Graham Pardun’s ‘The Sunlilies’

Most of you know that I write a subscriber-only Substack newsletter, Rod Dreher’s Diary, that I use to focus on positive, hopeful topics, usually having to do with faith and spirituality. Sometimes I repost material from it to this blog, when I think it’s something of real interest. Below is a version of something I posted yesterday. A Catholic friend put me on to a new, self-published Orthodox Christian writer in Minnesota, a young man named Graham Pardun. My Catholic pal said Graham’s thin little book of essays is solid gold. I bought it, and agree wholeheartedly. More people should know this young writer and his work. Here’s a slightly edited version of what I sent to my Substack readers yesterday.

Let me tell you about an extraordinary little book of essays recommended to me by a Catholic friend: The Sunlilies, by Graham Pardun. The author is an Orthodox Christian living in Sandstone, Minnesota. He self-published the book, and sells it through Treedweller.net, his website (there’s something buggy about that site; if it won’t load the first time, reload it, and all will be well). I bought a hard copy yesterday, but persuaded Graham to send me an electronic copy so I could read it at once, and tell you all about it. I’m so glad he did! From the preface:

I’m nobody special, though—just a man of my times, like anybody else. Therefore, I wish to conclude this preface not with my own new words, but the new words of someone else, whose words express my heart completely—Paul Kingsnorth, from his essay, “The Cross and the Machine,” an account of his long conversion to Orthodoxy:

In the Kingdom of Man, the seas are ribboned with plastic, the forests are burning, the cities bulge with billionaires and tented camps, and still we kneel before the idol of the great god Economy as it grows and grows like a cancer cell. And what if this ancient faith is not an obstacle after all, but a way through? As we see the consequences of eating the forbidden fruit, of choosing power over humility, separation over communion, the stakes become clearer every day. Surrender or rebellion; sacrifice or conquest; death of the self or triumph of the will; the Cross or the machine. We have always been offered the same choice. The gate is strait and the way is narrow and maybe we will always fail to walk it. But is there any other road that leads home?

What is this book of essays about? Says Graham:

This is a book about Orthodoxy being a challenge to our culture’s pervasive nihilism by being “radical,” in the sense of getting back to our roots. I mean this in two ways: A return to the ancient path of Yeshua Messiah, the root of all human flourishing, and, secondly, a return to the human body and its simple, but deep connections with the garden of Eden.

For me, the image of a lily fluttering in the sunshine encapsulates both: On the one hand, Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow is at the heart of Yeshua’s teaching and way of life, as relayed above; on the other, the earthy, ephemeral beauty of the flower is a primary biblical image for the earthy, ephemeral beauty of the human person, rooted in Creation: “As for man, his days are like grass—he flourishes like a flower of the field” (Ps. 103:15)—and, also, when God comes to Earth as a healing dew, the Children of Israel will “blossom like a lily” (Hos. 14:6). In what follows, I would like to describe this flowering of Sabbath life under three aspects: wakefulness, surrender, and unity of breath. Taken as attitudes, these are three aspects of love, which is a form of attention and participation. Taken as practices, they’re just a childlike form of “irreligion,” the Orthodoxy of the flowers and the birds.

There is not enough space in this newsletter to quote at length from the richness of this little book, and Graham Pardun’s religious imagination. If you like Paul Kingsnorth’s writing, you will love this book. You want to know how to experience the world as “re-enchanted,” that is to say, as hallowed? Graham Pardun tells you. The only writer who makes me feel this way about God and Creation is the great twentieth century rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, and sometimes Wendell Berry. Here, in this rapturous passage filled with wonder, is Graham Pardun reflecting on the tension between the Mosaic prohibition on “graven images,” and the fact that God told the ancient Hebrews to make images of the cherubim (here, cheruvim) in the Temple:

And now, to the Inmost Sanctuary, in which the Ark resides—the “Holy of Holies”—which will carry us the rest of the way to the edge of the Hebraic universe: That there is an Inmost Sanctuary within the main Sanctuary, within the city-like Temple, within the Temple-like Earth, in which mountains, rivers, trees, and even stars sing songs of praise, according to the book of Psalms, shows that the usual dichotomy anthropologists and sociologists make between “sacred” and “profane” space doesn’t quite fit here; for the Hebrews, there is only sacred space, and even more sacred space:

The heavens are yours —Also yours the Earth

The world and all its fullness… (Ps. 89:12)

