What Is A Nation?

A liberal friend e-mailed to say that he is bothered by my support for Hungarian PM Viktor Orban. I responded to ask what, specifically, bothers him. I told him the media reporting on Orban and Hungary is for the most part bad, and misleading. Maybe, I said, there really is something substantive about your concerns, or maybe you have been mislead by the reporting. He said that he grew up in a foreign country, when the political climate was rife with "ethnonationalism," and that scares him about Orban.

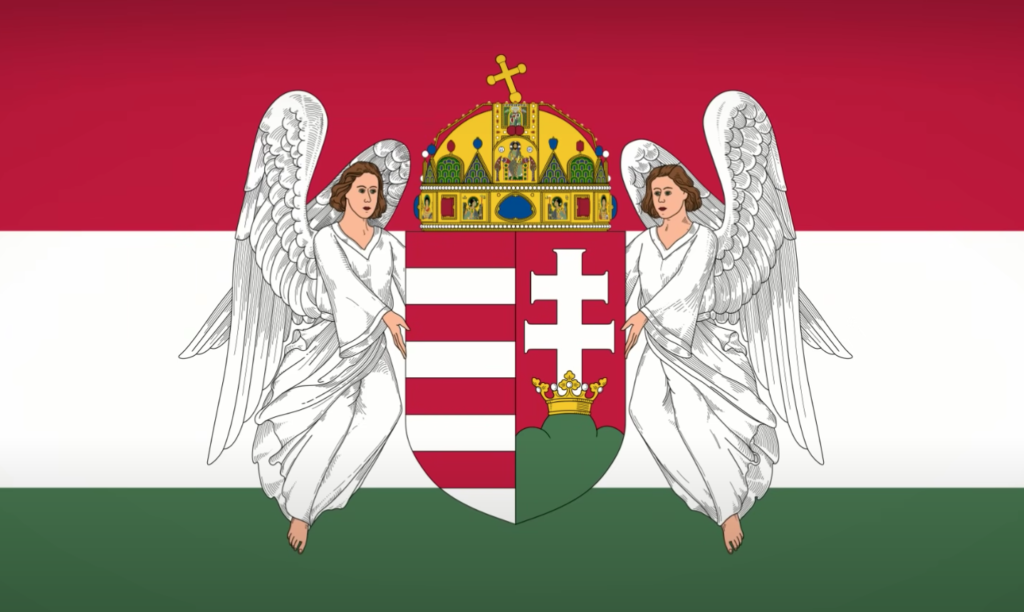

I responded by sending a link to Orban's speech, so he could read the PM's comments in context. I told him he might still disagree with them, but that he should be clear that Orban was not talking about Magyar supremacy, but about Islamic immigration to Europe. I mentioned to my friend that he might find that objectionable (he's a liberal, after all), but that the clash between Christian and Islamic culture has defined Europe since the Muslims invaded Spain in the 8th century, only ending with the final defeat of the Ottomans at the gates of Vienna late in the 17th century. Besides, he should consider that the Hungarians (and the Poles, for that matter) look at the huge and unsolvable mess that the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Belgians, the Swedes, and other have created for themselves by importing huge numbers of unassimilable Muslim communities in the last century. As a practical matter, why would these European countries who don't have these problems now want to create them? It's not a question of one civilization being superior to another, but rather of them being so different that an attempt to blend members of these civilizations into one is really difficult.

My friend and I agreed to talk about it later by WhatsApp. But that question came to mind again when I clicked on a Twitter link to this 2021 TAC essay by Darel Paul, musing on the question of nationhood. He writes:

Every debate is afflicted by a confusion of terms, but the debate over American national identity is cursed seven times over. Does the United States even constitute a “nation”? In the sense of common descent (the root of “nation” is the Latin nasci, to be born), clearly not. Widespread fear of such an ethnic sense of American identity drives considerable hostility to the very idea of nationalism. Most American elites prefer words like “patriotism” (never mind the Greek root patrios, of one’s fathers), a shared love of the law rather than a shared love of a people. The well-worn American creed, a belief in deeply American and yet simultaneously universal principles of liberty, equality, individual rights, and self-government, is offered as both the means and the object of this patriotic love binding the plures into an unum.

