The Big-Box Mirage

Since Amazon has changed the way many Americans buy things, most of the big-box retailers have struggled. Fox Business recently reported that Walmart and its ilk are battling mightily to “fend off retail apocalypse.” But before the zombies come, the superstore giants want you to gas up and bravely drive over to your local strip center—at least once more, dear consumers—as legacy retailers try to create a new paradise in their old parking lots. Walmart executives announced late last year that they were “reimagining” the typical dull parking lots by building “town centers” that could “provide community space,” and “areas for the community to dwell.” And at least one new Walmart “experience” is now open for business in Temple, Texas.

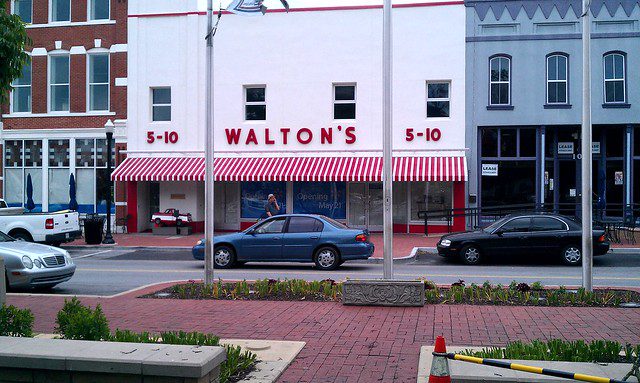

The irony is thick, and not only built up under the numerous layers of asphalt that have paved tens of thousands of acres of formerly verdant pastures; the superstores killed off remaining family hardware stores and groceries on nearby Main Streets. Over the past few decades, Walmart’s easy, free parking and low prices kept many consumers buying there—at least until the e-commerce revolution of Amazon and its imitators challenged the old superstore model of cheap, easy suburban growth.

Now Walmart is trying desperately to think outside its big boxes, yet these attempts at “reimagining” can only lead to more decline for the old paradigm of giant retail. The stagnant model of suburban real-estate development may also be a harbinger of long-term American economic decline—unless government officials and policymakers reorient incentives and make smarter infrastructure choices. It isn’t Walmart alone that is struggling to adapt the old model, but Walmart’s prominent experiment at revitalizing its big boxes is worth following closely.

* * *

Today, as the superstores gesture toward creating more human-scaled places, Walmart appears to be finally catching on to New Urbanism, the movement that has promoted the return of traditional neighborhood planning for over a quarter century. Will Walmart, with all its resources and capital, be able to recreate all the benefits of a mixed-use Main Street in an old parking lot?

The renderings provided by architects suggest that existing Walmart parking lots might be rebuilt into retail and restaurant space alongside what in more urban settings are sometimes called “pocket parks,” small patches of grass and foliage that provide some relief from the asphalt. And there may be even more. Dog parks, food trucks, and European-style food halls all abound. (One proposal in the prosperous Kansas City suburb of Lee’s Summit, Missouri even imagines a grand piano atop an outdoor stage, as if a performer will belt out some show tunes or an operetta. So it’s not exactly Nordstrom, but they’re trying.)

Other aspects of the parking lot retail strategy look remarkably akin to typical chain restaurants, albeit wanting to look more like Brooklyn bistros, with exposed brick and vintage bulbs galore. Of course, there are still plenty of stalls for private vehicles, without anyone having to parallel park or feed a meter any time soon.

Another central component of Walmart’s new strategy is the use of pop-up shops inside large modular shipping containers, that oddly appropriate symbol of global capitalism. And the most ambitious “reimagined” town centers feature large shimmering ponds, presumably to capture all the water runoff over the hard landscape, oily car stains included.

Still, for all of Walmart’s creative attempts at “reimagining,” which try to humanize suburban parking lots, they start to look a lot like typical shopping malls. Acres of parking remain, and huge arterial roads act as moats that prevent pedestrians from easily traveling beyond Walmart’s property.

To draw on urbanist James Howard Kunstler’s approach, including these sorts of similarly flawed attempts at humanizing suburban blight, Walmart’s new town centers are akin to “bandaids.” The big boxes may stem the bleeding for awhile, but death is coming eventually. It’s not just a matter of aesthetic snobbery or the rise of Amazon and online retailing. The big-box store is an outdated economic paradigm. But it’s also a way of living that is becoming unaffordable—ecologically, and also for the bottom dollar. As former President Bill Clinton’s onetime campaign slogan explains, it all comes back to “the economy, stupid.”

* * *

For decades, big-box stores were made possible by pouring billions into new suburban infrastructure, all of it subsidized by taxpayers. The good times of the 1980s and 1990s fueled the building of thousands more big-box stores, including the now-ubiquitous local Walmart. In the short term, jobs were created, and everyone was getting cheaper TVs and any number of other goods.

Of course there was never a free lunch, even at the stunningly cheap cafeterias of Ikea, those ultimate big boxes that outdo Walmart’s typical square footage with five football fields of space. Historians and economists may soon look back at these hubristic years, just prior to and after the new millennium, as the peak of the big-box sprawl experiment.

