Populist Uprisings and the Inversion of Inflation

Hotly contested elections are nothing new in this country, nor are elections fought around themes of populism. These battles have been fought as far back as the first iteration of American populism with James Weaver and his protégé William Jennings Bryan in the 1890s, and as recently as 2012 with Ron Paul and 2016 with Donald Trump. What is interesting, however, is the paradoxical situation in which the socioeconomic circumstances in these two periods are vastly different—quite literally opposite—but the rage generated is almost identical.

It’s worth outlining the key concepts to make sure they are understood first, and to clarify that the unifying theme here is the way economics interplay with issues of political power, specifically as they pertain to monetary issues. The importance of this monetary connection cannot be understated, particularly with ever new rounds of printed stimulus being injected into our economy.

When reading about the 1890s, the terms “bimetallism” and “free silver” often get thrown around. These were terms widely used and understood that argued for a shift in American monetary policy. From 1873 on, the United States had a hard gold standard for the dollar, removing the silver dollar from circulation. The effect of this decision was massive deflationary pressure designed to protect the value of the currency. As Iowa Republican Hiram Price said in 1880, because of this “a day’s labor will buy more of anything that a man eats or wears than it ever would at any time in… the history of the country.”

While this effect did materialize, the vast majority of rural Americans could not take advantage due to one factor: debt. The 19th century was the time of America’s ongoing westward expansion, and many poor Americans took cheap loans to pay for cheap land on the frontier. Rather, the loans were cheap before 1873. Silver was extremely abundant and its presence in the currency had an inflationary effect. An inflated currency is a bad thing for those with savings, who see the value of these savings made worthless, but a very good thing for those with large debts. As the value of each dollar decreases, the number of dollars owed to the bank doesn’t change. Acquiring more dollars becomes easier, thus facilitating easier debt repayment.

By removing inflationary silver, the gold standard led to the inverse. Prices fell, meaning that farmers couldn’t grow and sell enough to repay their debts. This was a good move for the value of the currency, but disastrous for rural Americans, who dubbed the betrayal of “King Silver” as the “crime of ‘73.”

Many populists and rural Americans believed that the gold standard that came in was a monetary system designed to help the powerful: those with Gilded Age assets who wanted to protect the value thereof. State banks could print their own money without oversight from the Federal government, leading many populists to believe that this was a corrupt system designed to favor wealthy elites with no democratic legitimacy. Weaver himself in 1880 decried this as a system set up for “bankers… who are not chosen by the people… [but are] trusted with this great power involving the welfare and happiness of fifty million.” In fact Weaver would argue in that same Congress something almost Trumpian, railing against an “international conspiracy, inaugurated by men who had fixed incomes [rent-seeking].” In modern parlance: globalism.

