Reading in Renaissance England

In the London Review of Books, Irina Dumitrescu writes about reading and language learning in Renaissance England in a review of two books on the subject. The early modern classroom was no safe space. It was loud, multilingual, and bawdy: “Like their Latin analogues in medieval and Renaissance schoolbooks, the sample dialogues in modern language manuals did not shy away from conflict. William Stepney’s Spanish Schoole-master includes a drinking party in which men accuse one another of not imbibing enough. A similar scene in a Latin colloquy written in England six centuries earlier features inebriated monks bullying each other. It seems that textbooks have always recognised the importance of drama and alcohol for language learning.” More:

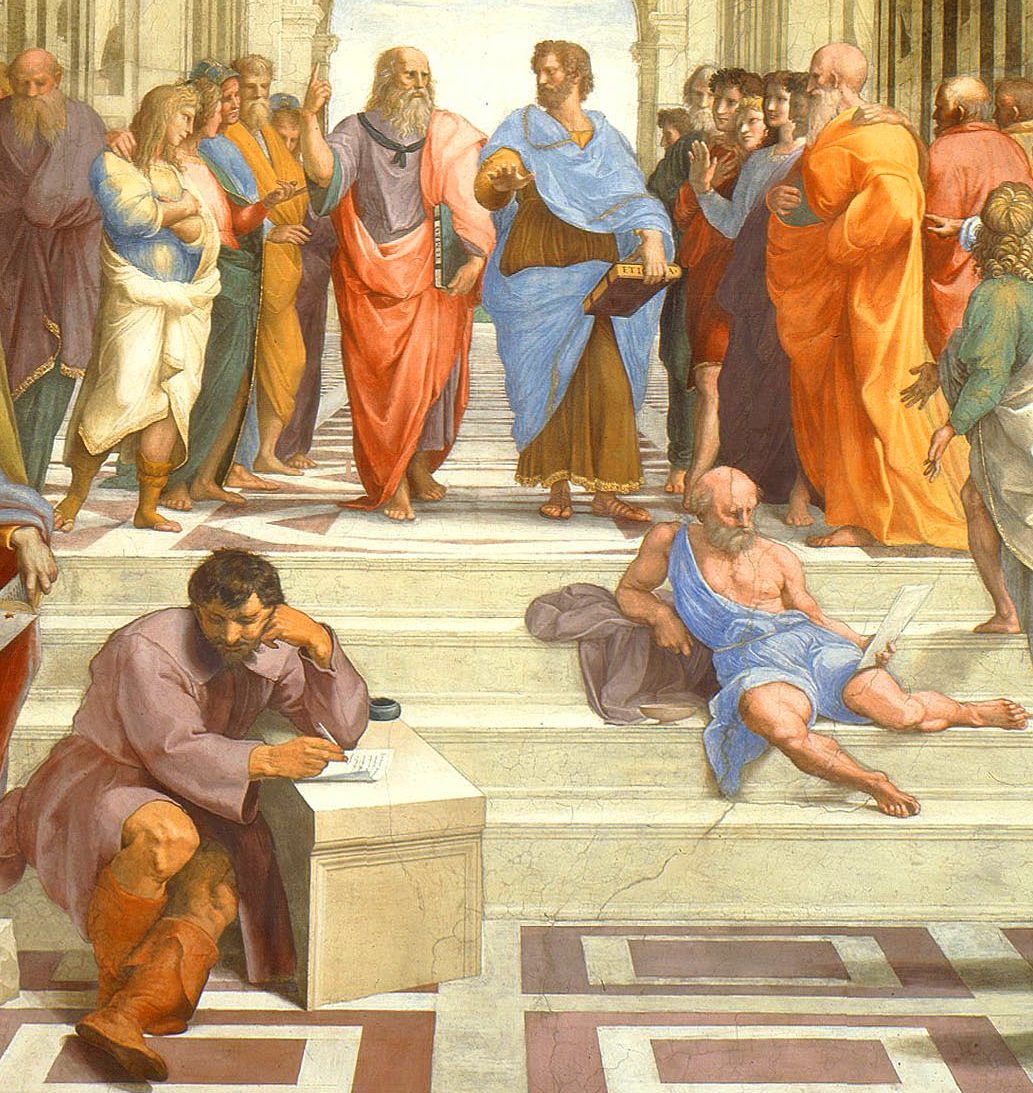

For the bulk of British history, most pupils who had the comparatively rare opportunity of formal education had to become proficient in Latin as a bare minimum. In the British Isles as in the rest of Europe, most instruction in other subjects took place in Latin. From the early Middle Ages into the Renaissance, skill in Latin was a marker of elite status, as it still is, but it was also of practical use for international travel and communication. It was taught using many of the same techniques employed for modern foreign languages today: singing, lively dialogues, reciting poetry, taking dictation and giving speeches. Pupils learned the language orally, in other words, as well as through grammar and the translation of set phrases.

The boys and the few girls who learned to read, write and speak Latin often received an education in drama along the way. The plays of Terence were a mainstay of education in ancient Rome thanks to his exemplary style. Medieval and early modern teachers recognised their pedagogical potential and used individual lines or whole plays as part of their language teaching. That the plays often featured rape, prostitution, extramarital pregnancy and beatings didn’t seem to bother teachers, though some composed Christian works based on Terence’s plays in order to have a cleaner alternative. Even these versions, however, retained some of the provocative elements that made Terence’s dramas so memorable. Dulcitius, a hagiographical play by the tenth-century German canoness Hrotsvit of Gandersheim about three virgin sisters who are menaced by a leering pagan governor, includes a scene in which he is tricked into having sex with some sooty pots and pans. Acting or reading out plays helped pupils connect to a second language. It taught them to deliver Latin speeches clearly and meaningfully. Learning a language was also training in the effective use of voice.