The problem with this conception of patriotism is that it is a weak glue. The recent history of the United States offers ample evidence. Rather than objects of agreement, liberty, equality, individual rights, and self-government are instead the objects of discord. The advance of one definition of equality is necessarily the violation of another definition of liberty (viz. the current political struggle over religious freedom). Even rival definitions of equality battle against one another in a zero-sum game (viz. the current equality versus equity debate). The expansion of individual rights as a solution to conflict has not only proved no solution at all. It throws more and more of the republic’s common life into the courts and the private realm, leaving less and less to be governed in common and thus shared in common.

Thus the understandable anxiety of American conservatives who are the loudest in proclaiming the limits of diversity beyond which no political community can survive. The problem with conservative complaints is that no one knows exactly where the American Rubicon lies. The left, in condemning unifying projects like “a city upon a hill” and “the melting pot,” implicitly suggest the line is exceedingly far away. Some centrists argue that national unity has always been a myth and, outside the brief era between Pearl Harbor and the Watts riot, strong divisions of cultural and political values have been the norm. Nevertheless the republic persisted.

How much unity does a political community even need, then? The question is meaningless in the abstract. Needed for what? The standard answer is civil peace. Without unity, so it is claimed, a polity is bound to descend into factional violence. Indeed, contemporary levels of political and civil violence in America are worrisome. Yet Scotland has been governed by a secessionist party for fifteen years without an outbreak of factional bloodshed. Flemings and Walloons have lived largely separate and parallel political lives for decades without even a hint of a Belgian civil war. Moreover, excessive demands for unity can themselves provoke violence, as happened in Spain in 2017.

Prof. Paul goes on to claim that imperial expansion is the only thing that really holds America together:

It is this promise of greatness, this glory of the expanding republican empire that knows only the boundary of the earth itself, that has been the glue of America. Because the United States is not a nation in the European or even Asian sense, common descent, common religion, and common culture bind only parts. That common glory of imperial expansion, combined with a republican form of government through which all citizens secure it and share in it, binds the whole.

I don't want to argue with the claim that imperialism is what binds us. It instinctively strikes me as off, but I'm not interested in thinking about it right now. What jumps out at me is the statement that the US "is not a nation in the European or even Asian sense." What he means is that we did not descend from a tribe. At one point in US history we might have decided that we were a European nation, and chose to follow an immigration regime that maintained that. But we didn't, so here we are today. There is no going back, even if you wanted to (and even then, how would you characterize Latinos, who unquestionably are descended from Europeans?).

That said, I believe that it is possible to bind the nation with shared values, though "values" is a feeble concept compared to "religion," "ethnicity," or "culture". But what else do we have? Though I have serious doubts about the viability of liberalism going forward, the reason I recoil from fellow conservatives' giving up on it is that I cannot think of any other political system under which a wildly diverse nation like America could be governed. The Left going all-in on racial identity politics is guaranteed to bring about civil conflict. I mean, what the hell is this about?

Here is a case of the Left giving up on liberalism, in favor of racialism. The incredible thing is that so few people on the Left see what they're doing. They are so blind because the kind of white people they surround themselves with are like the kind of white people who run most establishment European political institutions: filled with self-doubt, to the point of self-hatred, and unwilling to defend either themselves or a system striving to give people of all races equal opportunity (not outcome).

The other day, this blog's reader Hector St_Clare (the pseudonym of an academic of South Asian ethnicity) wrote in this space that Americans are quite naive about how the rest of the world sees itself, in terms of ethnic community and solidarity. What Viktor Orban had to say was not at all unusual in the rest of the world, Hector said. So, when I read this line from Prof. Paul -- "Widespread fear of such an ethnic sense of American identity drives considerable hostility to the very idea of nationalism" -- I understand why it is that we Americans flip out when we hear a remark like Viktor Orban's. Given the history of racist violence in the American South, I don't think it's wrong to be attentive to this stuff. But I do think it's silly for us Americans to think that we have this all figured out, and that anyone from elsewhere in the world who doesn't embrace American-style deracination is basically Hitler, Jr.

