Politics In A Culture Of Disintegration

Note: Please forgive me for not posting more these days. I came off of Walker Percy Weekend with a rather nasty bronchial infection that has kept me bed-bound since Sunday afternoon. Antibiotics seem to have turned the corner for me, a bit, but I was having so much trouble catching my breath that my doctor did something he’s never had to do for me before: prescribed an inhaler. That’s more information than you all needed to know, but I am actually touched by the private notes I get from readers when the posts slacken, asking if I’m okay. I am okay, just stuck in bed, and sleeping a lot.

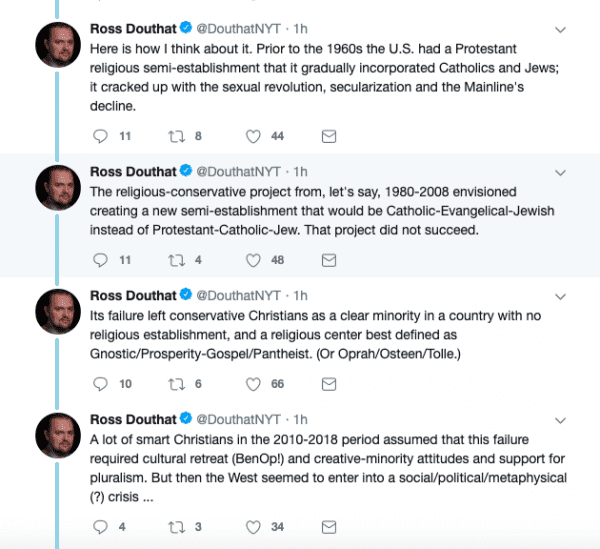

I can barely keep up with the many directions in which the Ahmari-French debate has gone, so I won’t even try. I do want to commend Ross Douthat for this contribution:

The word “integralism” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. There are various forms of integralism, but it generally means a formal integration of the religious and the political orders, and — as this is mostly a Catholic idea — placing Catholic moral and social teaching at the core of political order. The Catholic integralist blog The Josias defines integralism like this:

Catholic Integralism is a tradition of thought that rejects the liberal separation of politics from concern with the end of human life, holding that political rule must order man to his final goal. Since, however, man has both a temporal and an eternal end, integralism holds that there are two powers that rule him: a temporal power and a spiritual power. And since man’s temporal end is subordinated to his eternal end the temporal power must be subordinated to the spiritual power.

Integralism is intellectually rich, but it’s impossible to imagine it ever being possible in the United States. No need to go into it deeply in this space, but whatever its merits, integralism would not even be supported by most American Catholics. And the behavior of the US Catholic hierarchy in recent decades has made risible the idea that the public square should be ordered in some way by Catholic principles.

Don’t misunderstand me: though not a Catholic, I am personally far more amenable to an integralist order than you might think. It’s just that I believe it’s a complete fantasy right here, right now. It’s much less of a fantasy in Poland, which is overwhelmingly Catholic, or, in an Orthodox form, in Russia. Whether it’s a good thing, a bad thing, or something in between is a question worth exploring — but not in America.

Now, what’s interesting about Douthat’s points is that we did have a de facto soft integralism in the United States until the 1960s. There was no established church, of course, but our secular liberal democratic order was informed and buttressed by the common Christianity of the people. Tocqueville wrote about the critical importance of civic Christianity to the American experiment. Even John Adams saw it right there at the beginning:

We have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge or gallantry would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution is designed only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate for any other.

The 1960s really were a watershed decade. And, as Douthat said, the attempt during the revival of political conservatism to create a new religious center failed. The Catholic philosopher Michael Hanby has written profoundly about the meaning of the collapse of civic Christianity. What he has to say is really, really important, and relevant to the Ahmari-French dispute. Excerpts:

Such are the logical consequences of the sexual revolution, but to grasp more fully the meaning of its triumph, we must see that the sexual revolution is not merely—or perhaps even primarily—sexual. It has profound implications for the relationship not just between man and woman but between nature and culture, the person and the body, children and parents. It has enormous ramifications for the nature of reason, for the meaning of education, and for the relations between the state, the family, civil society, and the Church. This is because the sexual revolution is one aspect of a deeper revolution in the question of who or what we understand the human person to be (fundamental anthropology), and indeed of what we understand reality to be (ontology).

