marriage.

Again, younger generations have grown up and live in a context of overwhelming information and competing gatekeepers. As a result, they have learned to function more as independent theological and religious consumers, assembling their own faith through picking and choosing among authorities. As much biblical and theological reasoning lies beyond the power of their independent understanding, yet they must now determine what positions to hold based on their own research, they are increasingly inclined to treat theological positions whose truth lies beyond their power to determine as adiaphora [matters not essential to the faith, and therefore tolerable within the church — RD]. Alternatively, they introduce different criteria for assessing truthfulness, criteria more amenable to minds without rigorous theological education, privileging impressions or their sense of what is most ‘loving’. In such a context, a heavily contested view such as the legitimacy of same-sex marriage is likely to come to be regarded as optional by many.

Any figure within the culture of a church or religion who is as influential as Rachel Held Evans is going to receive criticism, some of it unfair. Did RHE use her immense influence for good or bad, on the whole? How you answer that question depends on what you think Christianity is. It is a perfectly legitimate question, and an important one. RHE was one of the most influential Christians of our time, in large part because she was such a powerful embodiment of the spirit of our time (in ways that Tish Harrison Warren and Alastair Roberts discern). She was a progressive Christian, and the champion of progressive Christian causes. But they don’t own her.

UPDATE: An interesting reflection by reader Dana Ames:

I spent +30 years as an Evangelical. I was on my way into Orthodoxy as Rachel’s star was rising. I read her blog faithfully until she stepped over the line about which Rod writes, but I continued to check it every once in a while to see what Rachel was working on next. I believe she remained a Christian and could affirm the Nicene Creed. I also believe she became confused about something important, as pretty much everyone is right now in the Western world.

Rachel had the following she did because she was a good writer who exuded real honesty, and was asking questions Evangelicals were thinking but were often afraid to say out loud because of the inability of those in authority in Evangelical institutions to engage with those questions. More often than not, bringing up those questions to your pastor has resulted in your faith being questioned, or you being patted on the head patronizingly (especially if you are a woman), or you being told to just read your Bible and pray more and participate in church functions more; or all of the above. Some Evangelicals, beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, were getting tired of evasions and pat answers. Rachel was one of them and was willing to talk about things that those authorities were avoiding or incapable of addressing.

Conservative (but not partisan) Evangelical theologians including Scot McKnight, Roger Olson and Mark Noll have for years pointed out that there are theological difficulties in today’s Evangelicalism that are not being addressed because of a) a lack of vocational academic theologians and b) the thin-ness of theological thought about some of the more important doctrines including ecclesiology and the Trinity. In addition, Evangelicalism has for a long time been marked by a streak of anti-intellectualism. Especially in recent years, fewer Evangelical pastors and congregations have found a theological course of study to be necessary for “hearing God” and “preaching the Gospel”. “Critical analysis” is a part of the mental geography only of the small number of professional Evangelical theologians in rigorous academic settings.

Rachel was not an anti-intellectual; she was very intelligent and could form understandable logical arguments. She graduated with a degree from an Evangelical college. However, the kind of Evangelical institution she attended sits uneasily within Evangelicalism because of this anti-intellectual streak. Combined with our culture’s general tendency to steer our lives by how we feel about things, I would say most Evangelicals simply don’t have the ability to put forward an argument – other than “the Bible says” – for the reasons for sexual continence, and for many other Christian teachings as well. This is one large reason why young Evangelicals have become MTDs.

I think Rachel became a Progressive Christian because she was a kind person; she wanted Christians to be kind to those she believed were excluded, moved from one thin theology to another that supposedly justified that kind of inclusion, and found friendships and intellectual and other kinds of support among other Protestants who had also moved in that direction. Many of the problems of Evangelicalism she highlighted, other than the issues around sexuality, have been real problems that the majority of Evangelicals have not yet managed to adequately address in theology and praxis. If there is any blame to be cast for Rachel’s “drift”, in my view a large portion of it falls into the lap of conservative American Evangelicals and their ineptitude in addressing all of issues she highlighted in her work.

UPDATE: I’ve just arrived in Washington, and found this e-mail in my in-box:

Dear Mr. Dreher,

Your improper use of the portrait of Rachel Held Evans in the piece authored by you for The American Conservative (https://theamericanconservative.com/dreher/blaspheming-st-rachel-held-evans/?) is unauthorized and copyright infringement. Please remove promptly before we seek further legal action.

Sincerely,Daneen

Golly. It has been removed. I apologize for using it. I assumed wrongly that because it had been put out on social media by Daneen Akers (see below) that it was in the public domain. But Lord have mercy, progressive Christians, you don’t have to threaten to sue me to get me to take things like this down.

Here's the portrait of @rachelheldevans for the @HolyTroubleBook book, finished last night w/love & tears by @GillGamble. The etching of her halo reads "Eshet Chayil, Woman of Valor." What a woman of valor she was. May we be the people she believed in. #SaintRachel #BecauseOfRHE pic.twitter.com/ysWGSB1d4z

— Daneen Akers (@daneenakers) May 7, 2019