If you tell people that in order to be decent human beings they have to surrender any claim of loyalty to their own kind (to their tribe, to their co-religionists, to their cultural traditions), and even surrender any claim on the land where they and their ancestors live, you should not be surprised when they tell you to go to hell. These loyalties are felt so deeply that for most people, they are pre-political. If by "not liking ethnonationalism," you mean that you don't like it when political leaders rile up their fellow ethnics for the sake of war with other tribes, or oppressing minorities living among them, then I'm totally with you on that. But if by "not liking ethnonationalism" you mean that any expression of preference for your tribe (religion, culture, etc) as a basis for politics and solidarity is forbidden, sorry, I can't go there. Who are we to tell the Mexicans that they are wrong to want to keep their land and their culture dominated by Mexicans? Or the French, French? Or the Georgians, Georgian? In that sense, "ethnonationalism" is a redundancy, isn't it?

Maybe Prof. Paul is right. The last time I felt a strong sense of unity as part of the American nation was on September 11, 2001, and its immediate aftermath. And yet having lived through what America's leaders did with that sense of unity, and what I personally allowed myself to support (the war) out of a sense of national solidarity, and solidarity with the dead of 9/11 -- well, I fear making a strong claim on that again. However, if America were once again attacked so spectacularly by terrorists, I would probably feel that old, natural urge to solidarity.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Or would I? I can tell you that I would also be very, very suspicious of the way American leaders would manipulate that solidarity. And I would also wonder what kind of country had been attacked -- this, in a way that was unthinkable after 9/11. That is to say, so many of the most basic aspects of life in America, and fundamental American values, have been under radical assault over the past two decades that it is harder than it should be to say that we are a nation in any sense but nominal. I mean, look, we now have a social and political order dedicated to training children in many public schools, and in various manifestations of private life (e.g., media), to think that they might be the opposite sex, and need to have their bodies surgically and chemically altered. This is an evil thing to do to children, but this is considered not only good by many people who run this country, but is considered so good that anyone who opposes it must face the force of the federal government.

What ties bind people who think this is evil to those who think it is good? To press the point, are the ties that bind us stronger than the revulsion we have for each other?

Viktor Orban looks at how we are ruining our children with gender ideology, and turning ourselves against each other, and wants no part of it for the nation he governs. Can you blame him?

- "Ethnic" or "Tribal" nations. Those are nations that define themselves mainly through kinship. This is the case of the younger European Nations (the Germans, the Hungarians, the Slavs, the Norsemen) whose nomadic roots aren't historically remote.

In Asia, Japan is one prominent example.

- "Cultural" nations.

Those are nations whose bond is a shared culture and historical heritage. It's the case of the most ancient nations in Europe, such as Italy and Greece and, partly, of France, Spain and Britain (because of the implant of Franks, Visigoths and Saxons - Nations of the first kind - on the Celtic stem).

Those are the Nations that have built great civilizations and empires. In Asia, examples are China, Persia and India.

- "Political" nations.

Those are nations that define themselves according to a common set of artificial political stipulations. This is typical of former colonies, and most of the American Countries are of this kind, even though mesoamerican nations have a strong influence from large Indio populations, which used to be Nations of the "cultural" kind. But Canada, the US, Brasil, Colombia and Venezuela, Chile are definitely of such a kind.

It's interesting to mention France here, because it is a rare example of a Country that made a conscious effort to move from an admixture of Type I and II to Type III, with mixed outcomes at best.

The USSR tried a similar attempt but, as we know, it failed.

In general, nations of Type III are both troubled and troublesome, because of their lack of internal cohesion and their strong ideological nature. In such nations, ideology and myths (The "Founding Fathers", "Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité", "Communism", "El Libertador") replace the lack of family ties and of a common history and culture. France is maybe an exception, since it is caught in the middle of a tearing rejection of its roots.

The same problematic concept, replacing family and culture with an empty set of artificial "values" is the basic issue with the EU.

"Cultural" and "Ethnic" nations should be wary of "Political" nations and of their toxic ideologies..

And the US is a nation, and not just politically. There is such a thing as American culture and that is what unites us (yes, yes, one can find plenty to complain about in that culture!) But we are not just united by a political ideology as some would have it.

The problem with Islamic migration in Europe is not that the immigrants are not close genetic kin to the Europeans (in the larger sense Middle Eastern people are quite akin to Europeans-- more so than West Africans or East Asians-- the two regions have seen plenty of gene flows since prehistoric times). The problem is the cultural friction. But culture is learned. The child of two Iraqis, raised from infancy in Budapest by Hungarian parents, would be wholly Hungarian after all.