All notions of justice presuppose ontology and anthropology, and so a revolution in fundamental anthropology will invariably transform the meaning and content of justice and bring about its own morality. We are beginning to feel the force of this transformation in civil society and the political order. Court decisions invalidating traditional marriage law fall from the sky like rain. The regulatory state and ubiquitous new global media throw their ever increasing weight behind the new understanding of marriage and its implicit anthropology, which treats our bodies as raw material to be used as we see fit. Today a rigorous new public morality inverts and supplants the residuum of our Christian moral inheritance.

This compels us to reconsider the civic project of American Christianity that has for the most part guided our participation in the liberal public order for at least a century.

Hanby writes that liberalism cannot be understood as neutral:

One needn’t be ungrateful for the genuine achievements of American liberalism in order to question the wisdom of this project and its guiding assumptions. First, a purely juridical order devoid of metaphysical and theological judgment is as logically and theologically impossible as a pure, metaphysically innocent science. One cannot set a limit to one’s own religious competence without an implicit judgment about what falls on the other side of that limit; one cannot draw a clear and distinct boundary between the political and the religious, or between science, metaphysics, and theology, without tacitly determining what sort of God transcends these realms. The very act by which liberalism declares its religious incompetence is thus a theological act. Its supposed indifference to metaphysics conceals a metaphysics of original indifference. A thing’s relation to God, being a creature, makes no difference to its nature or intelligibility. Those are tacked on extrinsically through the free act of the agent.

Liberalism’s articles of peace thus mask tacit articles of faith in a particular eighteenth-century conception of nature and nature’s God, which also entails an eighteenth-century view of the Church. Moreover, liberalism refuses integration into any more comprehensive order over which it is not finally arbiter and judge. It establishes its peculiar absolutism, not as the exhaustive dictator of everything one can and cannot do—to the contrary, liberal order persists precisely by generating an ever expanding space for the exercise of private options—but as the all-encompassing totality within which atomic social facts are permitted to appear like so many Congregationalist polities, the horizon beyond which there is no outside. Hobbes’s thought aspired to this kind of sovereignty, and Locke’s thought more effectively achieved it, but it was Rousseau who really understood it.

As I wrote in some detail in The Benedict Option, the Sexual Revolution was also an anthropological event, and was not easily distinguishable from economic and cultural atomization that had been underway in Western civilization for many decades. We don’t need to get into all that here; it’s enough to say that when Christianity, in its more or less orthodox forms, declined in American life, so too did the meaning of liberalism. We can argue over whether this decline was baked into liberalism’s cake from the beginning (as I believe), or that it results from an error that can be fixed. Hanby anticipates here, I think, the core of the Ahmari-French dispute:

There are important debates about how and why the liberal order has attained this dangerous, all-encompassing absolutism. Patrick Deneen evokes its main contours in his American Conservative article “A Catholic Showdown Worth Watching.” He describes a debate between “radical” Catholicism and “neoconservative” Catholicism. The neoconservative Catholic often draws attention to a progressive fall from classical liberalism, while the radical Catholic sees our current crisis as the outworking of liberalism’s deepest premises. Not surprisingly, therefore, the radical Catholic thinks it necessary to engage liberal order in a fundamental, ontological critique, while the neoconservative Catholic settles for a moral, sociological, legal, or political approach. He thinks energies are best spent recalling America to its founding principles, in hopes of preserving the dwindling space of freedom for Christians in the public square. The radical Catholic is more likely to counsel preparing for the day when filing another lawsuit is no longer enough. The same contrasts play out among Protestants, largely along the same lines.

This is a debate worth having, for it addresses fundamental questions about the structure of being, the nature of human beings, and the relations between nature and grace, faith and reason, and the political and ecclesial orders. I am inclined toward the “radical Catholic” side of this debate, convinced that unless and until we engage in a thorough reassessment of the metaphysical and crypto-theological conceits of liberalism, we will find ourselves coopted by it, unwittingly serving its project even as we bemoan and increasingly are afflicted by its excesses.

