The Two Faces Of Cardinal O’Brien

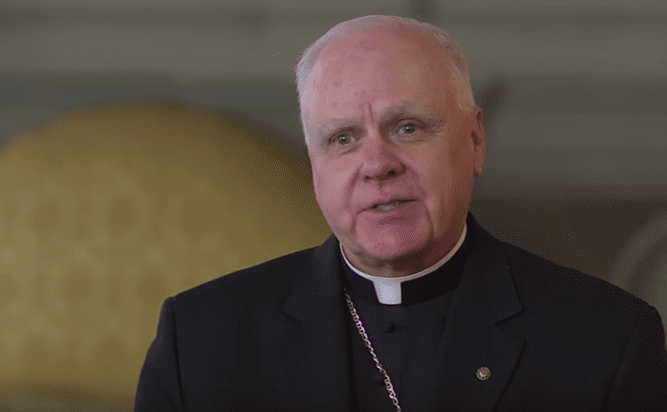

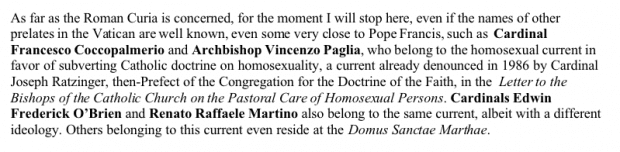

Cardinal Edwin F. O’Brien, archbishop emeritus of Baltimore, shows up in the Vigano letter here:

How could that be? In 2005, Catholic News Service reported:

The archbishop overseeing a Vatican-run inspection of U.S. seminaries said there is no room in seminaries for men with strong homosexual inclinations even if they have been celibate for a decade or more. “I think anyone who has engaged in homosexual activity, or has strong homosexual inclinations, would be best not to apply to a seminary and not to be accepted into a seminary,” said Archbishop Edwin F. O’Brien, head of the U.S. Archdiocese for the Military Services. Archbishop O’Brien, who is coordinating the visits to more than 220 U.S. seminaries and houses of formation, said even homosexuals who have been celibate for 10 or more years should not be admitted to seminaries. “The Holy See should be coming out with a document about this,” Archbishop O’Brien said in an interview with the National Catholic Register newspaper. The call for the visits came after a wave of abuse allegations and revelations about how dioceses handled those cases.

Emphasis mine.

Well, here’s a story for you. Ron Belgau is a Catholic who lectures widely on Biblical sexual ethics and his own experiences as a celibate gay Christian. He is the cofounder, with Wesley Hill, of Spiritual Friendship, a group blog dedicated to exploring how the recovery of authentic Christian teaching on friendship can help to provide a faithful and orthodox response to the challenge of homosexuality. In 2015, during Pope Francis’s visit to Philadelphia he and his mother, Beverley, were invited to speak at the World Meeting of Families about how Catholic families can better respond to gay, lesbian, and bisexual persons in their midst.

Recently, Ron and I spoke by phone about the burgeoning McCarrick scandal. In that conversation, Ron brought up something that he wasn’t willing to share at the time. Now, though, he’s given me permission to bring it forward. Ron writes about an experience at the national conference of Courage, a ministry to gay and lesbian Catholics who seek to live in chastity and celibacy out of fidelity to Church teaching:

In your most recent post on the fallout from Archbishop Vigano’s letter, you wrote:

For years I’ve been told that the 2005-06 Vatican-ordered investigation of US seminaries was a sham because it was led by then-Archbishop, now Cardinal, Edwin O’Brien — believed by some insiders to be part of the lavender mafia, the gay lobby within the Church intent on protecting its own. In his testimony, Vigano says that O’Brien is indeed part of this group. How is it possible for anybody Rome appoints from within the Church to investigate now? It’s not.

I can add some first-hand testimony about O’Brien and the dishonesty of the 2005-2006 seminary investigation.

I was at the 2005 Courage Conference, where then-Archbishop O’Brien celebrated one of the Masses. After Mass, he approached a friend of mine and me, and asked us if we had considered studying for the priesthood. We both had. He encouraged us both to apply for the priesthood and said we should apply to become chaplains in the military (he was Archbishop of the Military Services at the time).