— thus, for the Hebrews, the highest stars are holy, and, below them, the bright planets are holy, too (and, below them, the yellow sun and silver moon— all holy, all full of the beauty of ADONAI), and below the sun and moon and stars, the soaring white clouds are holy, and, below them, the soaring birds of the air are holy, and, below them, the butterflies and dragonflies—all flying insects that flutter in the sky, all of them are holy—and below them, the shining green trees of Earth, and then the lilies of the field beneath them—all holy, holy, holy—and the blue rim of the sky is holy as well, and the sparkling blue seas from horizon to horizon are holy as well, and the red clay and brown earth and yellow sands of Earth are holy as well, and the Holy Land of Israel at the center of Earth is holy, holy, holy as well, and the Holy City, Jerusalem, at the center of the Holy Land is holy as well, full to the brim with the beauty of ADONAI, and the holy Temple, a most holy city within the Holy City, is holy, and the sanctuary within the holiest city is holy, and the Holy of Holies within in the sanctuary is holy—and when the High Priest walks in and prostrates his precious human body to the ground on the most holy day of the year, this completes the whole holy cosmos, as the Hebrews saw it: concentric circles of holy images of God, like flower petals converging on the human heart.

It is within this context that we can say what Orthodox iconography is: It is the lyrical cheruvim of the ancient Temple, but one radical step further: A beautiful, childlike “idolatry” which reveals the true image of God not as emptiness as such, but as the precious human body. And it is in this sense primarily that we can become the “priesthood of all believers” in Messiah: Every deified saint we see on an Orthodox icon is standing, as it were, in the Holy of Holies, not just once a year, but eternally Now, offering praise to the Father of All out of the fountain of his or her own precious human heart.

My longtime readers know that I struggle to find God’s presence in the natural world. My theory is that having grown up in south Louisiana, where the natural world is (to me) unpleasant — hot, humid, full of mosquitoes and poisonous snakes — I have an aversion to it. In the past I have written about being struck hard by the glory of God in certain natural places — in the Japanese cedar forests of the Azores, for example. And in a cave there. I wrote about visiting this cave on the island of Terceira in 2018. Here’s the view from midway to the bottom:

I was filled with religious awe there, but then:

I was shaken out of my reverie by the chatter of the tour group that had settled in around me. They would not shut up. They were mostly older people, and had no respect for their surroundings. How could you be in a place like this ancient cavern and natter on like you were standing in line at the food court at the mall? I tried to block them out, but their chatter grew louder in the echo of the cavern.

Honestly, I’m embarrassed to think about how angry I was in that moment, but thinking about the source of that anger explains a lot to me about myself. All of us were in the presence of something holy, something that, if we were properly disposed internally, would have evoked an experience of awe, of silence. Kingsnorth is not a religious believer, but he gets it [Note: I had quoted from Paul Kingsnorth’s 2014 essay “In The Black Chamber,” about a cave; Paul is now an Orthodox Christian — RD]. Every one of those older people jawing around me might be churchgoers who are more morally upright than I am, but they did not get it. To them, this cavern was just something else to be consumed.

The modern world simply does not know when to shut up. It does not know how to behave in the presence of the sacred. This scorn and indifference towards the sacred, in the presence of the eternal, is what I find so difficult to bear about the contemporary world. It is why I imagine that I would have a greater kinship with an atheist like Paul Kingsnorth than I would with conservative Christians who don’t know how and when to shut up.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but emerging from the cave, I was a changed person. It wasn’t just the cave, but also the Japanese cedars I had encountered earlier that week on the island of Sao Miguel:

I can’t say that I’ve ever felt such a strong bond with nature before this trip. I’m not sure why that is, though my wife says, reasonably, “Because nature here is not trying to kill you.” This is a reference to the venomous snakes in Louisiana. There are no snakes in the Azores. Not having to worry about poisonous snakes — one of my greatest fears — caused me to let my guard down in the presence of nature. It was marvelous, literally: a marvel. If I had the chance, I would take a sack of books, an icon, my prayer rope, some wine and sausage and cheese, and camp out for some days in a grove of Japanese cedars. I can’t explain this feeling. Maybe it’s the latent Entishness within me. Those groves felt sacred in ways that I cannot explain, but definitely discerned.

