What New York Doesn’t Understand About the ‘Far Right’

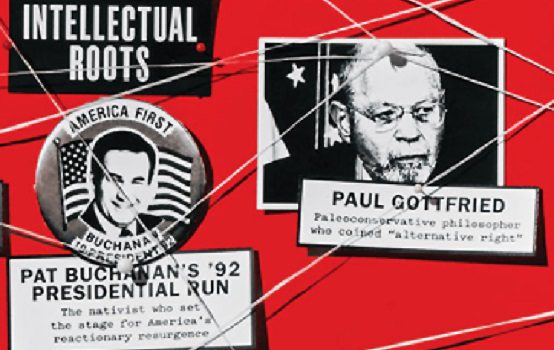

New York magazine has just run a feature entitled “Beyond Alt: The New Reactionary Counterculture,” giving recognition to what is called “the most potent political movement of our age.” In a summary on the inside cover, we learn that the movement in question is one “that helped Trump get elected (but is already restless); encompasses both techno-libertarians and those who wish the Enlightenment had never happened; provides harbor for racists but also gay grads; and speaks ominously the language of the young.” Because we subscribe to New York (mirabile dictu!) I immediately opened to the article in question. There I noticed several unflattering pictures of me, one of them wedged in between photos of Jared Taylor and Steve Sailer. I also found a description of me as a “nativist strategist” and as someone “who spent a career agitating for an ethno-nationalist conservatism that celebrated Western white values and lamented what feminism and multiculturalism had done to dilute them.” It was also mentioned that I was “perfect for Pat Buchanan whose 1992 presidential campaign he advised.”

Since a photo of Pat Buchanan addressing a convention is shown on the same page with my picture, tying me to Pat, whose 1992 campaign I did advise, may be justified. Presumably I was “perfect” for that campaign because the worldview attributed to me was one that Buchanan promoted during his presidential campaigns. All the same, I don’t recall Buchanan running on a “white Western value” platform, although I do remember that he opposed abortion, believed in restricting immigration to people who would fit in culturally as well as economically, and—like members of both national parties at the time—was not keen on the gay agenda.

As for me, I can’t understand how my work of almost 50 years amounts to a “nativist strategy.” Most of what I’ve published is scholarship on various historical subjects and hardly a strategy for promoting whiteness or ethno-nationalism. What I have argued when writing political polemics is the following: States that are culturally homogeneous tend to be more stable than those that are not; multiculturalism is a means by which certain elites can generate ethnic and social problems that they then put themselves in charge of and from which they derive benefit. Moreover, multiculturalism is a quintessential political religion, in that it offers moral and spiritual redemption through revolutionary change under the direction of an all-powerful political class. I’ve also mocked the view that whatever American “liberal democracy” and the post-Western “West” have become at this point in time should be a model for universal conversion. The American government should not be running around the globe forcing on others our latest version of “democratic” enlightenment.

The editors of New York may disagree with my priorities and analyses, but I don’t see how this disagreement proves that I’m a white nationalist. Yet their depiction of me may be characteristic of the careless way in which some of the contributors approach their work. They indiscriminately throw together thinkers and activists with whom they disagree and then provide an “inclusive” demonological narrative. What do “techno-libertarians” and “gay grads” have to do with Pat Buchanan, Steve Sailer, West Coast Straussians, or me, other than the fact that some or all of us have been relegated to the right of an extremely restricted conservative establishment? What is the instructive value of juxtaposing Catholic traditionalists with gay white nationalists? What do the two have in common, other than being equally offensive to the authors? The term “reactionary counterculture” is made to serve the same imprecatory function here as does the word “fascist” for the anti-Trump left and neoconservative journalists. It means bad people whom we are urged to shun.

Of course the featured theme could have been developed more coherently if the editors of New York were interested in doing so. Unfortunately they seem intent on lumping together all their villains and linking them, however circuitously, to The Donald. That may be an illustration of the distinction between advocacy journalism and a scholarly inquiry. (Clearly most of the contributors weren’t engaged in the second.) That said, there is an essay by a certain Moreen Malone that makes several good points.

