Jordan Peterson Religious Rohrschach

I posted here over the weekend about Jordan B. Peterson’s appearance at Liberty University’s convocation, and what happened when a disturbed young man rushed the stage. He sobbed, saying that he is “unwell,” and that he needs help. If you go to that link, you can see video of how Peterson and David Nasser, a Liberty administrator and pastor, handled the situation. It was strikingly different. Here’s a link to a clip I had not seen: one that includes smartphone video of Peterson, in the distance, kneeling over the distraught young man and ministering to him while Pastor Nasser leads the crowd in prayer for the sobbing kid:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4CBq47tz77A]

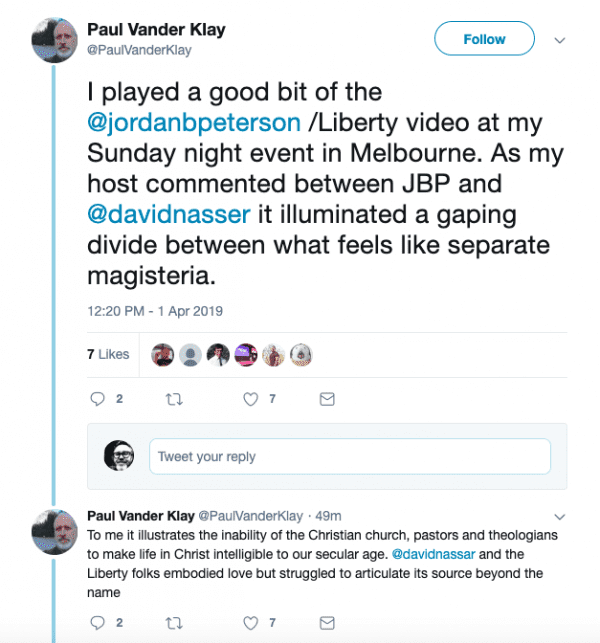

The event at Liberty has prompted a fascinating discussion among Evangelicals about the difference between Nasser’s approach and Peterson’s, and what that says about both Evangelical culture and the challenges of preaching Christianity to a post-Christian world. Here are excerpts from a Twitter thread started by Paul Vander Klay, a Reformed pastor who has engaged with Peterson’s work intensely:

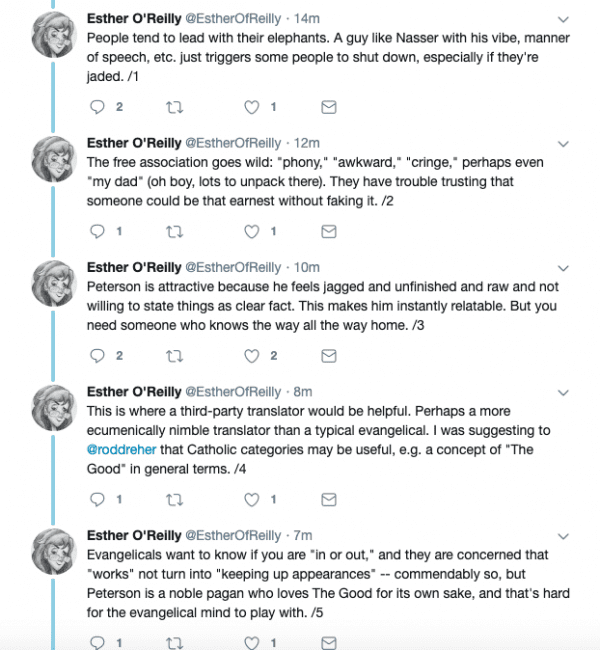

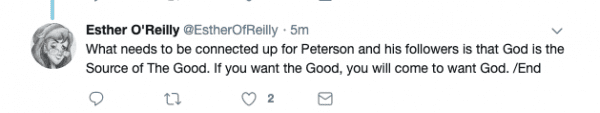

Esther O’Reilly, a teacher and Christian blogger (she’s Protestant, but I’m not sure if she would call herself Evangelical) adds to the thread:

Click here if you want to read the whole thread on Twitter.

Let’s talk about this, shall we? I am a total outsider to Evangelical culture, but I know that the issues they’re talking about here regarding Peterson and Christian ministry are not confined to Evangelicalism alone.

I totally get what O’Reilly says above, about the smooth, therapeutic approach of David Nasser putting people off. I’m a Christian, but I have always been the kind of person who runs far away from that. Yet I know that that’s mostly a matter of personal style. I’m congenitally ironic, and shut down when confronted with religion in its ecstatic, emotionally demonstrative mode. But I am well aware that others relate to God in a different way, and believe me, I’m not judging Evangelicals and charismatics here.

What I’m trying to draw a bead on is why Jordan Peterson can get through to people who have turned their back on the church, or who don’t believe that the church has anything to offer them. I’m inquiring in all sincerity. As regular readers know, I started listening in earnest to Peterson’s Bible lectures last week, and have been startled by how much practical good they have done for me in giving me new ways to think about knotty old problems. I didn’t really expect this. I have been following the Peterson phenomenon from the sidelines, and generally line up with him when he gets in the news for standing up to political correctness. I have smart friends who love him, and I have smart friends who deeply dislike him and what he stands for. I have never learned enough about him personally to take an informed side.

