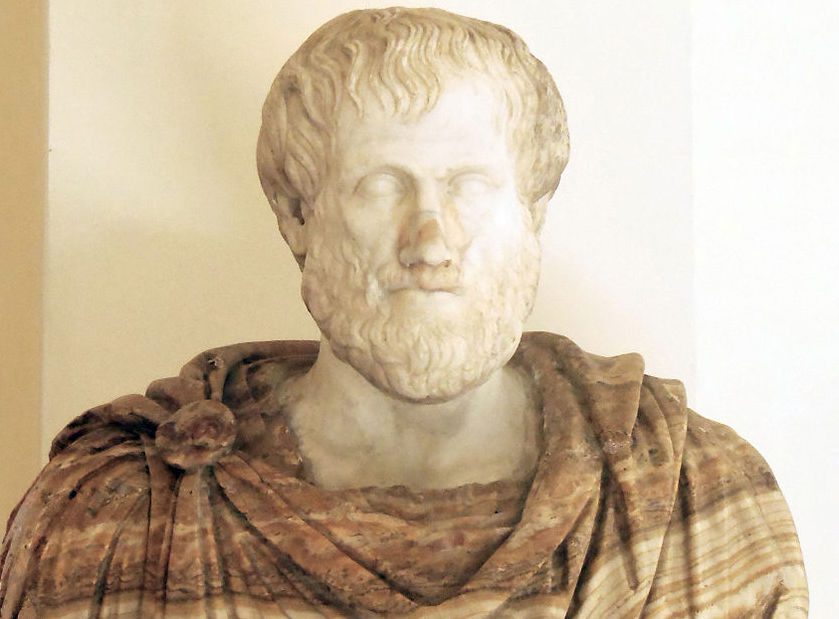

Should We Cancel Aristotle?

Agnes Callard offers—at first—a lukewarm defense of Aristotle in The New York Times, but then she turns up the heat:

There is a kind of speech that it would be a mistake to take literally, because its function is some kind of messaging. Advertising and political oratory are examples of messaging, as is much that falls under the rubric of ‘making a statement,’ like boycotting, protesting or publicly apologizing.

Such words exist to perform some extra-communicative task; in messaging speech, some aim other than truth-seeking is always at play. One way to turn literal speech into messaging is to attach a list of names: a petition is an example of nonliteral speech, because more people believing something does not make it more true.

Whereas literal speech employs systematically truth-directed methods of persuasion — argument and evidence — messaging exerts some kind of nonrational pressure on its recipient. For example, a public apology can often exert social pressure on the injured party to forgive, or at any rate to perform a show of forgiveness. Messaging is often situated within some kind of power struggle. In a highly charged political climate, more and more speech becomes magnetically attracted into messaging; one can hardly say anything without arousing suspicion that one is making a move in the game, one that might call for a countermove.

For example, the words ‘Black lives matter’ and ‘All lives matter’ have been implicated in our political power struggle in such a way as to prevent anyone familiar with that struggle from using, or hearing, them literally. But if an alien from outer space, unfamiliar with this context, came to us and said either phrase, it would be hard to imagine that anyone would find it objectionable; the context in which we now use those phrases would be removed.

In fact, I can imagine circumstances under which an alien could say women are inferior to men without arousing offense in me. Suppose this alien had no gender on their planet, and drew the conclusion of female inferiority from time spent observing ours. As long as the alien spoke to me respectfully, I would not only be willing to hear them out but even interested to learn their argument.

I read Aristotle as such an ‘alien.’ His approach to ethics was empirical — that is, it was based on observation — and when he looked around him he saw a world of slavery and of the subjugation of women and manual laborers, a situation he then inscribed into his ethical theory.

When I read him, I see that view of the world — and that’s all. I do not read an evil intent or ulterior motive behind his words; I do not interpret them as a mark of his bad character, or as attempting to convey a dangerous message that I might need to combat or silence in order to protect the vulnerable. Of course in one sense it is hard to imagine a more dangerous idea than the one that he articulated and argued for — but dangerousness, I have been arguing, is less a matter of literal content than messaging context.

What makes speech truly free is the possibility of disagreement without enmity, and this is less a matter of what we can say, than how we can say it. ‘Cancel culture’ is merely the logical extension of what we might call ‘messaging culture,’ in which every speech act is classified as friend or foe, in which literal content can barely be communicated, and in which very little faith exists as to the rational faculties of those being spoken to.

Speaking of cancel culture, most Americans are against it, Politico reports, though Democrats are apparently more likely to participate in it than Republicans and young people have a far more positive view of it than older folks: “Members of Generation Z are the most sympathetic to punishing people or institutions over offensive views, followed closely by Millenials, while GenXers and Baby Boomers have the strongest antipathy towards it. Cancel culture is driven by younger voters. A majority (55%) of voters 18-34 say they have taken part in cancel culture, while only about a third (32%) of voters over 65 say they have joined a social media pile-on.”