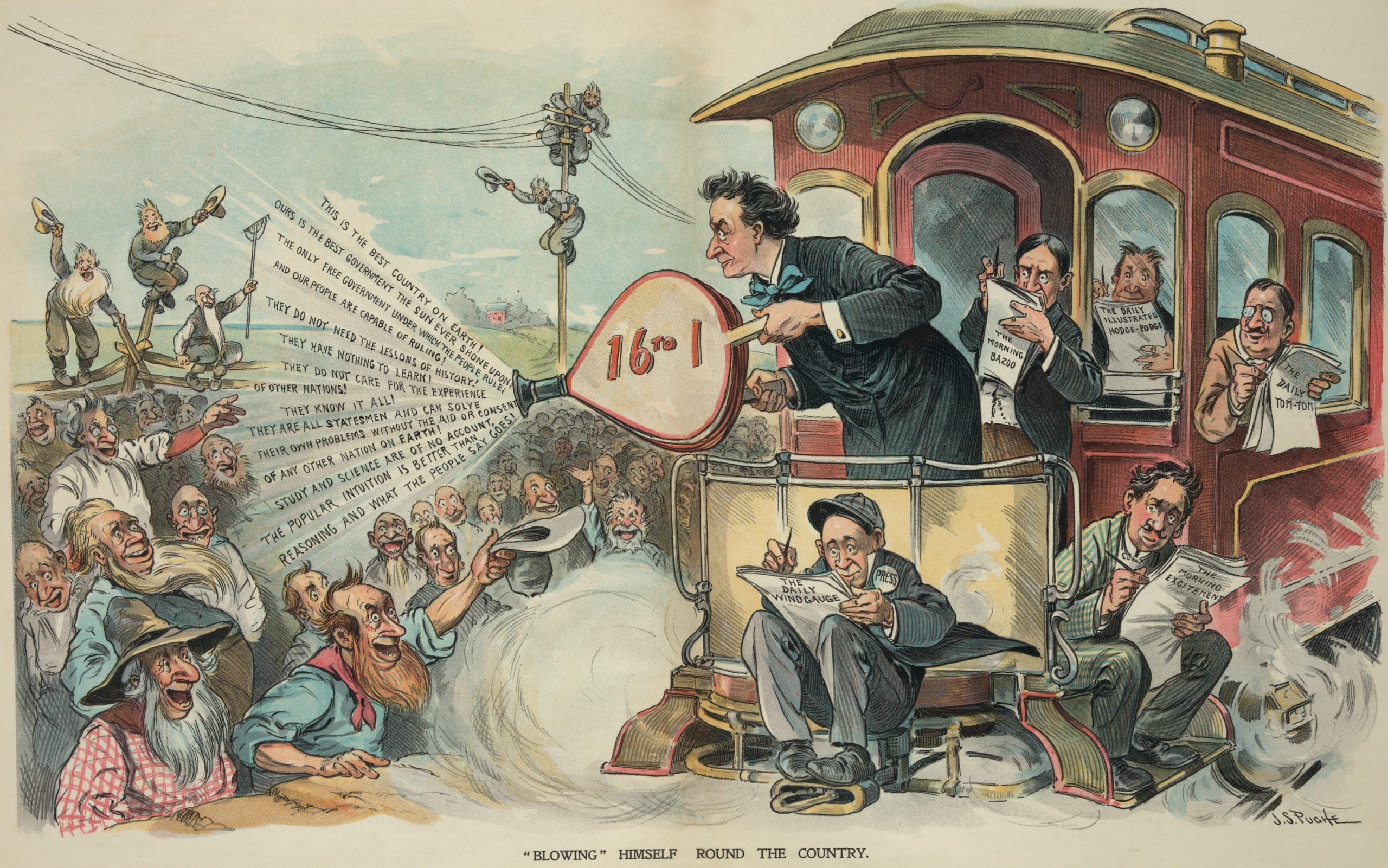

Leading the populists in 1892, Weaver campaigned vigorously on the issue of free silver against the gold standard and banking systems that were supported by both the Democrats and Republicans. He won 22 electoral votes, 5 states, and over one million votes as the most successful third party run since the Civil War. In 1896, Bryan ran a “fusion” ticket with the Democrats on the same issues, winning the nomination with what is arguably one of the most famous speeches in American history (the “Cross of Gold”). Though he lost the election, he would eventually become Secretary of State and influence policy there.

Bryan’s influence on Woodrow Wilson would result in the creation of the Federal Reserve and the removal of printing powers from state banks to the federal government. The gradual abolition of the gold standard did occur, ending finally in 1971 under Richard Nixon. Federal control over interest rates made it easier to set the price of debt, and the abandonment of the gold standard meant there was really no external limit to leverage capabilities. Large American companies borrowed and borrowed, while rural and working Americans paid off those debts their families had taken on in the early 1800s and accrued hard-earned family assets.

Then comes 2008. While farmers might have held debt in the late 1800s, it’s important to remember that the debts were relative: large for the farmer in question. The debts by 2008, however, were large in absolute terms, and now instead of individuals being indebted to corporate America, it was corporate America that found itself indebted. In 2008 large-corporate debt accounted to $6.6 trillion, roughly half of 2008 GDP (thanks in part to COVID, today’s corporate debt load is almost $10 trillion). What happened in 2008 when these companies couldn’t pay this money back proved correct John Maynard Keynes’s famous quip: “If you owe your bank a hundred pounds, you have a problem. But if you owe a million, it has.”

In September of 2008, Hank Paulson dropped to one knee and begged Nancy Pelosi to approve a $700 billion stimulus package to provide immediate liquidity to the American economy. She agreed. It’s hard to see what other option she had. But in that singular moment, the seeds of modern economic populism were sown. If the removal of silver was the crime of ‘73, for many rural and working Americans, this could be considered the crime of ‘08.

Why? Easy money is an indirect tax. If free silver and bimetallism would have placed this tax on those with assets to help those indebted, then the stimulus of 2008 (and continued iterations thereafter) did the same. Stimulus after all is just a fancy way of saying “printing money”. Only this time the “asset holders” and “indebted” had flipped. Now the rural and working American paid this tax, found that his savings account covered less than it used to, his paycheck did not go as far, and his small business couldn’t bring in enough money to keep going. The beneficiaries of this inverted Robin Hood transfer of wealth were large American multinationals, who were able to push off the looming debt disaster and keep their cash flowing.

What happened next is well known. The same accusations as were leveled in the 1890s emerged in the 2010s. Both Occupy Wall Street and the Tea Party (populist prototypes akin to the Greenbacks or the Knights of Labor) raged against a system set up for the benefit of elites in major financial centers to the detriment of those at the bottom. Ron Paul’s 2012 campaign caught fire not because of his stance on marijuana, but rather for his contempt for the Federal Reserve, with son Rand winning election to the Senate on a campaign pledge to ‘Audit the Fed.’ Similarly, by 2016, Trump adopted the stance of the populists: railing against the swamp and the DC acolytes who defended it. Probably unknowingly, The Donald wound up pegged to a movement with deep monetarist history.

The monetary proposals supported by modern populists are the opposite of the 1890s. Weaver and Bryan wanted easy money, as opposed to the Pauls and Trump who want to protect the value of the American dollar. The framework, however, is the same: a cabal in our nation’s wealthy power centers will construct a political and economic system aimed at entrenching wealth and power in those centers, and the Americans on the edges, those who toil in field and factory to build the country, be damned.

Whether the populists have, or had, a point, is to be determined by the reader. Perhaps the reader will conclude that the populists don’t know anything about economics. But one thing is undeniable: no matter how much American life may transform; some dynamics will never change. Perhaps we can say, then, that Weaver was correct when he lamented Congress’s seeming inability to set up any economic system that did not somehow create “a system of permanent national banks, a system of permanent national debt, and banks resting upon that debt.” Perhaps he knew that any such system was bound to lead to a reaction that he would be proud to champion.

Dylan Stevenson is a recent graduate in history and economics from the University of Notre Dame, having previously attended Harrow School in England, the country of his birth. He is presently working as a banking analyst in New York.