In this passage from Hanby is why I have not been fully convinced that either French or Ahmari offers a solution. Hanby says that the philosophical debate over liberalism is being eclipsed by events in the real world. He delivered the paper a few months before the Obergefell decision, please note, but he’s talking here about how the popular laws permitting same-sex marriage and protecting this and that form of transgenderism reflect an anthropological shift in our culture, in which the core beliefs of Christian anthropology (“what is man?”) are negated. Hanby again:

This rejection of nature is manifest in the now orthodox distinction between sex, which is “merely biological,” and gender, defined as a construct either of oppressive social norms or of the free, self-defining subject—one often finds protagonists of this revolution oscillating back and forth between those polar extremes. And this sex–gender distinction, in turn, is premised upon a still more basic dualism, which bifurcates the human being into a mechanical body composed of meaningless material stuff subject to deterministic physical laws and of the free, spontaneous will that indifferently presides over it. This anthropology denies from the outset that nature and the body have any intrinsic form or finality beyond what the will gives itself in its freedom, and thus it fails to integrate human biology and sexual difference into the unity of the person. Indeed, the classical Aristotelian nature and the Christian idea of the human being as body and soul united as an indivisible and integrated whole are excluded from the outset.

Whether this is the logical outworking of the metaphysical and anthropological premises of liberalism or a radically new thing—and Hans Jonas’s analysis would suggest that these are not mutually exclusive alternatives—it marks a point of no return in American public philosophy. And it effectively brings the civic project of American Christianity to an end.

This is not to say that Christians should disengage or retreat, the usual misinterpretation of the so-called Benedict Option. There is no ground to retreat to, for the liberal order claims unlimited jurisdiction and permits no outside. We do not have the option of choosing our place within it if we wish to remain Christian. We cannot avoid the fact that this new philosophy, once it is fully instantiated, will in all likelihood deprive Christians of effective participation in the public square. Hobby Lobby notwithstanding, appeals to religious liberty, conceived as the freedom to put one’s idiosyncratic beliefs into practice with minimal state interference, are not likely to fare well over the long haul as these beliefs come to seem still more idiosyncratic, as religious practice comes into conflict with more “fundamental” rights, and as the state’s mediation of familial relations becomes ever more intrusive. And attempts to restore religious freedom to its proper philosophical place, as something like the sine qua non of freedom itself, presuppose just the view of human nature and reason that our post-Christian liberalism rejects from the outset.

What is he saying here? That changes happening in our culture, and reflected in our laws, are so revolutionary that Christianity doesn’t make sense. Hanby writes, “Indeed, the classical Aristotelian nature and the Christian idea of the human being as body and soul united as an indivisible and integrated whole are excluded from the outset.” We Christians are left to try to make sense of this in the shards of what was once a coherent culture.

People made fun of Sohrab Ahmari for being furious over Drag Queen Story Hour, but they don’t understand that DQSR is a condensed symbol of this revolution. That a sexual outlaw figure (the drag queen) can be normalized and bourgeoisified, and ushered into the public square (library) as a teacher of children, and this would be taken as progress — well, that shows you how far we have gone into the post-Christian world. About condensed symbols, here’s something I posted explaining the concept. Here I’m quoting readers:

[The reader said:] With that said, why the heck are conservative Christians so freaked out about homosexuality above and beyond virtually every other “sin.” I’m no biblical scholar to be sure, but even if homosexuality is verboten under the Bible, so is divorce, fornication, and adultery. Are there florists and caterers that will not service weddings unless the bridge and groom are virgins? Why do Christians fight against gay marriage, yet don’t fight for laws to prohibit divorce or criminalize adultery?

[Raskolnik replies:] Some variation of this question pops up so frequently that I figured it would be worth writing a fairly involved answer that I could then copy and paste as necessary. On the one hand, the premises of this question don’t really make any sense from an orthodox Christian perspective; on the other hand, you’d have to be an orthodox Christian to understand why, so it’s probably worth spelling out exactly what the issue is.