In other news: What should we make of J. M. Coetzee’s Jesus, B. D. McClay asks in a review of his Jesus trilogy— The Childhood of Jesus, The Schooldays of Jesus, and The Death of Jesus: “The biggest surprise in The Death of Jesus is how much of the book remains after Davíd dies. There is the faint expectation that something incredible will happen, something that could not have been anticipated, not a resurrection of course but something like one, a humanist reply. But instead the book seems to continue only so that you can be sure that nothing happens, nothing will happen, and nothing, really, could. Simón’s name is significant in two senses. There is the old man who recognizes Christ, mentioned before. There is also, more obviously, Simon Peter, the disciple Christ renames and then founds his church on. But our Simón stays Simón to the end. Upon him, nothing can be founded. For Coetzee, the post-religious condition is the condition, the whole problem of modern man. There was a time when humanism could plausibly replace God, but that time is past; literature and the arts cannot possibly claim to provide a window to eternity. This is why Coetzee’s savior, in The Death of Jesus, does not manage to leave behind a sacred text, or even an apostle. All he leaves behind is Don Quixote, a book that is, for Simón, ‘a relic of some kind.’”

A short history of the word meh and its meaning: “In Yiddish, which is (though there are still some who insist on questioning it) the clear source of the word, meh functions only as an interjection, never as an adjective. The incomparable Leo Rosten, who lists it under the variant form of mnyeh in his 1982 Hooray for Yiddish, gives the following twelve meanings for it: 1. ‘N-no.’ 2. ‘So?’ 3. ‘Maybe (but I think not).’ 4. ‘Who knows?’ 5. ‘What difference does it make?’ 6. ‘I should live so long,’ 7. ‘You should live so long.’ 8. ‘Tell it to Sweeney.’ 9. ‘Nonsense.’ 10. ‘That’s what you say.’ 11. ‘That’s what he (she) says.’ 12 ‘Oh, well . . . ’”

Andrew Fox writes about how the writer Barry N. Malzberg showed him that science fiction “was just Judaism in a spacesuit”: Science fiction is just Judaism in a spacesuit. If the statement strikes you as ridiculous, consider the evidence. Both cultures began life on the margins, the domain of small and mocked minorities who looked at the world from the outside and who survived by adhering to their own intricate traditions. Both cultures are, first and foremost, an exercise in ‘what if,’ Judaism forever looking forward to the coming of the Messiah and having its adherents pray daily for the rebuilding of the Temple, and science fiction imagining the life that lies just at the cusp of the possible. And both cultures stand at risk of being loved out of existence, embraced mightily by the mainstream, sailing precariously between the Scylla of assimilation and the Charybdis of dilution. Any Jew looking worriedly at the rising rates of intermarriage, say, knows exactly what fans of True Quill science fiction—prose science fiction written to extrapolate technological and social trends and intelligently comment on modern society—have felt since 1977, when Star Wars burst upon the screens of the nation’s multiplexes and signaled the beginning of our genre’s co-optation by the Hollywood blockbuster machine. Yes, it’s nice to be wanted—but wasn’t yesterday wonderful, when we were happily ensconced in our little shtetls, industriously studying our sacred texts, just us?”

The New York Times’s classical music critic argues that orchestras should end blind audition hiring: “As Tommasini’s piece notes, race- and gender-based discrimination were once commonplace in the hiring process at America’s top orchestras. When two African-American musicians claimed in 1969 that the New York Philharmonic discriminated against them, the controversy forced the Philharmonic and other prestigious classical ensembles to reform the way they hired musicians. From then on, applicants auditioned behind a screen, so as to prevent those in charge from being influenced by their race or gender. The impact of that reform was transformative. Up until then, women and non-white players were a rarity in the ranks of leading orchestras. Now they are commonplace; approximately half of the Philharmonic’s players are female and about 20 percent are Asian. But the number of African Americans remains small. Only one full-time member of the Philharmonic ensemble is black, just as was the case in 1969. As far as Tommasini is concerned, the persistence of that disparity is proof enough that the blind-audition system, which has ensured that a spot in the big leagues of classical music is won solely on merit, should be junked.”

Briefly yesterday, Rod Dreher’s blog at The American Conservative didn’t appear as a result in any Google search. Neither did Prufrock, which is also hosted at TAC. Does Google have a list of conservative websites that at some point it would be willing to block from search results? It seems so.

– – – – –

Did you see this letter to the editor in the New York Times? ‘I never thought I’d turn to The American Conservative for comfort, but at least it has the guts to publish controversial opinions that run counter to conservative orthodoxy.’ TAC is in the midst of its summer campaign—and as a nonprofit, 92% of our revenue comes from donations. Give $250 or more, and we’ll send you a signed copy of Brad Birzer’s In Defense of Andrew Jackson. Support our independent-minded conservatism by donating here.

– – – – –

The substance of style: Cory L. Andrews reviews Farnsworth’s Classical English Style. If you haven’t read any of Ward Farnsworth’s previous guides—Farnsworth’s Classical English Rhetoric and Farnsworth’s Classical English Metaphor—do. They’re quite wonderful.

The White House has removed portraits of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush from the entrance hall.

Photo: Villa Della Porta Bozzolo

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.