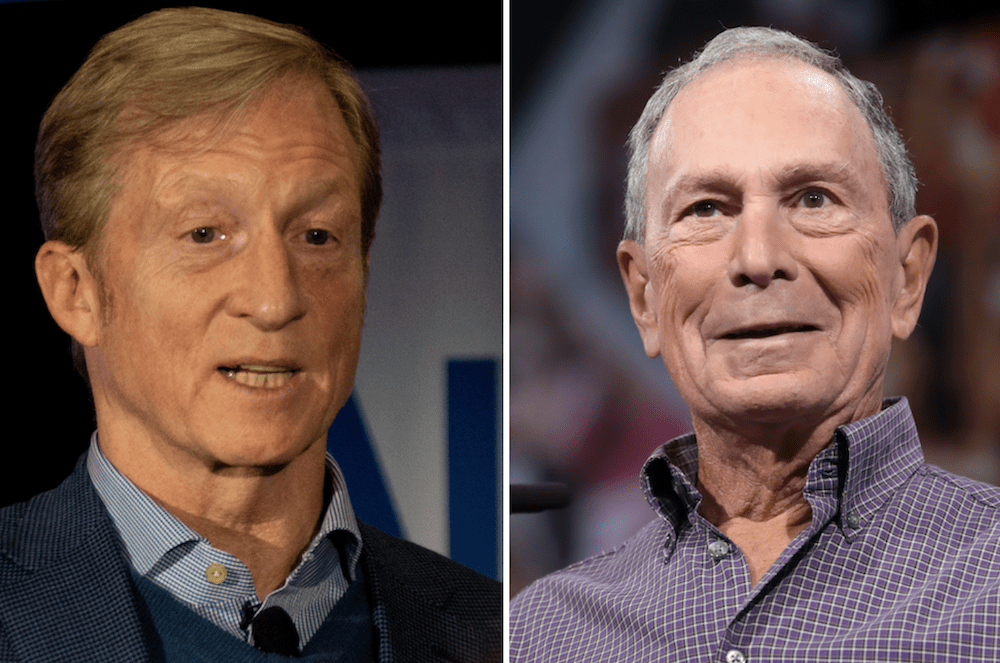

Bloomberg + Steyer = 2 Plutocrats Who Gambled on Voters, and Lost

Tom Steyer and Mike Bloomberg, two plutocrats who thought the presidency was just another acquisition. Now having spent nearly $1 billion between them on their failed campaigns—and maybe a lot more than that, as we shall see—they are a little bit poorer. But probably not much wiser.

Steyer and Bloomberg are both smart guys, but they might have done some due diligence, in the form of reading—or at least being briefed on—Max Weber’s well-known 1918 speech, “Politics as a Vocation.” If they had, they would have learned that, as Weber put it, politics “takes both passion and perspective.”

And by “passion,” Weber didn’t mean just lust for high office. As he put it, such egoistic greed is a “sin against the vocation” when it “becomes purely personal self-intoxication.” Instead, Weber meant that the successful politician must balance an “Ethic of Moral Conviction” with an “Ethic of Responsibility.”

No doubt Steyer and Bloomberg would say they had all that and more—after all, they paid good money for everything.

According to OpenSecrets, Steyer spent nearly $253 million—99 percent of it donations to himself—on his White House bid. But perhaps he really spent much more. Let’s not forget that back in 2013 he started an overtly political organization, NextGen America, aimed at raising green consciousness. Later, in the Trump era, he founded Need to Impeach, which is self-explanatory.

Both of these groups gave Steyer a national platform. In fact, they now look like the early phases of a well-lawyered presidential campaign, helpful at building name recognition, accumulating lists, and warehousing talent. Yes, these ventures no doubt made perfect sense as a presidential business plan. The only problem, of course, was that the product, Steyer, wasn’t very good.

As for Bloomberg, he reportedly spent $600 million on his formal campaign, although again, the real dollar total in pursuit of his political ambitions is surely significantly higher. In 2019 alone, Bloomberg’s charitable giving hit $3.3 billion; according to Tom Scocca of Slate, his goal was “buying goodwill and the silence of potential critics across the country.”

As an aside, we might ask: shouldn’t the Federal Election Commission be looking into all this? And the IRS as well? That is, if plutocrats can spend this kind of money on their proto- and actual campaigns, shouldn’t there be some sort of honest accounting? And that’s to say nothing of rigorous enforcement as to what is a charitable contribution and what is simply a political bet.

Interestingly, many of the usual “campaign finance watchdogs” have fallen silent; it’s been a while since most Democrats feared “money in politics.” These days, when big money is coming from the likes of Steyer and Bloomberg, aiming to smite Trump, they seem to want even more of it.

In the meantime, the two tycoons have discovered that money can’t buy everything.

If only they’d brushed up on their Max Weber. In his 1918 speech in Munich, the eminent German sociologist identified three kinds of “inner justifications” for political votaries.

The first of these, he declared, was “traditional,” as in the authority of the “eternal yesterday.” So merely being rich—especially the nouveaux riches of Steyer and Bloomberg—doesn’t fit the bill.

The second justification, Weber continued, was “charismatic”—and so for those two, we can stop right there. (To anticipate a question, here’s where Donald Trump squeezed into politics; in 2016, he was reviled by many, yet revered by enough to win.)

The third Weberian justification was “legal.” That is, “belief in the validity of…functional competence, based on rationally created rules.” Since Steyer had no political track record, there was no daylight for him there, and yet there might have seemed to be some for Bloomberg. After all, he had been mayor of New York for 12 years, and his supporters say he did a great job. Indeed, in the February 19 debate in Las Vegas, Bloomberg hit the competence theme hard, describing himself as a skilled “manager” no fewer than three times.