So: the thing to understand here is that the vast majority of Christians are not “freaked out about homosexuality above and beyond” every other sin, sexual or otherwise. I understand that from your perspective it may appear to be so, but please understand that this is simply a false impression driven by the media and various political interests. Most of the Christians I know, for example (myself included), are far more concerned about the extreme prevalence of pornography than they are about homosexuality. However, pornographers and pornography consumers are not a politically powerful lobby, and as yet there is no one who identifies as “pornosexual,” thus there is no narrative of the oppression of the poor pornosexuals to tap into Selma envy.

Back in the 60’s, the sociologist Mary Douglas came up with the idea of a “condensed symbol.” The idea is that certain practices or ideas can become a kind of shorthand for a whole worldview. She used the example of fasting on Fridays, which the Bog Irish (generally lowerclass Irish Catholics living in England) persisted in doing, despite the fact that their better-educated, generally-upperclass clergy kept telling them to give to the poor or do something else that better fit with secular humanist mores instead. Her point was that the Bog Irish kept fasting, not due to obdurate traditionalism, or some misplaced faith in the “magical” effectiveness of the practice, but because it functioned as a “condensed symbol”: fasting on Fridays was a shorthand way of signifying connection to the past, to one’s identity as Irish, as well as to a less secularized (or completely non-secular) vision of what religious practice was all about. It acquired an outsized importance because it connected systems of meaning.

I bring up the notion of “condensed symbol” because I think that’s the best way to understand what’s going in (what you perceive to be) the “freakout” about homosexuality. The freakout isn’t about homosexuality per se, it’s about the secular world shoving its idea of sexual morality down the throats of orthodox Christians. If you haven’t read Rod’s piece Sex After Christianity, you really should, and if you haven’t, I think you should be able to connect the dots between the Christian cosmology of sex and the Christian opposition to same-sex marriage as a “condensed symbol” of Christian resistance to secularism writ large.

Because the fact of the matter is that, for a variety of reasons, some easily understandable from a non-religious perspective, some of them perhaps less so, participating in a same-sex marriage has become the 21st century equivalent of making offerings to Sol Invictus. A Roman might just have easily asked, “What’s the big problem? Why not just make the offerings? Don’t they want to be a part of Roman society?” A more intelligent Roman might even have asked, “They don’t even believe in the divinity of the Emperor anyway. Why can’t they just burn the incense, which they literally believe has no effect on anything whatsoever?” Hopefully you can see the connection here; Christian opposition to the Roman cult of Sol Invictus, like Christian opposition to same-sex marriage, is about a whole lot more than burning some incense or baking a cake.

It’s not about Drag Queen Story Hour per se; it’s about the changes that have taken place within society and culture that make Drag Queen Story Hour possible, and even popular. Plus, as we have learned, major corporations have taken up homosexuality as a crusade, leading to absurdities like this:

Blue symbolises male attraction, pink female attraction, and yellow attraction to other genders. pic.twitter.com/DY1qhJQv5J

— Budweiser UK (@BudweiserUK) May 31, 2019

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

… but also serious things, like the power of Big Business coming down like a sledgehammer on the State of Indiana when it tried in 2015 to pass a state version of the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Woke Capitalism has become a major factor in American public life. Companies are beginning to act like governments — and always against social and religious conservatives.

OK, so what does this have to do with Ahmari and French and their dispute? As I’ve said on Twitter, I’m about 75 percent with Ahmari, and 25 percent with French — but 100 percent with the Benedict Option. Here’s why.

Ahmari says that cultural and religious conservatives have to fight back, and fight hard. I’m with him! I’ll vote for the counterattack! But what does that mean? And what are we fighting for?

Despite what you may have heard from people who haven’t read my book, I am not a Ben Op quietist. I believe people like me have to fight hard for our liberties. But contrary to my friend Rusty Reno, I don’t have faith that “we have voters behind us.” I would love to be wrong. I think we have more voters behind us than Republican pols think, and certainly the bizarre appearance on the political scene of Donald Trump opens up possibilities, good and bad. But mostly I think we are playing a weak hand — in part for the reasons that Michael Hanby discusses in his essay.

