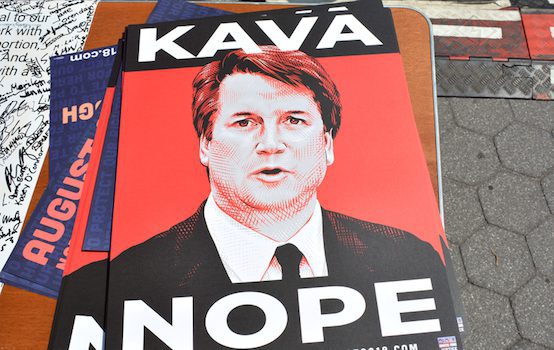

No Kavanaugh: SCOTUS Has Enough Executive Branch Creatures

The United States Supreme Court is packed with executive branch creations. It has been that way for more than 50 years as the nation opted for an empire lead by a Caesar in lieu of a republic fortified and informed by a separation of powers. Judge Brett Kavanaugh would compound rather than diminish the Supreme Court’s troublesome pro-presidential jurisprudence.

An optimal appointee would be Senator Mike Lee (R-Utah). The Senator discerns that the executive branch is everywhere extending the sphere of its activity, and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex. Among other things, the presidency has usurped the congressional power to declare war and the Senate’s power to ratify treaties, killed American citizens without due process, spied on citizens without warrants, invoked state secrets to evade congressional or judicial oversight, and, exercised absolute line-item veto power through counter-constitutional signing statements.

At present, five of the eight sitting Justices are creatures of the executive branch schooled in exalting the president and deprecating Congress: Chief Justice John Roberts and Associate Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Elena Kagan, and Neil Gorsuch. All came to the high court with substantial prior service in executive branch. None had served in Congress, except Justice Thomas who served an abbreviated stint as legislative assistant to Senator John Danforth (R-Mich.) from 1979 to 1981. The justice then served nine years in the executive branch as assistant secretary of education for the office of civil rights and chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Judge Kavanaugh fits the executive branch profiles of these five. Among other things, he served five-and-a-half years in the White House, including three years as Staff Secretary to President George W. Bush. His chief takeaway, as he elaborated in a Minnesota Law Review article, was the conviction that the presidency is vastly more challenging and complex than serving in Congress or the judiciary. Accordingly, presidents should enjoy legal privileges to enable undistracted discharges of constitutional responsibilities.

Judge Kavanaugh insinuates that President Bill Clinton would have devoted more time to capturing Osama bin Laden rather than additional philandering with Monica Lewinsky if he had been relieved of the burden of defending against the Paula Jones litigation and Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr’s derivative investigation of perjury and obstruction of justice. No evidence supports Judge Kavanaugh’s counterintuitive speculation. The Starr Report documents President Clinton’s repeated sexual rendezvous with Lewinsky in the White House chronically distracted him from official duties. President Clinton himself has never maintained that his job performance would have jumped a notch or two if immunity had shielded him from the law. Neither has any other president, including President Richard Nixon, whose Watergate ordeal lasted 18 months until his resignation on August 9, 1974.

Judge Kavanaugh argues the rule of law would be honored if the president could be sued or criminally investigated after departing the White House but not during incumbency. But that could delay justice up to eight years for private plaintiffs during which memories could fade, documents could be lost, witnesses could die or disappear, and plaintiffs could be forced to settle to avoid bankruptcy. Justice delayed is justice denied.

Judge Kavanaugh maintains the impeachment process is an adequate substitute for criminal justice to deter presidential lawlessness. All theory may be for it, but all experience is against it. Impeachment has been employed against only three presidents. In each case, Congress was politically hostile. President Andrew Johnson was impeached by the Radical Reconstruction Congress. President Nixon was taken to the brink of impeachment by a Democratic Congress. And President Clinton was impeached by a Republican Congress. Political partisanship protects presidents from impeachment by Congresses controlled by their own party. And that is when the risk of presidential wrongdoing is at its zenith because of lax congressional oversight. Contrary to Judge Kavanaugh, exposure of the president to civil suits, criminal investigations, or criminal prosecutions are necessary to deter presidential illegalities.

No former member of Congress has sat on the Supreme Court since Justice Hugo Black retired in 1971. He served as a United States Senator from Alabama from 1927-1937 before his appointment by President Franklin Roosevelt. With a congressional background, Justice Black voted to rebuke the President Harry Truman’s seizure of steel mills and President Nixon’s effort to suppress publication of the Pentagon Papers without supporting congressional statutes in Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer and New York Times v. United States, respectively.

Prior congressional service is no guarantee against a justice aggrandizing the executive. Justice George Sutherland had served as United States Senator from Utah prior to his appointment by President Warren G. Harding in 1922. Yet the former senator authored the opinion in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp. that endows the president with limitless power over foreign affairs.

But Sutherland is an aberration. Avoiding executive branch supremacy requires congressional representation on the Supreme Court. Appointing Judge Kavanaugh in lieu of Senator Lee is a missed opportunity.

Bruce Fein was associate deputy attorney general and general counsel of the Federal Communications Commission under President Reagan and counsel to the Joint Congressional Committee on Covert Arms Sales to Iran. He is a partner in the law firm of Fein & DelValle PLLC.

Comments