What Exactly is ‘The West’?

Every autumn, I have the great pleasure of teaching what we at Hillsdale College call “Western Heritage.” It’s the first core course that every entering student must take. With classes ranging from 15 to 20 students each, we read primary sources, ranging from Genesis to Plato, Aristotle to St. John, Cicero to St. Augustine, and Thomas Aquinas to John Calvin. Though I’ve been teaching this course since the fall of 1999, I have never once found myself bored or tired or uninspired. Quite the opposite, actually. Whatever my faults, this course has made me a better person and a better thinker. And, judging by how my students embrace the material, the same is true for them.

Yet, every fall, as I prepare for the class, one question lingers. It’s a question I’ve never been able to answer to my own satisfaction. What is the West? Ever since the “politically correct” movement began in the 1980s in the United States, its critics have complained of it—from a quiet seething to outright brutality and invasive protests—as racist, sexist, and imperialist. The critics can be as emotionally violent as they are intellectually dull.

In the 1980s, at least, even its critics took a canon of authors and texts seriously, asking only that the canon be more inclusive in terms of race and gender. Frankly, I miss those days. Today, at the vast majority of schools and colleges, the West is something hideous and embarrassing, to the point that the term itself can trigger almost automatic hatred and dismissal.

Let’s leave the critics aside from now, with one important caveat: a recognition that they’re simply wrong.

Even the terminology suggests much good. In much of the ancient Mediterranean, the West was the land of the gods, known as the Blessed Isles, the Blessed Realm, or, of course, Atlantis. Plutarch wrote:

These are called the Islands of the Blest; rain falls there seldom, and in moderate showers, but for the most part they have gentle breezes, bringing along with them soft dews, which render the soil not only rich for ploughing and planting, but so abundantly fruitful that it produces spontaneously an abundance of delicate fruits, sufficient to feed the inhabitants, who may here enjoy all things without trouble or labour.

Even the Egyptians, often regarded as a people almost entirely separate from the other western powers, believed that Isis and Orisis, representing justice and immortality, reigned from their mysterious realm in the West.

The idea of the gods living in the West proved so strong that the early Church had a difficult time explaining how Jesus came out of the East. As a way to convince pagans to convert to Christianity, the Church described Christ as the “perfect offering” from “east to west,” thus arguing that Christ had sovereignty everywhere, preferring neither east nor west.

Whatever successes the Church had in explaining this, the mystery of the West motivated everyone from Columbus to Coronado to J.R.R. Tolkien.

No one, however, prior to the sixteenth century thought of the West as synonymous with Europe. The ancient Latins had employed the term, “Europa,” but it was an idea of freedom, not an actual place. The term Europe did not come into vogue until the very early 16th century as a way to distinguish Christian Europe from the Americas to the West and the Muslims to the south and east. Since roughly 893 AD, most educated Europeans referred to their world simply as “Christendom” or the Christiana res publica. Alfred the Great, as far as is known, was the first to use the term, and he employed it as those people who resisted the Vikings. Most Christians, however, simply referred to what is now Europe as some variant of middangeard or Middle-earth. Even western Christians did not think of the Orthodox Churches as being “Eastern” until the Crusades.

One of the greatest historians of the last century, Christopher Dawson, thought of the West as a tradition, one that blended, almost seamlessly, the classical world with Christianity. He is worth quoting at length on this:

This tradition is entirely different from the influence of the pagan culture, which continued to exist in a submerged subconscious form; for it affected those elements in Christian society which were most consciously and completely Christian, like monasteries and the episcopal schools. Consequently, it is impossible to study Christian culture without studying classical culture also. St. Augustine takes us back to Cicero and Plato and Plotinus. St. Thomas takes us back to Aristotle. Dante takes us back to Statius and Virgil, and so on, throughout the course of Western Christian culture. And the same is true of Eastern Christendom in its Byzantine form, though this only reaches Russia . . . second hand and infrequently. But the same is true of theology, at least its more advanced study. The whole of the old theological literature of Catholic Christendom, both East and West, is so impregnated by classical influences that we cannot read the Greek and Latin Fathers, or even the Scholastic and 17th-century theologians without some knowledge of classical literature and philosophy.