The hole in Ahmari’s view is the belief that there remains a significant core of religiously and socially conservative Christians. It’s just not there. It’s Moralistic Therapeutic Deism all the way down. To be sure, there are pockets of resistance, and hope, among all kinds of Christians (Evangelicals, Catholics, Orthodox, and yes, even some Mainliners). I meet these people all the time in my Ben Op travels. They’re quite inspiring. Mostly, though, they tell me that they are a minority within their own Christian circles. They tell me that most Christians they know — and these are all conservatives — don’t even really understand how much ground we have lost under our feet. They can’t imagine that something like this could happen, therefore they’re in denial.

The tectonic shift that Michael Hanby mentions — and that Philip Rieff discusses from a different angle in The Triumph of the Therapeutic — has occurred within the churches too. I am prepared to be pleasantly surprised, but without a significant culture of social conservatism, I don’t know where the political base comes from. Christianity in America is not doing well, at all. The integralists and their fellow travelers are pretty much on the nose with their diagnosis: the problem is radical individualism cut off from shared metaphysical commitments. But honestly, how can we Christianize the polis when we can’t even Christianize the churches?

I thought it was deeply unfair to characterize David French, who has fought so many courtroom battles on behalf of religious liberty, as any kind of weakling. It is fair, though, to describe French as someone devoted to classical liberalism in a conservative key. He wouldn’t dispute that. I don’t share David’s confidence in liberalism, but I do believe that this is the system we’re going to have for a while yet, and that we need to be able to work effectively within it to defend our liberties. As we small-o orthodox Christians are a minority, we had better be damn good at defending ourselves within the institutions of liberalism, using liberalism’s rules. Yes, they’re stacked against us — but what else do we have?

Unlike David French, I presume, I am not confident that liberal democracy will be able to withstand the loss of a common religion, even one as attenuated as civic Christianity was. The logic of liberalism consumes it. Look at this big story The New York Times is pushing now: on what life is like through the eyes of gender nonbinary people. It is liberalism taking to its ne plus ultra fulfillment. This passage is emblematic (“they” refers to an individual):

They thought back, during one of our many conversations, to the aftermath of their own decision to have a vagina surgically constructed, a decision made in the absence of the language and intricate self-understanding that defines their life now. They’ve always been sexually attracted to women and “femme-leaning” people. “I was having sex with women,” they said, “and a lot of women who have sex with women use strap-ons. I refused to even consider it. I couldn’t reconcile having made the choice to get rid of the real thing with using a plastic replica. The idea put me into shock; I would dissociate, become a deer in headlights. Wearing a strap-on symbolized a massive mistake. I felt that exploring it would lead to massive regret. But as the years went on, I started to dabble. It was hot, fun.”

Our talk shifted again from the past to the future. Jacobs spoke about foreseeing a time when people passing each other on the street wouldn’t immediately, unconsciously sort one another into male or female, which even Jacobs reflexively does. “I don’t know what genders are going to look like four generations from now,” they added, allowing that they might sound utopian, naïve. “I think we’re going to perceive each other as people. The classifications we live under will fall by the wayside.”

Among the voices of the young, there are echoes and amplifications of Jacobs’s optimism, along with the stories of private struggle. “There are as many genders as there are people,” Emmy Johnson, a nonbinary employee at Jan Tate’s clinic, told me with earnest authority. Johnson was about to sign up for a new dating app that caters to the genderqueer. “Sex is different as a nonbinary person,” they said. “You’re free of gender roles, and the farther you can get from those scripts, the better sex is going to be.” Their tone was more triumphal: the better life is going to be. “The gender boxes are exploding,” they declared.