However, based on a few hours of listening to him lecture on the Bible and its psychological importance, it’s becoming clear to me why he has made such an impact. O’Reilly is right above when she describes Peterson as “jagged, unfinished, and raw.” That really is instantly relatable. He also gives you the feeling that he’s still living with a sense of wonder, and that he is also a pilgrim who struggles. It’s still hard for me to put my finger on, because I’ve only listened to about 10 hours of him so far, but he gives the impression that he’s not trying to sell you something. That’s the kind of thing that drives me crazy about a lot of pastors, and their delivery: they come across as trying to sell something. And what they’re trying to sell is analgesic. Peterson seems to be saying: “Life really is hard, life is tragic, but you are called to be a hero despite the pain and difficulty. To hide from that responsibility is to fail yourself. You can do this!”

This is not the Christian message, of course, but it resonates with the Christian message … or at least the Orthodox Christian message. Orthodoxy says that we cannot earn salvation through our works, but it also says that life is a struggle to overcome the passions and yield to transformative grace. I’ve heard it said often that young men in the US are particularly drawn to Orthodoxy because it is serious about struggle, and it calls them out of themselves. I think there’s a lot to this.

I have not watched this conversation between Paul Vander Klay and the Orthodox artist Jonathan Pageau, in which they discuss their mutual friend Jordan Peterson and contemporary Christianity, but my guess is that they talk about such matters. Anyway, I won’t go on any longer about JBP and the church, because again, I’m not really versed in Jordan Peterson Thought™. Love him or hate him, you have to admit that he’s a phenomenon. Peterson means something. I’m not sure what, but I’d love especially to hear from you Christians who have a considered view on why Peterson reaches people that the church has not been able to reach, and how the church’s ministers could learn from Peterson.

Listen, though, if all you have to say are nasty things about Peterson, Evangelicalism, or Christianity, please save yourself the trouble of writing something that I won’t post. I’m too interested in this topic to let the thread get choked off by gripers.

UPDATE: A reader recommends reading this excellent post by theologian Alastair Roberts, reflecting on what pastors can learn from Peterson. Excerpts:

1. People are longing to hear true and weighty words. Peterson is someone who takes truth extremely seriously, treating it as a matter of the deepest existential significance. Telling lies will lead you to perdition. He first came to international attention through his resistance to Canada’s Bill C-16 and his opposition to compelled speech in relation to the pronouns used for transgender persons. What animated Peterson on this issue was not opposition to some supposed transgender agenda so much as the more general principle of truthful and uncoerced speech.

Listening to Peterson speak (the video above being an example), one of the most striking things to observe is how carefully he weighs his words, the way he manifests his core conviction that words matter and that the truth matters. People hang on his words, because they know that he is committed to telling the truth and to speaking words by which a person can live and die. The existential horizons of life and death are foregrounded when someone speaks in such a manner.

We live in a society that is cluttered with airy words, with glib evasions, with facile answers, with bullshitting, with self-serving lies, with obliging falsehoods, and with dishonest and careless construals of the world that merely serve to further our partisan agendas (‘truth’ merely becoming something that allows us to ‘destroy’ or ‘wipe the floor with’ our opponents in the culture). In such a context, a man committed to and burdened with the weight of truth and who speaks accordingly will grab people’s attention.

Here’s another great Roberts observation:

3. People need both compassion and firmness. It is striking how, almost every time that Peterson starts talking about the struggles of young men, he tears up. This recent radio interview is a great example:

Peterson’s deep concern for the well-being of young men is transparently obvious. Where hardly anyone else seems to care for them, and they are constantly pathologized and stifled by the ascendant orthodoxies of the culture, Peterson is drawn out in compassion towards them. He observes that such young men in particular have been starved of compassion, encouragement, and support. There is a hunger there that the Church should be addressing.

However, Peterson’s compassion is not the flaccid empathy that pervades in our culture. He does not render young men a new victimhood class, feeding them a narrative of rights and ressentiment. Rather, he seeks to encourage struggling young people—to give them courage. He tells them that their effort matters; their rising to their full stature is something that the world needs. He helps them to establish their own agency and to find meaning in their labour.

People notice when others care about them and respond to them. However, far too often our empathy has left people weak and has allowed the weakness and dysfunctionality of wounded and stunted people to set the terms for the rest of society. Peterson represents a different approach: the compassionate authority of mature and wise persons can shepherd weak and lost persons towards strength, healthy selfhood, and meaning. Pastors can learn much from this.

OK, one more:

4. People are inspired by courage and a genuine openness to reality. Peterson exemplifies existential struggling with and openness to a real and weighty reality. By contrast, cowardice, acedia, a shrinking back from reality into the safety and comfort of our ideological cocoons, and a preoccupation with shallow theoretical games are largely characteristic of the existential posture of both the society and our churches. You won’t have real experience without courage and openness to a real reality, yet so much of our lives involve childish squabbling and ironic posturing about a reality in which we have little deep personal investment.