On the flight back to the US the next day, I dreamed of the cavern, and woke up thinking about it. The cavern represents contemplation, and a descent into the unconscious. My patron saint, Benedict of Nursia, lived in a cave, praying and fasting and seeking God, before emerging to take up his ministry. What’s wrong with us is that we don’t know how to descend into the cave, so to speak. We don’t know how to be silent in the grove. Even when we go into the cavern, we want to take the outside world with us (if there had been a signal near the cavern’s core, I probably would have tweeted the photos), so that we are never truly alone with our thoughts and our God.

The rebirth and restoration that so many of us long for will not happen until and unless we journey into the cave of contemplation.

Now, with that passage from my past writing in mind, read this from Graham Pardun, who, by his words, is teaching me how to re-orient myself to the Lord God manifesting Himself in Creation:

So, whereas to be the children of God is to experience the restoration of nature’s abundance (“I will pour water on the thirsty land”) and also ourselves as willow trees springing up in the grass by flowing streams of water, to be idolaters is the reverse of that: Taking trees planted by God, which have grown “strong among the trees of the forest,” nourished by God’s rain and sunshine, we cut them down and reshape them according to our darkened imaginations—and we also burn them to keep warm, roast animal flesh, and also to bake bread—but since we don’t give thanks to the Source of all who made trees, fire, animals, wheat, yeast, and salt, but instead bow down to the gods of our own minds, in the end, all we eat is ashes—and therefore all we become is ashes, too.

Compare the aliveness of a tamarack tree—its golden needles in the fall, its fragrant cones and bark, the blue sky shining between the needles, the chickadees leaping from branch to branch, all one totality praising the name of God—compare that to a statue carved out of wood: There is no comparison, really. No matter how skillfully carved, the wood statue, next to the living tree, is junk—a piece of cultural driftwood—just a mirror, the human mind talking to itself about transcendence. That we feel we must make, and then bow down to, such images of ourselves, reveals a profoundly debilitating interior captivity.

I think of the practice in ancient Sumeria of worshipers fashioning clay avatars of themselves, and placing them, eternally wide-eyed, in circles around their images of the gods in the center of their temples. This was so that they—truly present in, and as, their avatars, since the priests would breathe the breath of life into these likenesses of clay, ritually completing the identification—could ceaselessly attend their gods, without having to eat, drink, plant, water, harvest, sleep, take care of children, et cetera—since these gods, as nothing more than the magnified human ego, demanded perpetual worship. In a way, this was an ingenious solution to a self-imposed problem; in another way, though, how sad that the tension between the unbearable psychic burden of religion on the one hand, and the vital forces of nature on the other, ended in temples of stone cluttered with artificial people staring catatonically at their own artificial gods.

This is the bleak religious background against which the Hebrew vision appears as a radical, life-affirming iconoclasm:

God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them. (Gen 1:27)

And then once more:

Now no shrub of the field was in the land yet, and no green plants of the field had sprouted yet….Then ADONAI Elohim formed the man out of the dust of the ground and he breathed into his nostrils a breath of life—so the man became a living being. Then ADONAI Elohim planted a garden in the east, and there he put the man whom he had formed. Then ADONAI Elohim caused to sprout from the ground every tree that was desirable to look at and good for food… (Gen. 2:5,7-9)

This is ancient Near Eastern religion flipped on its head, blown apart by the Hebraic revelation: Instead of people fashioning clay images of themselves, breathing into their clay nostrils, and placing them in temples of stone, to stare lifelessly at lifeless images of the gods, the Living God fashions living images of himself from Earth and places them in a garden, which, as these living images of God themselves come alive in the breath of God, itself comes alive, and vice versa, such that both experience a reciprocal blossoming. This godlike mutualism between Earth and man, is, for the ancient Hebrews, what it is to be truly alive—to have eyes that really can see God, who is everywhere, embodying himself in all things, and to have ears that really can hear God, whose voice is in the song of all songbirds and in all lilies fluttering in the wind.

Thus, sacred space in the Hebraic vision of life is first of all not a temple of stone, but Eden, a Living Garden planted by the hand of God. And thus, the calling of mankind as the kings and priests of God is first of all not the construction of stone temples and the orchestration of liturgies within them, but care for the wild things of Earth and the celebration of the Cosmic Liturgy with the birds and clouds and stars, and the walia ibexes and leaping dolphins.