A New Jersey-based therapist in her 50s, who describes herself as a butch lesbian and who has worked with nearly two dozen nonbinary high school and college students, is more circumspect. She guessed that many of her assigned-female nonbinary clients would once have lived as butch or — a subcategory — stone butch lesbians. “Are we just being faddish in the wish for more and more individualized identities?” she asked. And what percentage of the nonbinary kids now coming to her will be calling themselves nonbinary 10 or 15 years in the future? “To tell you the truth, I can’t be sure.” But despite her skepticism, her sense is that something urgent is going on, that new and necessary territory is being delineated. She’s not, at base, at odds with Jacobs, who wonders if we will all gradually question whether “the gender binary is inherent to human experience.”

Oh yeah, Emmy Johnson, it’s gonna be utopia, baby. Emmy is the near future. The integralism of late liberalism is disintegration with an erection. There is nothing within progressivism to stop this dis-integration — and with Woke Capitalism triumphant, the propaganda from mass media and advertising will keep wedging us farther and farther apart. The strongest forces in this culture are forces of disintegration, and nothing so far has emerged, or can emerge out of liberalism to put a halt to it.

I will use whatever powers liberalism grants me as a citizen to fight for the Good, but my concern is not saving liberalism. My concern is primarily how to live faithfully as a Christian, to spread that faith and to pass it on to my children, and their children. The faith is many things, one of them being Logos. The darkness cannot comprehend the Logos. We are living in a time when the darkness is doing its best to snuff the Logos. As with St. Benedict of Nursia, our vocation in this time, and in this place, may not be to save the Empire, but to develop resilient ways of living that keep the light of Logos incarnate in our own hearts, families, and small communities, burning through this long night. Maybe our task is to provide the rich soil from which something new will grow, long after we have departed.

Whether we’re talking about renewed liberalism, or post-liberalism, none of it matters if the faith has died in the hearts and minds of men. That is what we’re fighting for. We’ll be fighting for it even if we elect the best possible politicians (from a Christian point of view), because our debased politics are not the cause of our crisis, but only a symptom. This is why I push for the Benedict Option.

I’m prepared to believe I’m wrong about that. If you think I am, what’s your plan? How are you planning to save America if you can’t be confident that you can save your own family from apostasy? I’m serious.

UPDATE: Just saw via Twitter that Michael Brendan Dougherty, a traditionalist Catholic, pretty much addressed this in a column last year. Excerpt:

I would gently suggest that the integralist critics of liberalism may be focusing too much on the theory of liberalism and not enough on the condition of their Church.

We can look at liberalism not just as an ideology of individual rights superintended over by a powerful central authority. It is also as a practical negotiation made among “those who conduct themselves as worthy members of the community” within what used to be called Christendom. The Catholic Church in America may have lost the vigor and “fecundity” that Leo XIII observed in it over a century ago. And insofar as it has, it has lost some of its practical bargaining power.

See how the Reverend John I. Jenkins, the president of Notre Dame University, took several contradictory positions on the contraception mandate. His school became a plaintiff, arguing against it, as an infringement of religious liberty, in the highest courts in America. But, faced with dissension among professors, he reversed himself.

This level of dissension on matters of moral doctrine is everywhere in Catholic institutions, not just in universities but on the boards of Catholic health-care and charitable organizations and in diocesan secondary and primary schools. Such dissension characterizes the whole Church in America, a country where the second-largest reported religious affiliation is “ex-Catholic.”

More:

The more urgent need for the Church’s liberty in the United States may not demand an attempt to transcend 500 years of a mistaken political philosophy. Instead it may be a matter of looking at a decades-long problem of disaffection and apostasy. The Church also suffers from a massive scandal of immorality and criminality among its prelates. These crimes, so long unaddressed by higher authorities in the Church, manifestly call into question not just the Church’s commitment to its doctrines but its fitness to lead so many civic institutions and to control so many resources. Are America’s Catholic bishops conducting themselves “as worthy members of the community?” And if not, can we expect their religious liberty to remain sacrosanct?

If the Church recovered its vigor and its authority internally, then the neighbors with whom it lives peaceably, and among whom we do so many good works, would be less inclined to test our commitments, or our patience. The social Kingship of Christ may proceed to impose duties upon all nations, but it begins with the words: Physician, heal thyself.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.