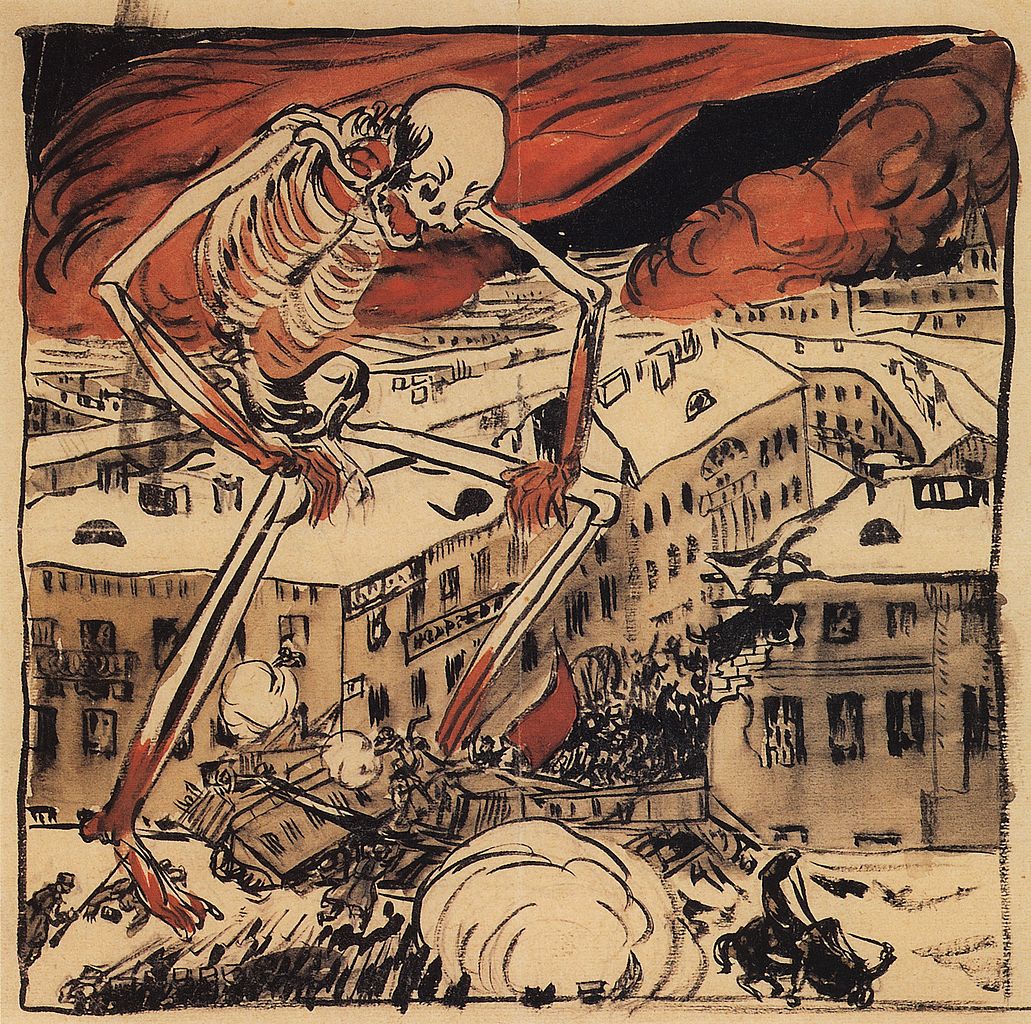

Pre-Revolutionary Russia

What was pre-revolutionary Russia like? A place where robbery, extortion, and murder “became more common than traffic accidents.” Gary Saul Morson explains:

Anyone wearing a uniform was a candidate for a bullet to the head or sulfuric acid to the face. Country estates were burnt down (‘rural illuminations’) and businesses were extorted or blown up. Bombs were tossed at random into railroad carriages, restaurants, and theaters. Far from regretting the death and maiming of innocent bystanders, terrorists boasted of killing as many as possible, either because the victims were likely bourgeois or because any murder helped bring down the old order. A group of anarcho-communists threw bombs laced with nails into a café bustling with two hundred customers in order ‘to see how the foul bourgeois will squirm in death agony.’