Of course, that was the very debate that sank Bloomberg, as Senator Elizabeth Warren repeatedly fired verbal torpedoes that hit him below the waterline. Indeed, political vocationalists were amazed that Bloomberg had no satisfactory shield, or evasive maneuver, against such predictable projectiles as his sexual harassment rap sheet and his tax returns. It does seem, in fact, that there’s a lot more to good politics than just spending money.

Once again we can look back to Weber, who declared that a successful politician must be seen as a “servant of the state”—and nobody who has watched Bloomberg for more than five minutes thinks that he sees himself as a servant to anybody or anything.

Moreover, both Bloomberg and Steyer should have recognized that they flunked Weber’s two prime prerequisites for successful politicians, the aforementioned “passion and perspective.” Both men wanted to be president—that was their passion, though it wasn’t what Weber had in mind. Indeed, the warped passion of their own naked ambition further warped their perspective. If a sultan hires enough viziers, they will tell him anything he wants to hear, yet proper perspective isn’t gained that way.

In the case of Bloomberg, his me-first perspective became blindingly visible at a campaign event on March 3, when in the middle of the coronavirus crisis, he grabbed a piece of pizza, tore off the crust, ate the rest, licked his fingers, then put the crust back in the pizza box. In other words, in less than a New York minute, he violated just about every public health protocol. Soon the video of his virus-friendly chow down went viral.

No doubt Bloomberg, and Steyer too, would say that whatever their flaws, they had more important things to say and do than were the province of ordinary politicians, such as, say, Joe Biden.

Indeed, the Bloomberg campaign repeatedly insisted that Biden, as well as the other “moderate” Democratic hopefuls, should step aside so that Bloomberg could take on Senator Bernie Sanders one on one, and so save the Democrats from socialism.

Needless to say, Biden, that dogged political veteran, chose not heed to Bloomberg’s advice—and so now it’s Bloomberg who has stepped aside for Biden.

A century ago, it seems that Weber had Bloomberg pegged as the non-politician he is: “Only he has the calling for politics who is sure that he shall not crumble when the world from his point of view is too stupid or too base for what he wants to offer.”

As for Biden, Weber seemed to get him right too: “Only he who in the face of all this can say ‘In spite of all!’ has the calling for politics.” In the Weberian reckoning, Biden the pol seems stoic, maybe even a little bit heroic—which is one reason why he’s on track to be the Democratic nominee.

We might add that while there’s a timelessness to Weber’s understanding of politics, there’s more than a little poignance to the time and place of his address.

Weber was speaking just two months after the old German political order—that of the Hohenzollerns and the Prussian Junkers—had collapsed alongside Germany’s defeat in World War I. Into that political vacuum came communists and Nazis, even as well-meaning Germans struggled to create a viable democratic republic. In his academic way, Weber was attempting to teach his audience what normal and healthy politics might look like.

Sadly, soon afterward, in 1920, Weber died of—more poignance—the legendarily lethal worldwide flu pandemic. He was only 56. Thus we are left to wonder if Weber’s steadying conservatism could have helped stave off the bleak fate that befell Germany’s Weimar Republic.

So now back to the USA a century later. As we have seen, Bloomberg and Steyer have no place in elective politics, and yet interestingly—and perhaps ominously—Bloomberg seems to have gotten the political bug. While still in the race, his campaign had pledged to “spend Trump out of office.” And now that he has dropped out, Bloomberg declares himself to be just as determined: as he said in his March 4 farewell to his Manhattan campaign staff, “I entered the race for president to defeat Donald Trump, and today, I am leaving the race for the same reason: to defeat Donald Trump.”

Though come to think of it, Bloomberg isn’t saying “farewell” at all, at least not financially. Reports have it that he is simply going to shift his campaign, at his own continuing expense, over to help Biden. In other words, Bloomberg seems to have gone from self-funding his campaign to self-funding much of Biden’s campaign.

Legal sticklers have asked if such a resource shift is legal. Quite likely, Team Bloomberg will re-cross enough T’s and re-dot enough I’s to make everything fine. Besides, if the Federal Election Commission (FEC) can’t be bothered to adequately account for all of Bloomberg’s (and Steyer’s) political spending over the past few years, it’s a safe bet that the FEC isn’t going to do anything about Bloomberg’s spending in the next eight months.

In other words, Bloomberg is going to spend whatever it takes to keep himself in the political spotlight. To be sure, if he spends a billion, or more, to help Biden, he can expect to remain a continuing target of Trump’s tweets—and he seems to welcome the attention, as well as the accompanying opportunity to tweet back.

For instance, Bloomberg equated himself to the saintly Obi-Wan Kenobi from Star Wars—and, of course, cast Trump as Darth Vader. No doubt, in the weeks and months ahead, there will be many more mogul media melees.

Of course, there’s still the basic Weberian problem, namely that Bloomberg isn’t an attractive politician—or ally. Thus should the billionaire insist on being a prominently visible presence in Biden’s campaign, it could only give Trump another target with which to hurt the former vice president’s chances in November.

Moreover, we can be sure of Bloomberg’s continuing lust for the presidency. He might never understand the Weberian ideal of the political vocation, but he no doubt still sees politics as a financial proposition.

So if something bad were to happen to Biden in the next few months—such as, say, one of his anecdotes falls into anecdotage and can’t get up—it’s possible that the 3,979 delegates convened at the Milwaukee Democratic convention could find themselves in a political bazaar. If so, expect many presidential wannabes, new and old (here’s looking at you, Hillary!), to enter the souq, haggling for the deal of a lifetime.

Or maybe the convention will be more like an auction house. If so, Bloomberg the big spender will be ready.

He might not be much of a pol, or even much of a Democrat, but as a plutocrat, Bloomberg’s credentials are sound. And a billionaire always knows how to make a high bid.

Comments