One landmark moment should not be forgotten from the annals of 1992, when President George H.W. Bush traveled on Air Force One to Arkansas to pay homage to ailing Walmart founder Sam Walton (and present him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom). Increased trade liberalization had begun during the elder-Bush years, and then in 1993, Clinton signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), for which Walmart had intensely lobbied, hoping to open thousands of stores south of the border.

After NAFTA, the decline of domestic manufacturing only accelerated. At the same time, desperate local municipalities seeking big-box employers gladly provided “tax incentives.” These big breaks, of course ultimately funded by taxpayers, created new roads—including traffic signals, power, water, and policing. Decades later, the deferred maintenance is coming due, and who will foot the bill for all the infrastructure spent to prop up the big-box experiment?

In America’s wealthier metropolitan zip codes, Walmart can “reimagine” a new place, seeking consumers to sip five-dollar lattes and buy artisanal burgers. But in many less prosperous burghs, stagnant wages won’t support such reinventions or fuel economic growth. Hundreds of Walmarts first creatively destroyed local businesses, but the company later shuttered some of its under-performing superstores themselves—sometimes only a decade or two after they were built—leaving many towns that were already struggling even poorer.

The Guardian reported in 2017 on one closed Walmart, among the deep poverty of rural West Virginia: “Walmart descended in 2005 on the site of an old Kmart, like the spacecraft of alien botanists that lands in the forest at the start of the movie ET. And there it sat: a massive gash of concrete encircled by nature’s abundance.” Over 100,000 square feet once employed over 300 people, serving as a kind of town square; only a decade later, it was empty.

Some people might be surprised that the store gave up on the area so quickly. An average big-box store is only designed for a 15-to-20-year lifespan, Joe Minicozzi, an urbanist consultant, has explained that a Walmart executive once disclosed. So if a distant corporation decides to cut their losses and move out, the local officials are stuck with maintaining the extra public infrastructure for years to come, as well as a further reduced tax base.

This is why New Urbanists and others care about more than creating beautiful, traditional downtowns. It’s good fiscal sense, too. Doubling down on more big-box fads can’t support sustainable places. Minicozzi found one example from Asheville, North Carolina, where analyzing the tax structure with a traditional street “realizes an astounding +800 percent greater return” on downtown tax revenue—as compared to “when ground is broken near the city limits for a large single-use development like a Super Walmart.” In short, the city of Asheville “yields $360,000 more in tax revenue to city government than an acre of strip malls or big box stores.”

The currently “reimagined” Walmart won’t fundamentally change the economics, even if it tries to change the paradigm. There are no plans to include density near homes or offices; Walmart even generously suggests that the new big boxes can provide better bike and walking paths to reach other destinations—yet just try to safely cross a multi-lane arterial road on a bike or scooter.

There is no shortage of new research on how to fix badly designed big boxes, including the wealth of case studies in Retrofitting Suburbia by Ellen Dunham-Jones and June Williamson. Walmart is apparently uninterested in these retrofits, which break up asphalt deserts of superblocks into a traditional street grid, slowing down cars. (In Englewood, Colorado, city officials successfully pushed Walmart for a better facade and tree-lined streetscape, but this is the exception rather than the rule.) Many retrofits hide large parking lots from the street, and at least two-story buildings create space for residential housing. Mixed-use developments also make economic sense, allowing developers “to better ride out real estate market cycles by having a mixed portfolio, and being able to more flexibly respond to shifts in demand.”

In some cases, where there is currently no demand for redevelopment, Dunham-Jones and Williamson suggest “regreening” large parcels of land for small-scale agriculture or conservation. This solution may make the most sense for underperforming big boxes, particularly at the edges of both large and small cities. In so many places, then as now, municipalities are tempted to allow development on greenfield sites, even following New Urbanist principles. But it would be unwise to ignore languishing core downtowns when in many cases regional population growth is only modest, as in the Rust Belt, for example.

* * *

The stakes may be higher for the future of Walmart than any of the other big boxes, notably the large real-estate footprint it has created over the past few decades. Local municipalities and state officials should not allow big-box stores to duck responsibility for the mess they helped create; now Walmart and others are using court decisions known as “dark stores” to depreciate their properties, letting them become worthless, and leaving invested cities and counties stuck with the tab. It’s not only an impending economic disaster, but there is also a moral imperative to insist on solidarity between capital and local taxpayers.

In recent years, Walmart has put moral pressure on localities to pay workers higher wages. Cities and towns must wake up to another moral imperative—that of economically and ecologically responsible land use. It’s not simply a New Urbanist fashion, but a way forward for retrofitting our communities as resilient places that will not squander past investment, and continue to make the same mistakes.

Almost all suburban and exurban real-estate developers and local officials are heavily invested in the old formula of enabling sprawl to create wealth, and changing that paradigm will be difficult. Yet waking up to the big-box mirage will build American prosperity on a firmer foundation, one block at a time.

Lewis McCrary is executive editor of The American Conservative. This New Urbanism series is supported by the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.