Critically, for Dawson, literature, philosophy, and theology defined that tradition, ignoring the role of politics and political boundaries or seeing them, at best, as of secondary importance.

If there is such thing as a tradition of the West—say, from Marathon to Waterloo—then, we should probably accept the Battle of Thermopylae (480 BC) as its origin. Coming at the very end of the Persian Wars, the Spartan war king Leonidas and his 300 men held off nearly 100,000 battle hardened Persians for days. As Herodotus described it, scathingly:

But Xerxes [the Persian god king] was not persuaded any the more. Four whole days he suffered to go by, expecting that the Greeks would run away. When, however, he found on the fifth that they were not gone, thinking that their firm stand was mere impudence and recklessness, he grew wroth, and sent against them the Medes and Cissians, with orders to take them alive and bring them into this presence. Then the Medes rushed forward and charged the Greeks, but fell in vast numbers: others now took the places of the slain, and would not be beaten off, though they suffered terrible losses. In this way it became clear to all, and especially to the king, that though he had plenty of combatants, he had but very few men.

Betrayed by a fellow Greek, Leonidas and his 300 were slaughtered, but their legacy remains, and deeply so. If this was the beginning of the West, the West was born in sacrifice, justice, and resistance. When the Persian tyrant demanded that Leonidas and his men to lay down their arms and surrender, the Spartan king supposed replied: “Molon labe.” That is, come and take them. Liberty, as the ancients understood it, did not mean what it may mean to some today—that every person may do what he or she likes unless it physically harms another person. Rather, freedom meant liberty from the control of a “god-king,” as was common in the East.

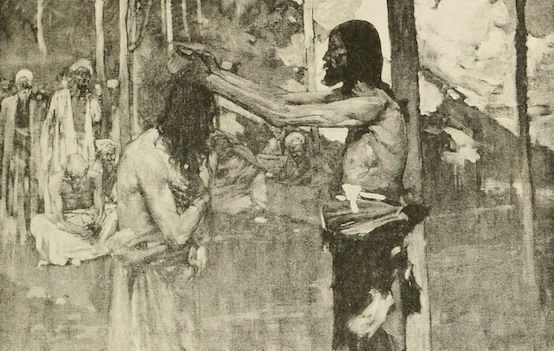

Such sacrifices have not been uncommon in the West. Even leaving the death of Jesus Christ aside for the sake of argument—after all, who can compare—we have the examples of Socrates being executed in his defense of Truth; Marc Antony’s men murdering the greatest of Roman Republicans, Marcus T. Cicero; the uncounted numbers of martyrs who died in the arenas; the Jesuits in North America, and so on.

Yet, if Leonidas unleashed what we might call western patriotism in 480—that is, something to fight against—the West must also have something to fight for.

The West did not, of course, invent sacrifice, no matter how well citizens of the West have embraced it for the past two and one-half millennia. It did, however, invent something unique in the world, something to fight for.

Sometime around the year 510 BC, a full thirty years before the death of Leonidas, a number of Greek thinkers in what is now the extreme western coast of Turkey wanted to know what the origin of all things might be. Could it be air, water, land, or sea? And, they wanted to know why all of life seems cyclical: life, middle-age, and death; and spring, summer, fall, and winter. Yet, the world did not end at the end of each cycle, it began anew. This proved universally true.

It must be noted that every civilization—east to west—has a form of ethics, a way to treat those in the in-group. It was uniquely in the West, though, that philosophy—the love of wisdom and the search for universal principles—arose. Ethics tells me how to treat my neighbor, but only philosophy allows me to understand that the person beyond my neighbor is still a fellow human. After all, each person is a universal truth wrapped in a particular manifestation.

Of those primary elements that might be the source of all being, as the first Greek philosophers argued, the one that won out over time was the one Heraclitus named, Logos—meaning inspiration, word, fire, thought, imagination. It is no wonder that the most Greek of the four Christian Gospels, that of St. John the Beloved, declares Jesus Christ as the Logos or that St. Paul believed Jesus the source of all being, reconciling all things through the Cross.

In other words, far from being racist and sexist, western civilization was the first to argue for the universal concept of the dignity of the human person, regardless of his or her accidents of birth. Those, today, who attack western civilization have absolutely no idea that their very freedom comes from those “dead white males” they so hate.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.