Business, Government, and Cheap Debt

In a recent FT column, Lawrence Summers argued that “governments that enjoy [today’s] low borrowing costs can improve their creditworthiness by borrowing more not less.” He ended his column by writing, “Any rational business leader would use a moment like this to term out its debt.” Contrary to Summers, I will argue that a rational business in anything like the financial position of the world’s major governments would cut spending immediately, in order to rein in massive deficits.

Now in fairness to Summers, he makes some technical arguments involving negative real interest rates, and he is careful to restrict his case for deficit-spending to projects that “reduce future spending or raise future incomes.” With a generous interpretation, Summers’ argument reduces to a tautology: we could take him to be saying that if a business found that it would be profitable to take on more debt, then a profit-seeking business would do so. Yes, that’s true as far as it goes, but it doesn’t at all follow that the United States and other governments today, ought to be taking on more debt. Summers’s analysis focuses on a few technicalities while ignoring the elephant in the room.

First, it’s significant that private business has not, in fact, been running up massive debt, even with record-low interest rates. It’s true, businesses do not enjoy quite the low yields that the U.S. government gets on its Treasury securities, but the average borrowing cost for AAA corporations is nonetheless at a 50-year low.

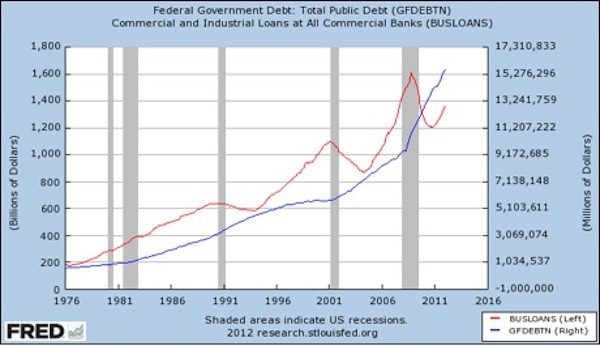

Even though both the federal government and the private sector are currently enjoying the lowest interest rates in half a century, look at how differently they have behaved regarding their indebtedness during recessions:

As the chart above makes crystal clear, in the midst of a recession business borrowing from the commercial banks either stagnates or drops sharply, while federal debt marches steadily upward and often accelerates. It’s true that the red line above captures just commercial and industrial loans from commercial banks, but even a broad measure of total nonfinancial business debt shows a similar pattern—it fell when the latest crisis hit, and has only gradually recovered.

When discussing the alarming trajectory of the government’s debt, it is typical to use the measure of the federal debt “held by the public” (i.e. netting out the Treasury securities held by government agencies) and then dividing by Gross Domestic Product. This popular figure, often summarized as “debt/GDP,” was at a modest 33 percent in 2001, after the Clinton Administration actually ran a few budget surpluses (at least according to the cash-flow accounting that is typical in DC). Yet after the disastrous profligacy of first Bush and then Obama, by 2011 the debt/GDP ratio had more than doubled to 68 percent. Worse still, the Congressional Budget Office projects that if Congress continues to take the path of least resistance on issues such as the Alternative Minimum Tax and the “doc fix” (i.e. the Medicare reimbursement rates for doctors), then in another ten years the debt/GDP ratio will be 93 percent.

Grim as these figures are, they are too optimistic when it comes to Uncle Sam’s true position. Most people reading the above commentary might think, “The rapid growth of federal debt in just a short time is a bit disconcerting, but in the grand scheme of things a debt-to-income ratio of 68 percent right now isn’t that awful…”

Yet this is all wrong. We shouldn’t accept the premise that the government owns the entire economy; hence “GDP” should not be considered the government’s “income” in a given year. If we’re going to pick a specific number, the proper analog would be federal receipts. In 2011, the total federal debt held by the public was just about $10 trillion, while federal receipts were $2.3 trillion, for a debt-to-income ratio of 433 percent. That is a much more astonishing figure, especially when we consider that this is largely unsecured debt (i.e. it’s not as if Uncle Sam used the borrowed money to build a factory) and that it also ignores the many trillions in actuarial debt embedded in Social Security and Medicare.

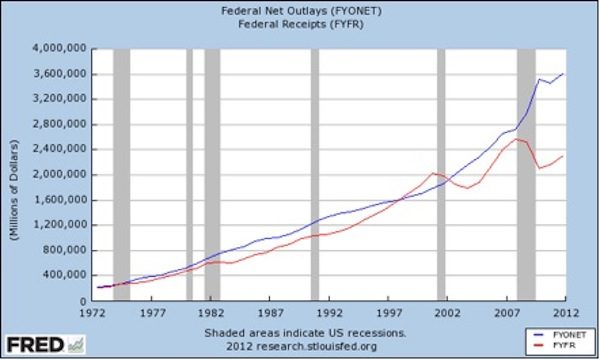

Now to be fair, an apologist for more federal deficit spending might point out that receipts are depressed right now because of the severe recession, and so my figure of federal “debt-to-income” of 433 percent might fall once the economy recovers. Yet even if we go this route, it still supports my main point, namely that the feds have not at all been operating the way a private business would. Let’s look more closely at the trends in federal spending versus receipts since the crisis struck:

In the chart above, the blue line shows total federal outlays while the red line shows total federal receipts. If the CFO of a private corporation showed the above chart at a shareholder meeting, would the audience demand to know—a la Larry Summers— why the corporation had been so timid about taking on more debt, in light of record-low borrowing costs? Is that really the take-away message from the above chart?

Thus far I have tried a few different arguments to underscore that the private sector in general has not been behaving the way Larry Summers suggested it would, and also that the federal government’s position would call for massive austerity if it were a corporation.

Yet there is an important sense in which Summers’s analogy fails, beyond these points. Even if it were true that a private corporation would take on more debt, if it were currently wearing Uncle Sam’s shoes, that alone wouldn’t be sufficient to seal the argument. This is because government debt involves present citizens living at the expense of future taxpayers, who may not even be alive yet to argue about the decision.

Earlier this year, Keynesian economists such as Paul Krugman and Dean Baker tried to pooh-pooh the layperson’s reluctance to “saddle our grandkids” with a large government debt. Krugman and his allies rolled out the familiar claim that collectively the federal debt isn’t really a burden because “we owe it to ourselves.” Yet Krugman et al. were simply wrong. This is yet another example of very smart people using sophisticated arguments to convince themselves of something that common sense tells us is balderdash. Yes, deficits today do involve an effective transfer of wealth from the future into the present. The mechanism is subtle, and I explain the intuition here. But the effect is nonetheless real, meaning that the man on the street is perfectly correct when he says that government should live within its means, both for economic and moral reasons.

Larry Summers and other apologists for larger government debt can continue coming up with clever arguments, but they can’t evade the basic truth: in a time of recession, when all other institutions in the world are watching every penny and eliminating unnecessary spending, the government should too. Indeed, even some projects that are “worth it” during boom times should nonetheless be axed during a severe recession when tax revenues have plummeted. This is exactly what a private business would do.

Robert P. Murphy is author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Capitalism. His blog is Free Advice. Follow him on Twitter.