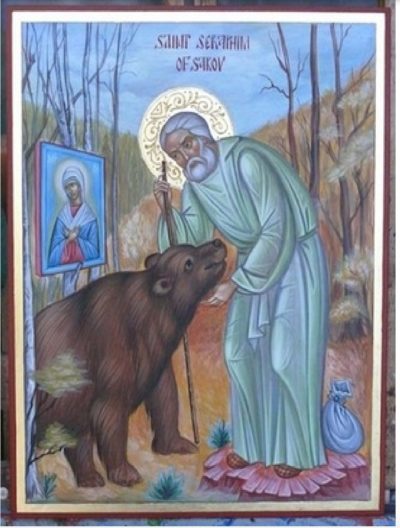

This is a vision of life which Orthodoxy shares (and even vastly expands, in light of the Risen Messiah)— as expressed, for example, in icons like this:

Here, Saint Seraphim [who befriended a bear, Misha — RD] lacks nothing, dwelling in the Sabbath rest of Eden, a lily-like priest and king of Creation: The floor of the Temple in which he sings psalms to the Creator is the rock he’s standing on—its walls are the birch trees; its roof, the sky.

At the same time, what makes it possible to see this icon as giving an Orthodox theology of sacred space as such is that there is, within the icon—as if in an infinity mirror—an icon of Mary perched on a tree, and it is to her that Saint Seraphim has turned his body. So Seraphim really is standing to pray in an Orthodox temple as such, as delineated by the presence of a holy icon; but, at the same time, he himself is an Orthodox temple, glorifying God from the inmost sanctuary of the heart (which is why his face radiates the shekinah of God—the luminous presence of ADONAI which used to fill the Holy of Holies in the ancient Temple of wood and stone). Moreover, he is also aligning his temple-body with an image of the Temple of God, Mary’s precious human body, the body in which God’s long process of self-embodiment in nature climaxed in the miraculous conception of Yeshua Messiah—who said his own body would become the true Temple when it rose from the dead, which it did (cf. Jn. 2:19-22).

Now let’s imagine we place a copy of this icon of Saint Seraphim in the branches of our own birch tree, facing East, and let’s imagine, as we chant a few psalms with our lips, silence, like a Living Fountain, begins to flow from the depths of our own hearts and pervade everything, and our chanting gives way to the ineffable psalms of the heart, and the voices of the songbirds in the trees become, for us, the voice of God, singing psalms, and the breath of wind on our faces becomes, for us, undeniably the presence of the Living God—his Sabbath rest: This a glimpse of what the whole universe is like everywhere all the time, as [Philip] Sherrard said for us at the top of the essay:

In some sense, the image is the archetype in another mode, and only differs from the archetype because the conditions in which it is manifested impose on it a different form. Essentially, therefore, the principle is one of transformation of inner into outer, of an interlocking scale of modalities in which the same basic theme is repeated…It is this structure of participation which constitutes the great golden chain of being…[In it] there is nothing that is not animate, nothing that is mere dead matter…Each thing is the revelation of the indwelling creative spirit.

In our example here in the forest with the birch trees, Yeshua, the Son of God, is the archetype—the True Temple, the One for the sake of whom the universe was created so that God could rest in him. The universe itself, as the self-embodiment and self revelation of God, is an image of that archetype—it is that archetype, shaped by a different set of conditions, and therefore realized in a different form. Thus, “the whole universe is God’s Temple,” too—and also the Body of Yeshua, who fills all things (cf. Col. 1:15-20).

Likewise, the garden-Temple of Eden, the stone and wood Temple of the Hebrews, and the living Temple of Mary’s body—all realizations of the One, each one blossoming forth under circumstances appropriate to itself—likewise, the holy image of Mary and the little forest-Temple of trees and stone it creates for Saint Seraphim, and likewise, Saint Seraphim himself, and our own precious human bodies, too, if the Inmost Sanctuary of our hearts are open to the living, breathing cosmos of God shining forth from Seraphim’s icon: all of these images, daisychained to one another by mutual participation, are transformations of the inner life of God into the outer life of all things.

Thus, what begins as a juxtaposition between “dead” and “living” images of God (wooden idols versus trees, clay avatars versus the real human body) seems to have ended in the transcendence of any such distinctions: All things—from the smallest fleck of blue paint in the dimmest icon to the largest blue whale singing in the deepest, bluest ocean, are living images of the living God—or they can be, anyway: Perhaps better to say that for the living, all things are living images of the living God, whether stones or dolphins, forests or icons—but for the dead, everything in the universe is only so much raw material to be cut down, carved, and burned. This is the lyricism of the Hebrew mind fleshed out by Orthodox theologians with the help of Platonic philosophy; to try to collapse it through logic results only in a tonedeaf idolatry… .

