The Nigel Farage Forever Tour

It was an event as throwback as its headliner.

On a sleepy spring night in “Sleepy Joe’s” Washington last week, I slipped into an event seemingly out of time and place: a mass gathering put on by FreedomWorks at a Washington steakhouse with pioneering Brexit leader Nigel Farage. Everything about it screamed not 2021: from the keynoter, a transatlantic comrade of former President Trump, to the host, a libertarian-minded outfit that has for now faded from center stage since the end of “the libertarian moment,” to the post-vaccine size of the crowd (about sixty, the largest I’ve been in since the South Carolina primary), to the location. The reality of the city’s restaurant scene has long evolved past its apparently enduring reputation as exclusively a steakhouse town (and maybe Cafe Milano). Good thing for the esteemed Charlie Palmer’s that there are a number of politicos, especially Republicans, that dine like it’s 1995.

Indeed, as conceded by one attendant: “Everyone’s depressed.”

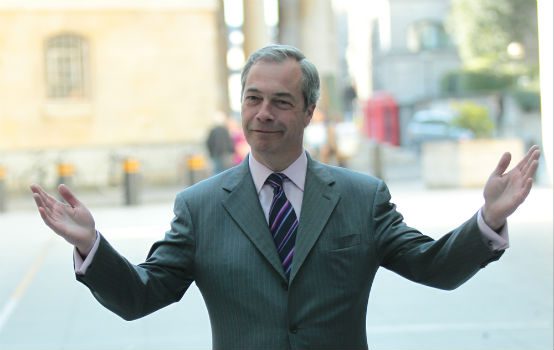

But against this backdrop—the banishment of their champion, Trump, and from a town run by among the most zealous COVID commissars anywhere—a man perhaps now a citizen of the wrong country came to give a pep talk, or at least remind the crowd of his otherworldly charisma. Long a devotee of longshot causes, the former United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) leader argued from experience that in politics it is exactly when one’s enemies appear most hegemonic that they’re secretly “at their weakest point.” It would sound like crackpot stuff coming from anyone besides the architect of Britain’s separation—or emancipation, as Farage sees it—from the bureaucracy that governs much of the rest of Europe, the largest economic zone in the world. The man knows when to play the hits. German Chancellor Angela Merkel? “Even worse in person.”

“There are only two tragedies in life. One is not getting what you want, the other is getting it,” arms dealer protagonist Yuri Orlov, a wily man perhaps after Farage’s own heart, says in the 2005 film Lord of War. Though not quite an American president, Farage, like Bill Clinton and Theodore Roosevelt (who left office as young men) has in common the achievement of a life’s ambition at a relatively early age. Death came for the latter, and destruction of contemporary reputation has come for the former, two fates Farage doubtless wants to avoid. It is not clear what the path forward for him is: an ally of convenience with Boris Johnson, perhaps the only thing Farage shares with the British establishment is the knowledge of the prime minister’s general untrustworthiness. His other most significant contact, Donald Trump, is no longer a head of government.

So what is Farage to do? Well, he can go on tour.

And that he is. Backed by FreedomWorks, an entourage has formed around the figure that views him as a ticket back to prominence, or at least a payout. Farage brings preternatural, dogged energy to seemingly any cause he lends his voice (“he’s a magnet,” said one interlocutor who saw him in Los Angeles last week). Indeed, if Farage is a rock star on the conservative circuit, he is keeping rockstar hours: in California on Wednesday, at Charlie Palmer’s across the country on Thursday, and by Friday at Elba-a-Lago in Florida. His “diary” that he is keeping, on YouTube, showed him in a full suit on a Saturday morning at Dallas Fort Worth airport, perhaps adding further to suspicions the species has a time traveler.

“Faragism” is more dispositional than encyclical. It’s been written that Farage didn’t so much have a macroeconomic emphasis in his eventually victorious crusade against Brussels as a horse trader’s hatred of regulation, a wheeler-dealer’s disgust toward the nanny state.

But he’s no doctrinaire libertarian. Like many right-leaning in the West these days, Farage sees only ominous stuff out of Beijing. “One of my biggest focuses now that most of Brexit is over has been the rise of China,” Farage said in a recently self-published video. “Or, to be more accurate, the rise of the Chinese Communist Party and their totalitarian attempt to shut down democracy, to take over the world.” Indeed, in my first meeting with him, Farage painted a picture of wholesale purchase by the Chinese of much of the English world, certainly in New Zealand, Canada, and his motherland.

If Farage flirts with a different country—the British Empire never fell, it just changed capitals to Washington, it’s often been said—then he has that in common with a man YouTube audiences have a similar appetite for: the late Christopher Hitchens. Farage is a former stockjobber and politician, while Hitchens was a prolific writer, but the similarities are there, extending to a noted love of the bottle and a smoke, balms for a sharp tongue.

The particulars of Farage’s politics are more similar to Hitchens’ younger brother, Peter, however. At the Washington event, Farage expressed particular glee that London had recently sent in the Navy in a shellfish dispute with Paris, invoking Trafalgar and Napoleon. His opinion on the German chancellor notwithstanding, Farage clearly concurs with Peter on missing the pre-Churchill primacy of that old pastime, taking it to the French.

“What joy to be in conflict with the French again, our ancient and hereditary foes,” Hitchens wrote in his Mail On Sunday column this week. Of course, though they largely agree, Hitchens doesn’t seem to much care for Farage, deploring his realpolitik with Johnson. Gloriously confirming his status as the paleocon Jean-Paul Marat, Hitchens wrote last year “Why did it take Nigel Farage so long to work out that Al Johnson,” as he calls the PM by his first name, “is a metropolitan liberal? Could it be that Mr Farage is a bit of a liberal himself?”

Outside the event, I find the man himself. He says he remembers me, with a politician’s gift of never forgetting a face, if not always memorizing the name. The strange admixture that results from a life on the road is not lost on him. Four years ago, he told the BBC that he was “53, separated, skint.” He told me he was in the market for a great woman, about 55, and it would also be great if she was the understanding and plutocratic type. Or, as he once told the Financial Times over six pints, a bottle of wine and two glasses of port: “I am what I am.”