It is easy to overlook how loud premodern education was. Most of our evidence for more than a thousand years of teaching consists of books, and, to the modern way of thinking, books are objects used silently. That this was not the usual way of doing things for much of Western history is now better known, though still difficult fully to understand. In a famous anecdote in the Confessions, Augustine describes seeing Ambrose of Milan reading on his own without making a sound. Ambrose was not the first person in history to read silently, but his quiet, private reading was unusual enough to make an impression. Augustine wondered whether Ambrose did it to preserve his voice or because someone might overhear him reading a difficult passage and ask him to explain it. Scholars have, in turn, asked why Augustine found Ambrose’s silent reading noteworthy: was it simply his ability to do it, or the peculiarity of his solitude? What’s clear is that reading was, for most people, a fundamentally social act.

In other news: I’m sorry to report that Wick Allison, founder of D Magazine, former publisher of National Review, and champion of The American Conservative, has died. He was 72. Rod Dreher remembers him here. Scott McConnell tells the story of how he came to TAC’s rescue.

Lord Leighton’s lesser-known landscapes: “The Victorian art world had its full share of knights – John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Edward Poynter, for example, all received peerages – but the grandest of its grandees, by some distance, was Frederic Leighton (1830-96).”

Ben Smith, the media columnist for The New York Times, published a profile of Andrew Sullivan on Sunday. The title was “I’m Still Reading Andrew Sullivan. But I Can’t Defend Him.” Why can’t Smith defend him? Because Sullivan refuses to apologize for his role in publishing a symposium on Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve . . . in 1994. Sullivan responds: “[T]he media reporter in America’s paper of record said he could not defend a writer because I refused to say something I don’t believe. He said this while arguing that I was ‘one of the most influential journalists of the last three decades’. To be fair to him, he would have had no future at the NYT if he had not called me an indefensible racist. His silence on that would have been as unacceptable to his woke bosses as my refusal to recant. But this is where we now are. A reporter is in fear of being canceled if he doesn’t cancel someone else.”

Working from home has its benefits, Mark P. Mills writes in City Journal, but there are downsides, too: “Forecasters now claim that one of those transformations, aside from demographic and cultural shifts, will be that Work From Anywhere (WFA) becomes customary for huge swaths of the workforce. A recent Harvard Business Review article encapsulated the proposition with a headline question: ‘Is It Time to Let Employees Work from Anywhere?’ Collaterally, others claim that these trends portend a massive decline in transportation fuel use. Pre-Covid, according to Census data, just 5.2 percent of all employees were full-time telecommuters. Note that this is much lower than the 25 percent figure often given for those who say they work from home occasionally. The wildcard in the post-Covid world is how many people convert permanently to WFA. For many, that answer was revealed, and widely cited, in a July 2020 study from the University of Chicago, which found that 37 percent of all U.S. jobs might be amenable, in theory, to remoting . . . We’ll soon see how sticky WFA is once it’s no longer forced. There’s no doubt that it will accelerate the formerly slow-growing trend that began two decades ago and stimulate investments in relevant software and automation as well as changes in corporate behavior. But exactly how many jobs can be done remotely with the same efficacy and productivity?”

Charlie Hebdo reprints its controversial cartoons of Mohammad as accomplices of the 2015 shooting at its offices go to trial.

Dictionary.com changes 15,000 entries to make them more politically correct: “Across the board, Dictionary.com’s language referring to LGBTQIA people has been revised to change ‘homosexual’ to ‘gay’ and ‘homosexuality’ to ‘gay sexual orientation’, with the dictionary saying that the changes would put ‘the focus on people … removing the implication of a medical diagnosis, sickness, or pathology when describing normal human behaviours and ways of being’ . . . ‘This change reflects Dictionary.com’s point of view that language entries have consequences and go beyond being simply an academic exercise,’ it said. Another major revision updates language used around suicide and addiction, with use of the phrase ‘commit suicide’ removed and replaced with ‘die by suicide’ or ‘end one’s life’, while instances of ‘addict’ as a noun are replaced with ‘person addicted to’ or ‘habitual user of’. It said the changes were intended to eliminate language that implied moral judgment or incorporated historical prejudice.”

What should we make of James Tissot today? “The Political Woman was part of a series of 15 paintings of Parisian women that Tissot made on his return to the city after almost a decade in London. Shop girls, circus performers, fashion mavens, artists’ wives, even a female artist and a worn-out art lover in the Louvre announced his return to the painting of modern Parisian life. But French critics kept insisting that the women were English, and British and American collectors were more eager to buy. He was seen by his contemporaries as neither fully French nor legitimately English, but an odd mixture of the two. Americans would end up being his biggest fans. Tissot cultivated the ambiguity about his identity, which contributed to his international success, but also bred suspicion and resentment. The suspicion and resentment have endured. The contemptuous greeting the metropolitan hosts give their awkward provincial guests in Too Early mirrors the reception of Tissot’s paintings over the past 150 years. Critics and scholars tend to dismiss his work as garish and excessive. The French painter and socialite Jacques-Émile Blanche said that Tissot’s pictures were ‘ill-judged for complex reasons’, but some of the reasons are not so complex. ‘More is more’ was his guiding principle.”

Photos: Guizhou

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments