Politics, Family, & the Benedict Option

Ross Douthat had a column yesterday talking about how the decline of the family brought us to this particular miserable place in the presidential election. Excerpts:

How did we get here? How did it come to this? Not just to the Donald Trump phenomenon, but to the whole choice facing us on Tuesday, in which a managerial liberalism and an authoritarian nationalism — two visions of the president as essentially a Great Protector: a feisty grandmother or fierce sky father — are contending for the votes of an ostensibly free people?

Start with the American family. Start with my own family, as an illustration — white Protestants for the most part on both sides with a few Irish newcomers mixed, rising and falling and migrating around in the way of most families that have been in this country a long time.

His was a big family, until:

Then the social revolutions of the 1970s arrived. There were divorces, later marriages, single parenthood, abortions. In the end all those aunts and uncles, their various spouses and my parents — 12 baby boomers, all told — only had seven children: myself, my sister and five cousins.

So instead of widening, my family tree tapered, its branches thinned. And it may thin again, since so far the seven cousins in my generation have only three children. All of them are mine.

The column ends like this:

In either case, the demagogues of the future will have ample opportunity to exploit the deep loneliness that a post-familial society threatens to create.

This loneliness may manifest in economic anxiety on the surface, in racial and cultural anxiety just underneath. But at bottom it’s more primal still: A fear of a world in which no one is bound by kinship to take care of you, and where you can go down into death leaving little or nothing of yourself behind.

There was some online reaction yesterday along the lines of “sheesh, get a load of that right-wing Catholic rant about the evils of contraception.” That is completely misguided. Douthat’s point is profound. It’s about the loss of community and communal purpose, and the effect this has on our politics. It’s not just about America, either.

Douthat wrote the introductory essay to ISI’s 2010 reprint of Robert Nisbet’s classic 1950s study The Quest for Community. In that intro, Douthat described the book “not as a policy manifesto for a movement or a party, but as a thoughtful, elegant, and persuasive statement about human nature, and the kind of politics that’s best suited to the cultivation of our common life.”

Nisbet’s book is due for a re-reading. Consider these passages in light of the choice the nation faces tomorrow. The first lines:

One may paraphrase the famous words of Karl Marx and say that a specter is haunting the modern mind, the specter of insecurity. Surely the outstanding characteristic of contemporary thought on man and society is the preoccupation with personal alienation and cultural disintegration.

Nisbet wrote those lines in 1953. This didn’t just happen to us yesterday.

Modernity, he writes, is about the steady emancipation of the individual from the dead hand of the past. We have achieved this to an extraordinary degree, but we have found ourselves surrounded “by the sense of disenchantment and alienation.”

Mary Eberstadt wrote a good book a few years ago putting forth the theory that the West lost God because it first lost the family. This idea shows up in Nisbet, who says that when our relationship to God is not mediated through “the concreted facts of historical life,” then “the relation with God becomes tenuous, amorphous, and insupportable.

For more and more theologians of today the solitary individuals before God has his inevitable future in Jung’s “modern man in search of a soul.” Man’s alienation from man must lead in time to man’s alienation from God. The loss of the sense of visible community in Christ will be followed by the loss of the sense of the invisible. The decline of community in the modern world has as its inevitable religious consequence the creation of masses of helpless, bewildered individuals who are unable to find solace in Christianity regarded merely as creed. The stress upon the individual, at the expense of the churchly community, has led remorselessly to the isolation of the individuals, to the shattering of the man-God relationship, and to the atomization of personality.

Check this out, keeping the Trump voter in mind:

Material improvement that is unaccompanied by a sense of personal belonging may actually intensify social dislocation and personal frustration.

“The true hallmark of the proletarian,” Toynbee warns us, “is neither poverty nor humble birth, but a consciousness — and the resentment which this consciousness inspires — of being disinherited from his ancestral place in society and being unwanted in a community which is his rightful home; and this subjective proletarianism is not incompatible with the possession of material assets.”

Here’s something else:

For an ever-increasing number of people the conditions now prevailing in Western society would appear to have a great deal in common with the unforgettable picture Sir Samuel Dill has given us of the last centuries of the Roman Empire: of enlarging masses of individuals detached from any sense of community, status, or function, turning with a kind of organized desperation to exotic escapes, to every sort of spokesman for salvation on earth, and to ready-made techniques of relief from nervous exhaustion. In our own time we are confronted by the spectacle of innumerable individuals seeking escape from the very processes of individualism and impersonality which the nineteenth-century rationalist haled as the very condition of progress.

I’ll quote one more bit before moving on:

Why has the quest for community become the dominant social tendency of the twentieth century? What are the forces that have conspired, at the very peak of three centuries of economic and political advancement, to make the problem of community more urgent in the minds of men than it has been since the last days of the Roman Empire?