The following month, in his role as head of the 2005 seminary visitation, he told reporters that men with homosexual inclinations should not be admitted to the seminary, even if they had been celibate for more than a decade. Yet he had been recruiting at Courage, a conference for men and women struggling with homosexuality.

I know nothing about Cardinal Edwin O’Brien’s personal life, so I can’t confirm Vigano’s allegation that he belongs to a “homosexual current” in the Church. But the situation he was complicit in creating—an environment where same-sex attracted men are widely recruited into the priesthood but face expulsion for any acknowledgement of their sexuality—is an important part of the systemic explanation for why bishops and others with power in the Church hierarchy have been able to prey on seminarians and young priests.

It breeds a culture of duplicity. Even if there are no predatory superiors, and every man in the seminary remains faithful to his vow of celibacy, they are internalizing the lesson that sometimes, you do one thing, while telling the laity that you’re doing the opposite. And this is not only happening to the gay seminarians: it’s happening to the straight ones, as well, who can see what is happening, and are taught to shut up and repeat the lie.

Because Ron is an out gay Catholic who has a ministry to gay and lesbian Catholics who want to live faithfully to Church teachings, I asked him how orthodox reformers can deal with predatory gay clerics like McCarrick without turning it into a witch hunt targeting all gay Catholics. He responded:

The first point is obvious, but rarely stated: the only way to bring justice is to effectively investigate allegations against men like McCarrick and Nienstedt and punish them if the allegations are substantiated. Right now there is no effective way to do this inside the Church. Most of what we’ve learned about the scandal we have learned because of civil lawsuits, criminal investigations, and investigative reports in the news media.

And in fact those who bring these kinds of allegations to superiors may face retaliation by a system which protects its own.

Unfortunately, These investigations take a lot of time and resources. It’s easier to write an article blaming the scandal on gays—or the closet, or clericalism, or celibacy, or Vatican II, or the Catholic Church, or the patriarchy, or whatever the writer’s particular hobby horse happens to be—than it is to do the kind of in-depth investigation that Richard Sipe did to expose McCarrick.

While sex is no doubt sensational, an important dynamic in these scandals is financial. McCarrick was able to get away with this for so long in part because he was a very successful fundraiser. He founded the Papal Foundation in 1988, and raised millions for Catholic causes. The same is true of Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado, the disgraced founder of the Legionaries of Christ, who allegedly raised billions for the Legion.

The allegations against Maciel were widely publicized for years before he was finally removed from office; the allegations against McCarrick were at least widely known. How many of their financial supporters were aware of these allegations? Did they think it was important to investigate?

If we want to clean up the Church, we have to eliminate the rot at the top, and that depends on identifying and removing corrupt leaders who have covered up sexual abuse, sexually harassed seminarians, and so forth (the scandals du jour are not the only kinds of corruption which weaken Catholic witness).

The next point is that scapegoating is one of the most effective ways powerful insiders deflect attention from their own crimes and cover-ups to focus people’s anger on gays—or the closet, or clericalism, or celibacy, or Vatican II, or the Catholic Church, or the patriarchy, or whatever.

O’Brien is an obvious case: he took a very strong public stand against allowing men with homosexual inclinations into the seminary or priesthood. But that was window dressing. He had no intention of actually doing what he said needed to be done. But he helped to shift the conversation about the systematic cover-ups by bishops revealed in 2002 into a conversation about who gets admitted to the seminary—a question that was considerably less awkward for him and his fellow bishops to talk about.

In the contemporary scandal, it’s a lot easier for a bishop to announce that he is opposed to the homosexual subculture in the Church than it is to actually push to investigate allegations against his own colleagues and mentors—or admit his own complicity in the crimes and cover-ups.