Pastors need to display such courage and openness to reality, as these traits beget the experience that will give their words weight. The example of such a pastor will also lead people into true life, rather than just sealing them off from struggling with suffering, sin, questions, and reality more generally. If you lack courage and openness to reality, your teaching will often also serve to close people off from reality, to dull their questioning, to soundproof their lives against the voices that might challenge or unsettle them, to rationalize and facilitate their shrinking from the world. Too many pastors are concerned to reinforce a pen in which they secure their flocks, rather than to protect and minister to them as they undertake their perilous pilgrimage through the vale of shadow.

We should also consider the relationship between preachers and congregations here too. We often lack manly and courageous preachers because we ourselves are so cowardly. We don’t want to be unsettled and challenged. We want messages that are reassuring, comforting, pleasing, and convenient, rather than messages that call us to action, effort, responsibility, or present us with difficulty. There are many with a hunger for courageous engagement with reality and truth and a disgust with people who shrink back from it into palliating falsehoods. Unfortunately, when they look at the Church, they mostly see the latter.

Read the whole thing. It’s all true. Alistair Roberts really knows what he’s talking about.

UPDATE.2: Esther O’Reilly writes:

It seems that a few people in this thread could benefit from the self-reflection invited by Al Plantinga’s savagely convicting “elite’s definition” of a fundamentalist: “a stupid sumbitch somewhere to my ideological right.”

I sit in a liminal space between church traditions, but God forbid I should become an elitist. I offer correction and enhancement where I think evangelical thinking may benefit from it, but I have no time for people who make it their business to make lofty pronouncements about evangelicals. My respect for Mr. Nasser is profound. He is no less genuine than Dr. Peterson, he merely expresses it in a different way. I have no idea what deep meaning people think they can read into the fact that Peterson happened to be the one soothing the student while Nasser prayed. Nasser was also physically calming the student down, was the first to go to him, and visited him in the hospital later when Peterson had left for his next commitment. But people determined to extract something out of nothing are a persistent lot. I should add that Nasser also has a truly astonishing personal testimony, as well as a brother with disabilities. I’ll warrant Dr. Peterson himself left with great respect for the man–more than is being shown here.

Now, to the main thread about why Peterson is having an impact. In no particular order:

1. Peterson’s rough Alberta upbringing combined with his academic background is a unique combination. It makes him at once intellectually formidable and iconoclastic: an academic who frequently gets impatient with other academics and is only interested in communicating knowledge that might be useful to someone. The academy can’t stop him, and the laymen can’t not love him.

2. Peterson’s evolutionary synthesis of science and religion gives people the illusion of reconnecting worlds. I say “illusion,” because I maintain that evolutionary reasoning lacks the explanatory power to account for even biological reality, let alone harder problems like consciousness. But Darwin won the PR campaign, if not the argument, and Peterson is a product of that. The evangelical response has historically been disastrously splintered, mostly into a stubbornly holistic Young Earth Creationism on the right and a full capitulation to the evolutionary paradigm on the left (often accompanied by sanctimonious beat-downs of “creationists” of any stripe). Whole books could be written on what this has done to the Church.

3. Peterson has no script. He is improvising as he goes along, which makes people feel like they are along for an adventure. By contrast, ministers are constrained by their job and social position to create an atmosphere with little room for spontaneity. They need to write sermons ahead of time, make lesson plans ahead of time, etc. And they need to stay within whatever set bounds their particular denomination has set for them, be it Catholic, Protestant, or Orthodox. Freedom to go off-script is severely limited.

4. Peterson exemplifies a full-bodied range of masculine emotions without ever seeming contrived. Whether he’s exhorting someone, being angry, or weeping, all of it seems to flow organically from a different part of himself that’s authentically him. This is not to disparage men who struggle to access their emotions in this same authentic way, or men who have been trained in a style that rubs the rough edges smooth. It just is what it is. However, it is definitely a sad comment both on pastors who disdain authoritative masculinity and on pastors who reduce masculinity to an exercise in chest-thumping. Peterson steers the middle course.

5. Peterson is an unexpected shock to the system for rebellious young people who will shrug off a pastor or a parent. He’s like the schoolteacher or the coach who comes in and gives that assist when the exhausted parent is at her wit’s end. One young man wrote me that after a stint as an angry Internet atheist, Peterson’s exposition of Cain and Abel cut him to the quick, because he saw himself in Cain. He suddenly understood, viscerally, that as Peterson says, you can’t twist the fabric of reality without having it snap back.

6. Peterson understands human nature, including all the dark corners thereof where people often fear to tread–humiliating mental illness, family dysfunction, depression, senseless tragedy. By contrast, some pastors can be too quick to move on from lament. Peterson can teach us something about grieving, even as we could teach him something about rejoicing.

That’s all I got for now.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.