The “Reclaim Her Name” Project Is a Bad Idea

“This week, with much fanfare, the Women’s Prize for Fiction, together with its sponsor Baileys, unveiled, as part of the prize’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebrations, a ‘Reclaim Her Name’ project: twenty-five novels whose women authors were originally published under male pseudonyms, now reissued with the author’s ‘real’ or non-pen names, displayed on covers designed by a host of international illustrators, also all women. Available to download as e-books, with physical boxsets being supplied to libraries, the project, according to Bailey’s and the prize, is ‘finally giving female writers the credit they deserve’.” It’s a bad idea, Catherine Taylor argues in the Times Literary Supplement:

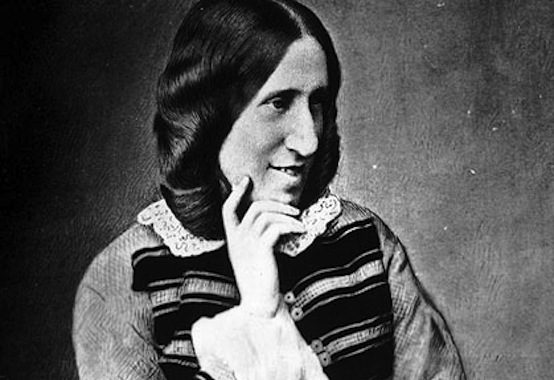

Does George Eliot, whose Middlemarch is featured here, really need ‘reclaiming’ as Mary Ann Evans? The ‘Reclaim Her Name’ bio glibly states that Eliot was ‘forced to use a male pen name’, as if she were incapable of making her own decisions. ‘George Eliot’ was Evans’s public persona, with, surely, no need for retrospective correction. By the time Middlemarch was published, the reading public was fully aware of its author’s real identity. Besides, by 1871/72, when Middlemarch first appeared in instalments, the name she was known by was Marian Evans Lewes, as the common-law wife of her partner George Henry Lewes. According to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ‘Mary Ann’ was not used by Eliot from 1851 until 1880, the last year of her life, when she chose ‘Mary Ann Cross’ on her marriage to John Walter Cross. Intentions matter, but so does legacy. Is it really for others to speak for Eliot/Evans and designate a different agency?

In other news: Identity politics, by definition, deals in stereotypes. One becomes this or that to the degree that one shares certain characteristics—characteristics, often, that are mere constructions. It is a false and oppressive way of thinking and has no place at the university. Laurent Dubreuil explains in Harper’s: “Whereas identity politics, as theorized four decades ago, aimed to liberate the oppressed and to oppose American capitalism, its main form today is more invested in changing the direction of domination and in multiplying restrictions. It is the social order of the day, its rhetoric ubiquitous in the neurotic centers of the American economy (universities, the media, the tech sector). Under this regime, identities, once affirmed, are indisputable. If I say, ‘As an x, I think. . . ,’ I am no longer voicing an opinion that can be evaluated or critiqued within a shared space of discourse; I am merely saying what I am. If you disagree with me, you may trace everything I say back to my identity before availing yourself of corresponding counterarguments: you say a because you are an x, but I am a y and I therefore believe in b. Such identities, I insist, are not emancipatory, neither at the psychological nor at the political level. We all should have the right to evade identification, individually and collectively. What’s more, identity politics as now practiced does not put an end to racism, sexism, or other sorts of exclusion or exploitation. Ready-made identities imprison us in stereotyped narratives of trauma. In short, identity determinism has become an additional layer of oppression, one that fails to address the problems it clumsily articulates.”

Watch a 1902 film clip of Wuppertal’s flying trains: “The city is known still today for its schwebebahn, which is a style of hanging railway that’s unique to Germany.”

“Bring back the great British holiday camp,” Steve Morris writes. It offers “exactly what we need today: simplicity, gentle fun and sense of community.”

In praise of the textbook: “For 150 years, the textbook was a mainstay of American classrooms. Their progenitor was the McGuffey Readers, of which an estimated 120 million copies were sold between 1836 and 1960. Written by frontier teacher and scholar William Holmes McGuffey, the original Readers contained literary selections that promoted Calvinist ideas about salvation and piety, while later editions were secularized in keeping with the nation’s changing mores. These days, the Readers are better known for their role in shaping American identity and culture than for how they changed teaching and learning. But although they seem stuffy and moralistic to contemporary eyes, the Readers represented an important pedagogical step forward in their time and spoke to the real needs of students McGuffey witnessed, first as a roving teacher who began working in schoolhouses at age 14 and later when he tested his textbooks with groups of neighborhood children in Ohio. The Readers were organized into levels across which students would progress over time, from phonics, through basal stories, all the way up to selections from Milton. Vocabulary was taught gradually by repeated exposure to words in context instead of being doled out in a list for memorization. Unlike their predecessor the New England Primer, which was designed to put the fear of God into children, the Readers were designed to be appealing to children, and incorporated helpful, clear illustrations.”

Another day, another cancelation. The University of Oregon to cover up four murals with aluminum panels.

Roger Scruton’s architectural morality: “Some of the his most under-appreciated contributions are on the relationship between everyday life and the built environment.”

Photo: Beyenburger Klosterkirche

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.