A lot of Catholics speak as if the “lavender mafia” refers to every same-sex attracted priest or seminarian, and all of them are either involved in the kind of predation McCarrick is accused of, or else are silently protecting and enabling such predators. It is actually much more complicated than that. As Eve Tushnet recently pointed out,

The term “homosexual subculture” can mean a lot of things. Three obvious examples are the “situational homosexuality” of all-male environments like boarding schools or prisons, or seminaries; a network or friendship group in which men are open about their sexuality to one another even if they are completely closeted in their public life; or a deeply hidden, furtive “subculture,” more like being on the down low, in which men don’t even acknowledge to themselves the meaning of the fact that they consistently seek out sex with men or teenage boys. These subcultures can overlap, and it seems like all of them have played some role in the Church.

If we want to investigate and root out the kind of corruption that has been revealed in the McCarrick scandal, we need victims to come forward. Many of those victims are homosexually inclined priests or seminarians. To the extent that we focus on scapegoating all gays for the scandals, we make it harder for these seminarians and priests to come forward.

Scapegoating all gays—or all gay priests and seminarians—for this scandal also blurs the distinction between those who have homosexual inclinations, but do not act on them; those who have been coerced or seduced into sex by those with power over them; those who have engaged in consensual relations with adults they have no power over; those who have sexually harassed or abused those under their power; and those who have sexually abused minors.

A prosecutor who is serious about clearing out a corrupt organization makes distinctions between the crimes of those lower down the ladder and those at the top. On the other hand, a mafia boss works hard to make sure that everyone in his organization stays silent. Scapegoating all gays is a strategy for keeping everyone silent, not a strategy for seeking cooperation from the innocent or the less guilty to investigate and convict the most guilty.

A final point: a lot of Catholics talk as if the only meaningful vocations are either marriage or priesthood/religious life. If we talk this way, a lot of gay Catholics who are trying to follow Church teaching will see the priesthood/religious life as their only vocational option.

I have never recommended the priesthood or religious life to same-sex attracted men, primarily because I think it’s an unhealthy environment. I was mildly harassed when I was discerning for the priesthood almost twenty years ago, and it was clear to me that there was something deeply unhealthy in the sexual culture of the priesthood. Subsequent experience over the last twenty years has only reinforced that concern.

In a recent article in Public Discourse, I cited C. S. Lewis’s claim that “in homosexuality, as in every other tribulation,” God’s works can be made manifest. That is, “every disability conceals a vocation, if only we can find it, which will ‘turn the necessity to glorious gain.’” The more that we think about ways to live out that vocation as a layperson in the world, the fewer men will be inclined to seek refuge in the priesthood, despite not having a true calling to the priesthood or religious life.

In The Benedict Option, you wrote,

A congregation cannot be a monastery, but there is no reason why it should not reach out to hold its single members closer, as members of the church family. As Brother Augustine told me, there are days when he feels exhausted by the rigors of the monastic life—and on those days, he relies on the charity of his brother monks to carry him. Why can’t we serve our unmarried community members in a similar way?

Moreover, if a parish community has the resources, it should consider establishing single-sex group houses for its unmarried members to live in prayerful fellowship as what you might call lay monastics. It is hard to live chastely in a culture as eroticized as ours, especially when there is so little respect for chastity. One expects this from the world, but the church must be different.

All unmarried Christians are called to live celibately, but at least heterosexuals have the possibility of marriage. Gay Christians do not, which makes their struggle even more intense.

Worse, too many gay Christians face rejection from the very people they should be able to count on: the church. The angry vehemence with which many gay activists condemn Christianity is rooted in large part in the cultural memory of rejection and hatred by the church. Christians need to own up to our past in this regard and to repent of it.

But that does not mean—and it cannot mean—that we should abandon clear, binding biblical teaching on homosexuality. Gay Christians, like all unmarried Christians, are called to a life of chastity. This is a heavy cross to bear, but one that cannot in obedience be refused.

If Christians take that advice to heart, then I believe that we can both investigate and clean out corrupt homosexual prelates like McCarrick, and make the Church a more hospitable place for gay and lesbian Christians who are striving for chastity, without scapegoating.

It’s possible to have a healthy and integrated sexuality even with ongoing struggle with disordered attractions. But the current culture in the Church is making that harder, not easier, for most gay and lesbian Christians who are striving to remain faithful.