‘Top Gun: Maverick’ — Not Feelin’ It

Just got back from seeing the new Top Gun movie. I must be one of the last Americans in the world to have seen this movie, which has been out for a while, and is a big hit. It was about what I expected: a movie about Tom Cruise, men, and technology. Despite some truly fantastic flight and air combat scenes, the movie landed with a thud, at least with me. On the walk back home, I tried to figure out why.

The first Top Gun film came out in 1986, when the US was in full flush of the Reagan-era patriotic revival. We were still in the Cold War, but Gorbachev had arrived on the scene, and it looked like we might win. It is hard to overstate the sense of confidence that America had then -- a confidence that was most vividly expressed through hallowing the military. This had a lot to do with exorcising the demons of our Vietnam failure, and the Iran debacle. Tom Cruise was 24 years old in 1986; he was the face of America's brash new sense of itself.

Tom Cruise is 60 today. True, he looks damn good for 60, but he is still puffy and soft around the edges, and doesn't have the swagger he used to have. And you know, he looks like America today, too. This, I think, accounts for why the new Top Gun is so tinny. It's harder to relate to, given the wars and other events of the past twenty years. Maybe it's just me, but sitting in the movie theater tonight watching the film, I enjoyed it on a surface level, but I'm no longer the audience for this shiny, shallow war movie.

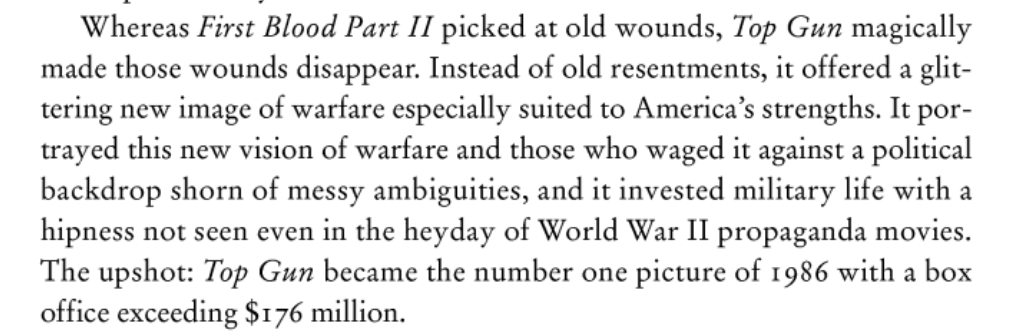

The lessons of Andrew Bacevich's 2005 book The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced By War have sunk in. Take a look at this graf from the book, talking about the effect of the first Top Gun:

"Shorn of messy ambiguities" indeed. This new movie has US Navy pilots engaged in a mission to destroy a nuclear weapons facility in an unnamed country, whose nuclear program threatens "our allies in the region." You're thinking Iran, but the battlefield is Alpine. It's a war movie manufactured to offend no one. Yet it seems like an empty exercise in nostalgia, trying to capture that old Reagan-era magic.

On the walk home, I think I was able to put my finger on why this movie rubbed me the wrong way -- and it's the Bacevich point, about how movies like this prepared the American people to favor war. Here is a transcript of the retired US Army colonel, historian, and sometimes TAC contributor, talking about his book the year it came out:

In my new book I argue that, just like the domestic policy component, the foreign policy components of the cocktail were there before 9/11 occurred, particularly the infatuation with military power and the belief in the American mission. There is of course nothing new about the latter. A sense of mission goes all the way back to the American colonies. John Winthrop's "city on the hill" sermon has been cited over and over by American leaders, to suggest that we're a providentially special nation. Throughout American history, there have been two dominant ideas about how to implement this mission. One way is to serve as an exemplar of a God-fearing community, to use the language of the founders—or, to use the language of Woodrow Wilson and Ronald Reagan, of a democracy. The other camp believes that America should assert its presence in the world by aggressively pursuing its mission—made most explicit in Woodrow Wilson's famous line about making the world "safe for democracy."

What is new today is the other component of the cocktail, a confidence that the American mastery of warfare now puts us in a position as never before, to aggressively pursue our mission in the world. After 9/11, President Bush clearly articulated that proposition in vowing to make an end to evil. He could not have persuaded the American public about the plausibility of that idea if we weren't already predisposed to believe that military power had become our nation's strong suit.

More, on what Bacevich called "the new aesthetic of war":

... The film Top Gun was the number one hit the year it came out (1986). In contrast to movies about Vietnam, which depicted the mindless, filthy, and exhausting side of war, Top Gun gave us a picture of good-looking pilots in starched white uniforms. This marked a radical departure from the traditional focus on the perils of military combat that until then had tended to shape the American understanding of war. According to Top Gun, war can be clean, high tech, and glamorous—an image reinforced in Tom Clancy's books.

American popular culture helped to create a set of expectations about what war was becoming, so that by the time the Cold War ended, a new aesthetic of war had emerged, making the prospect of engaging in military conflict palatable to the average American. You may recall the reporting on the Kosovo War—it was all about the pilots, the glamorous side of it. It almost made war seem an antiseptic kind of enterprise, which was very misleading. Indeed, as we've seen in Iraq, war is a messy and ugly business.

He's right about that. I remember it. Look, it's not Tom Cruise's fault that George W. Bush launched the disastrous Iraq War, but movies like these played a key role in propagandizing us to believe that war is something other than it is. After the extremely costly military failures of the past twenty years, I'm not interested in buying what that commercial is selling. Not this time. Clearly I'm in a minority here, as Top Gun: Maverick has just become one of the top ten highest grossing movies in US history.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

UPDATE: Relatedly, here's a Joshua Treviño post from back in January, ruminating on the appeal of techno-thrillers to himself as a younger man. He writes that the Tom Clancy books he loved in the 1980s, and the vision of military life they portrayed, did not survive his actual experience in the Army in the 1990s. This excerpt is key:

Red Storm Rising is, as mentioned, a product of its time, and so quite a lot of it does not feel nearly so relevant or timeless as these two scenarios within it. American-military hyper-competence, marked with candor and professionalism, was an easy sell in the 1980s — especially in reaction to the post-Vietnam reforms that essentially rescued the force from itself — but it is much less so in the era of General Mark Milley (take your pick: “white rage,” suppressing the Iraq War historical report, the ACFT disaster, on and on) and drone strikes wiping out whole families because of process blunders. For those of us of a certain age, there was a historical moment when the Armed Forces of the United States really were this good, and this honest: perhaps a twenty-year window, from Grenada 1983 to Iraq 2003. But in 2022 there is much to prove, and the outcome feels uncertain. The stuff of the American soldier, airman, sailor, Marine, coastguardsman, Guardian, Guardsman, et al., seems as strong as it ever was. Their leadership above a certain level — usually the level at which the United States Senate starts actively involving itself in assignments and promotions — inspires less confidence. That isn’t to say we aren’t what we were. It is to say we have forfeited the benefit of the doubt.