I have to stop there, because I am reaching the limit of length in this newsletter, but more than that, I want to go pray. What a discovery is Graham Pardun’s work! I am laboring on a big book that, if successful, will help people to achieve the vision that Graham Pardun already lives. And I’ve only been quoting from the first essay — there is more to go, and I am so excited to read it. You have to buy this book! I know that this is a book I’m going to buy many times as gifts.

It is speaking to me not only as a man researching re-enchantment (which is to say, re-sacralizing the world; which is to say, re-learning to see what is already there), but also as a sinner struggling to break free of his own head. You regular readers know all too well that I saw myself in this dream sequence from Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia:

Present in the holy world, but not able to perceive its holiness, because I, like Andrei, am so locked in my head. In Andrei’s case, it was because he obsessively longed for his homeland. In my case (I can now reveal, in light of the divorce petition my wife filed), it was obsessive longing for the happy marriage I used to have, but could not recover now matter how hard I tried … and could not stop thinking about, trying to figure out new ways back to that blessed land from which I had been exiled.

I did not choose this divorce, but now that it has come upon me, may God help me redeem all the brokenness by opening my eyes to His world, as it is, and becoming a source of light, not darkness. I’m grateful to have discovered, with the help of my Catholic friend, the vision of Graham Pardun. I expect that my next newsletter will contain more reflections on his short but powerful essays. Reading Graham Pardun, I feel that I’m encountering the Orthodox Christian son of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Wendell Berry.

Again: buy The Sunlilies! And once you have read it, tell everybody you know about it. I know I am.

—

One more thing I want to add: thank you all again for your kind words and prayers regarding the divorce. Please do remember me, my wife, and our children in your prayers. I want to emphasize here that my wife is a good woman, and I bear her no anger or malice. These late nine or ten years have been very hard on both of us, and I am grateful that we have both been given by God the grace to settle this amicably. Some unkind people have said to me that if we were serious Christians, we wouldn’t be divorcing. The truth is that if we were not serious Christians, we would have ended the marriage years ago, instead of struggling with all our might to save it.

Life is long and difficult. Take nothing for granted, friends. As I never tire of telling all fellow Christians, when I was a Catholic, I literally never imagined that I would lose my Catholic faith … yet it happened. I thought I could control it, but the forces that engulfed me in all that tore my Catholicism away from me. If I had been a stronger person, or at least a different person, things might have turned out differently. Similarly with divorce. I thought divorce was something that happened to other people, not good, right-believing, conservative Christians like us. Obviously I’m not going to talk about the circumstances leading up to this sad fate, other than to say, as my wife and I did when we announced the divorce, that infidelity was not an issue — but I am going to caution all of you readers, married and unmarried, never to assume anything about the stability of human endeavor. We are all living out the consequences of the Fall. Man hands on misery to man… . Sometimes all we can do is, like Jesus in Gethsemane, put down our swords (as He ordered Peter to do), and walk bravely to our fate.

It is only by the grace of God that I find myself in a good and serene place in the face of this trauma, and I think the same is true for my wife. One thing I have learned between the loss of my Catholicism in 2005 and the loss of my marriage this year is to trust not in my own power to control things, but rather to trust so much more in God, and in His goodness, and in His presence with us through suffering. To be faithful is not to be an optimist, but to be hopeful. Christian hope tells us that no tragedy, no matter how horrible, can conquer us if we walk in the passion of the Christ. That is a real thing. It is the realest thing there is. I look down every day, often, at the mark I had placed on my skin in Jerusalem, on Holy Week, by Wassim Razzouk, and am reminded that JESUS CHRIST CONQUERS (which is the meaning of this medieval Greek symbol).

Sorry to get all super-Christian on you — I usually keep that kind of thing to Rod Dreher’s Diary (subscribe!) — but I believe IC XC NIKA with all my heart, and it is the only thing keeping me going right now.

Anyway, this isn’t a post about me. It’s a post about the extraordinary Graham Pardun, about whom we will all be hearing a lot more in the future, I am certain.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.