It has been some time since I read this book (I am pulling quotes from my own marked-up copy; the ones you see here are among the many I underlined), but I recall that the most dated part of the book is Nisbet’s assumption — common among 1950s conservatives — that the Leviathan State was the chief enemy of true community. What Nisbet did not anticipate was that unrestrained market capitalism was also an enemy of same. I thought this Thomas Frank essay yesterday in The Guardian bashing both Republicans and Democrats for failing blue-collar America was half-brilliant, in the way Thomas Frank is. Excerpts:

But what makes Trump the ace is that he has successfully captured the anger of average people who see themselves on the receiving end of a “rigged” system, to use the cliche of the year. He has turned the tables of class grievance on the Democratic party, the traditional organisation of the American left. How did this happen?

Let us start with the Democrats. Were you to draw a Venn diagram of the three groups whose interaction defines the modern-day Democratic party – liberals, meritocrats and plutocrats – the space where they intersect would be an island seven miles off the coast of Massachusetts called Martha’s Vineyard.

It is, says Frank, the habitat of wealthy technocratic liberals who think of themselves as representing the underdog. But they’re wrong. Here’s more, with Frank quoting a union activist:

“And they understand,” he continued, “that they’re working two and three jobs just to get by, a lot of them can’t own anything and they understand seeing Mom and Dad forced into retirement or forced out of their job, now they’re working at Hardee’s or McDonald’s to make ends meet so they can retire in poverty. People understand that. They see that.”

Those awful words are a fairly accurate account of the situation faced by a vast part of the population in America, a population that was brought up expecting to enjoy life in what it is often told is the richest country in the world. It is not really the fault of Barack Obama or Bill Clinton that things have unfolded in such a lousy way for these people. As everyone knows, it is the Republicans that ushered the world into the neoliberal age; that cut the taxes of the rich with a kind of religious conviction; that did so much to unleash Wall Street and deregulate everything else; that declared eternal war on the welfare state.

And, as usual, here is where Frank skews things. You can certainly blame Bill Clinton for things going wrong, as well as the Republicans. That’s the whole Clinton thing: Democrats who have made their peace with free market economics. Anybody who thinks the economic cock-up was entirely a Republican plot ought to spend some time watching the PBS Frontline documentary about Brooksley Born. I don’t think it’s available to watch online anymore, but you can certainly read transcripts of the interviews. Here’s a clip from the interview with Born’s colleague Michael Greenberger, explaining why Alan Greenspan, Bob Rubin, and the Clintonistas shut her down in 1998 when she warned them that the big banks were out of control:

But at that time, why do the banks have such clout inside the Clinton administration?

It’s a very interesting question. But I think one of the driving forces, politically at that time, was that the financial services industry was essentially a Republican-captured institution and that these were the New Democrats that were going to prove to the financial services industry that they could do better. The economy is booming. You’ve never made so much money. Don’t look to the Republicans as your saving grace. Look to the Bob Rubins of this world, who are melding Democratic politics with a growth economy. …

Trump is right about this: when it comes to Wall Street and big money, there is only one party in Washington. If you expect Clinton Democrats to be better than Republicans, you’re fooling yourself.

Anyway, back to Thomas Frank:

But history works in strange ways. Another thing the Republicans did, beginning in the late 60s, was to present themselves as the party of ordinary, unaffected people, of what Richard Nixon (and now Donald Trump) called the “silent majority”. They cast the war between right and left as a kind of inverted class struggle, in which humble, hard-working, God-fearing citizens would choose to align themselves with the party of Herbert Hoover.

And so Republicans smashed unions and cut the taxes of the rich even as they praised blue-collar citizens for their patriotism and their “family values”. Working-class “Reagan Democrats” left their party to back a man who performed enormous favours for the wealthy and who did more than anyone to usher the world into its modern course of accelerating inequality.

What drives me nuts about Frank’s analysis (and this is what he always says) is how materialist it is. He doesn’t seem to understand that these moral and social issues that Democrats like Frank simply don’t take seriously actually are taken seriously by many Republican voters. Look, if you were an economically liberal gay voter, and for whatever reason the GOP was much better than your own party on gay rights, wouldn’t you vote Republican, or at least be seriously tempted to? You would do so because there are some issues that are more important than economics. Frank’s take on things is that if Reagan Democrat types had only realized that social issues were truly meaningless, nothing but an attempt to distract them from what really matters, the distribution of resources, they would have voted Democrat all along. This is as blind as conservative stalwarts who cannot or will not see that the economy really does play a role in tearing apart families and communities. (Side note, lest we all get nostalgic for the pre-Reagan years: the economy in the 1970s was terrible, and everybody knew we couldn’t carry on like this forever.)