Instead of the pendulum’s swinging back—a metaphor of inevitability that excuses people from taking a stand—the killing grew and grew, both in numbers and in cruelty. Sadism replaced simple killing. As Geifman explains, ‘The need to inflict pain was transformed from an abnormal irrational compulsion experienced only by unbalanced personalities into a formally verbalized obligation for all committed revolutionaries.’ One group threw ‘traitors’ into vats of boiling water. Others were still more inventive. Women torturers were especially admired.

How did educated, liberal society respond to such terrorism? What was the position of the Constitutional Democratic (Kadet) Party and its deputies in the Duma (the parliament set up in 1905)? Though Kadets advocated democratic, constitutional procedures, and did not themselves engage in terrorism, they aided the terrorists in any way they could. Kadets collected money for terrorists, turned their homes into safe houses, and called for total amnesty for arrested terrorists who pledged to continue the mayhem. Kadet Party central committee member N. N. Shchepkin declared that the party did not regard terrorists as criminals at all, but as saints and martyrs. The official Kadet paper, Herald of the Party of People’s Freedom, never published an article condemning political assassination. The party leader, Paul Milyukov, declared that ‘all means are now legitimate . . . and all means should be tried.’ When asked to condemn terrorism, another liberal leader in the Duma, Ivan Petrunkevich, famously replied: ‘Condemn terror? That would be the moral death of the party!’

Not just lawyers, teachers, doctors, and engineers, but even industrialists and bank directors raised money for the terrorists. Doing so signaled advanced opinion and good manners. A quote attributed to Lenin—’When we are ready to kill the capitalists, they will sell us the rope’—would have been more accurately rendered as: ‘They will buy us the rope and hire us to use it on them.’ True to their word, when the Bolsheviks gained control, their organ of terror, the Cheka, ‘liquidated’ members of all opposing parties, beginning with the Kadets. Why didn’t the liberals and businessmen see it coming?

In other news: J. K. Rowling’s new book is not “transphobic.” Alison Flood sets the record straight.

Shortlist for Booker Prize hailed as most diverse ever. Hilary Mantel doesn’t make the cut.

Goodreads is terrible. What—if anything—will replace it? “Ten years ago, Tom Critchlow, an independent strategy consultant from the UK (now based in New York), mounted his own challenger to Goodreads: 7books, launched in 2010 and now offline, having peaked at 6,000 users. Since then, Critchlow has been analysing why Goodreads competitors tend not to work. Earlier this year, he published a blog post called ‘A Proposal for a Decentralized Goodreads’. In it, he outlined the fundamental challenges behind creating a serious Goodreads competitor.”

The story of modern Tibet: “A few years ago, I heard a Chinese anthropologist speaking about her work in Tibet. She recalled an incident where she tried to give her Tibetan interlocutors some Chinese apples, until they gently explained that they preferred local fruit, which could be more easily sliced up and distributed to their relatives, typically much more numerous than in ethnic Chinese families. ‘Sometimes’, she explained to us, ‘we need to stop trying to give people our apples and find out why they prefer their own apples.’ This gnomic comment suggested a nuanced understanding of the way that Tibetan lives under Chinese communist rule have been shaped by orders from Beijing rather than by Tibetans themselves. Sadly, such self-awareness is a rarity among the region’s rulers, as Barbara Demick shows in her lucid and poignant account of the tensions that have shaped modern Tibet.”

Erno Rubik, the inventor of the Rubik’s Cube, is still fascinated with his invention. He explains why: “When he invented the cube in 1974, he wasn’t sure it could ever be solved. Mathematicians later calculated that there are 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 ways to arrange the squares, but just one of those combinations is correct. When Rubik finally did it, after weeks of frustration, he was overcome by ‘a great sense of accomplishment and utter relief.’ Looking back, he realizes the new generation of ‘speedcubers’ — Yusheng Du of China set the world record of 3.47 seconds in 2018 — might not be impressed. ‘But, remember,’ Rubik writes in his new book, Cubed, ‘this had never been done before.’ In the nearly five decades since, the Rubik’s Cube has become one of the most enduring, beguiling, maddening and absorbing puzzles ever created.”

Photo: Ostrów Tumski

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.

Comments