The alt-right, according to Malone, represents a youthful revolt against the “pieties of the ‘Establishment Right,’ starting with ‘corporatism, taxes, cultural inclusiveness at least at the rhetorical level.’” Malone believes, however, counterintuitively, that alt-right bloggers succeeded in refocusing the GOP during the last presidential race on those “uglier and often unofficial aspects of the GOP platform that had been used for decades to appeal to the ever-poorer and less-educated base of the party.” But it’s unclear how the alt-right did this, given that the GOP-neoconservative media have worked overtime to marginalize it. Malone also casts doubt on her own claim when she tells us that “54% of Americans haven’t heard of [the alt-right].” Finally, Malone doesn’t explain how Trump’s platform appealed to our baser natures: Is she referring to Trump’s willingness to enforce our immigration laws?

Yet Malone also points out that the alt-right may be indicative of a “new reaction” that is sweeping Europe and emphasizing historical identities in reaction to globalism and multiculturalism. She contends that Western and Central European parties of the right reflect most of the same concerns being raised by the American right-wing counterculture. Resisting and if possible deporting culturally alien and sometimes riotous Muslim immigrants from the Third World, preserving what is Western about the West, and attacking globalist elites are the shared attributes of European parties that American journalists characterize as “far right.”

One also sees a sharp difference in the U.S. between the “establishment right” and the right-wing counterculture in how they react to such European figures as Marine Le Pen and Vladimir Putin. The establishment hates both figures, and neoconservative journalists have quite emotionally thrown their support in the French presidential race to “moderate centrist” (read: cultural-social leftist) Emmanuel Macron against the “ultrarightist” and “anti-Semite” (read: French nationalist Catholic) Marine Le Pen. While the establishment inveighs against Putin as the adversary of gay rights, those further on the right applaud him as a counterrevolutionary.

Another point that New York gets right concerns the wars and purges that have convulsed the conservative establishment since William F. Buckley created a “conservative movement” in the 1950s. In a staggering understatement, National Review Senior Editor Jonah Goldberg asserted in a commentary commemorating the 50th anniversary of the founding of his magazine: “Buckley employed intellectual ruthlessness and relentless personal charm to keep that which is good about libertarianism, what we have come to call ‘social conservatism’ and what was necessary about anti-Communism in the movement. This meant throwing friends and allies off the bus from time to time.” Goldberg was referring here to what has become a continuing battle against dissenting voices in the authorized conservative movement. Those driven out of the NR community in the 1950s and 1960s were mostly libertarian critics of Buckley’s Cold War zealotry and were dismissed with a certain gentle regret. But later, and increasingly after the neoconservatives gained power in the conservative movement, the épurations were turned against right-wing dissenters. Once that began to happen, those who were expelled found their “conservative” detractors sometimes continuing to injuring them professionally.

It’s hard to examine the non-authorized right objectively without noting these conservative wars. New York does mention at least one minor incident in these prolonged conflicts. It recounts how Rich Lowry became National Review’s editor-in-chief in 1998 because his predecessor had favored immigration critics more than his aging boss Buckley wanted him to. Since the 1980s, Buckley had fallen under the spell of a largely neoconservative social circle in Manhattan, and he tried to push his fortnightly in their direction. In the 1990s, Norman Podhoretz and his wife Midge Decter expressed anger at the way Lowry’s predecessor, John O’Sullivan, had given space in his magazine to immigration restrictionists, and this may have provided the immediate cause for demoting O’Sullivan to some kind of roaming editor.

There was a certain irony in all this. Ten years earlier, on a ride in my car to Richard Nixon’s home in New Jersey, where both of us were invited to dine, O’Sullivan seemed confident about his recent appointment. He assured me that he knew how to perform “the balancing act.” He would keep “Norman and Midge” on his side while opening his magazine to certain controversial subjects. Obviously he misjudged badly. O’Sullivan’s successor has been more circumspect about defying those who control his professional future.

Paul Gottfried is the author of Leo Strauss and the American Conservative Movement.