Anyway, Frank again:

But what has also made Trumpism possible is the simultaneous evolution of the Democrats, the traditional workers’ party, over the period I have been describing. They went from being the party of Decatur to the party of Martha’s Vineyard and they did so at roughly the same time that the Republicans were sharpening their deadly image of the “liberal elite”.

And so the reversal is complete and the worst choice ever is upon us. We are invited to select between a populist demagogue and a liberal royalist, a woman whose every step on the campaign trail has been planned and debated and smoothed and arranged by powerful manipulators. The Wall Street money is with the Democrats this time, and so is Silicon Valley, and so is the media, and so is Washington, and so, it sometimes seems, is righteousness itself. Hillary Clinton appears before us all in white, the beneficiary of a saintly kind of subterfuge.

Read the whole thing. Even if I don’t agree with all of it, there are useful insights in it.

The kind of social policies and moral causes pushed by the Democrats in specific and liberals in general worked to unravel families and communities as much if not more than Republican economic policies. Good luck getting partisans on either side to see their own complicity in this effect.

No matter who wins tomorrow, the unraveling is going to continue. I expect to consider the next president, no matter which one it is, as a distant figurehead who is a threat to my family and community, and to be endured, not supported. I did not feel this way about Obama, even though I did not vote for him either time. If Obama were about to be elected to a third term, though, I would absolutely feel that way about him, given the direction of his administration on religious liberty. The next president, I believe, is going to put this country at serious risk of more foreign wars, which I expect will be my duty to oppose. In my case, I have liked and disliked particular administrations, and liked and disliked the same administration, but on different issues. But never have I felt so alienated from the government. Hell, I’m so done with them that I’m not even angry about it. What’s the point of being angry? We have too much work to do at the local level.

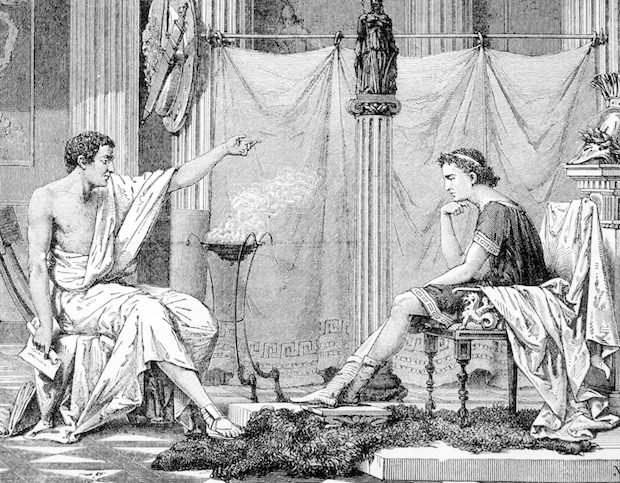

A reader sent in this good essay from First Things today, by philosophy professor John Cuddeback. In it, he talks about Aristotle and the election. Excerpts:

Aristotle envisions a common commitment to the virtuous life—or in any case a common conception of what the virtuous life is—as at the heart of political society.

But even if one grants Aristotle’s point in the abstract, does it have any relevance today?

I will not argue here that classical liberalism is wrong on this matter—though I think it is. I want rather to emphasize that if we are going to work for the renewal of our polity and local communities, we need to grapple with the fact that real human community requires more unanimity of thought and practice than we have realized.

More:

Aristotle’s position combines a clear conception of the ideal with a practical perception of what to do when the ideal is not realized. When the broader political community is not what it should be, then a man reasonably focuses his attention closer to home. Taken for granted here is that family and friends share a conviction that living virtuously is the only truly good human life, and that we need friendship and social solidarity in pursuing that great good.

This approach might appear at first a formula for simply receding from a political environment that one does not find “friendly.” Closer consideration, however, reveals a more subtle approach. At work here is a simple principle: Focus your energy where it can be most fruitful—on the common good.

Regardless of the broader climate, we can seek with family and friends to forge a fully human life —though in an unfriendly political environment it will be especially arduous. At least in these smaller communities we can try to put first things first, and thus all things in their proper place. In such communities we experience the kind of solidarity requisite for achieving human excellence in virtue.

Such attention to friendship, family, and local community does not entail an abandonment of the broader political process. On the contrary, building such cells of excellence is a fundamental requirement for the renewal of the broader polity.

Read the whole thing. Cuddeback never uses the term, but he makes a better case than I do (or at least a more succinct one) for the Benedict Option as a rational response to the dead ends of our national politics. Remember this John Adams quote?:

I must study politics and war that my sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. My sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history, naval architecture, navigation, commerce, and agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and porcelain.

Well, could it be that we must study St. Benedict and build the local churches and forms of community so that our sons and daughters, the children of strong families, will be able to study politics, so that their children may have the opportunity to study and practice all the arts of civilized life in the time of rebuilding to come?