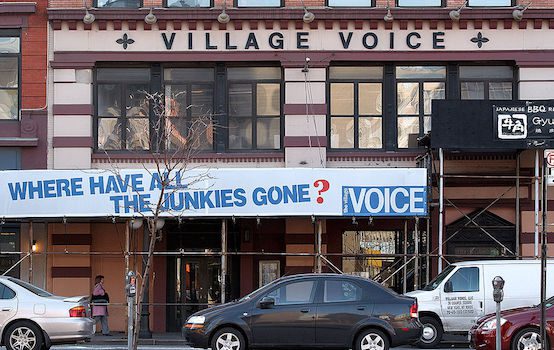

The Village Voice Goes Silent, Finally

How do you write an obituary for someone who was a great and loving role model to the parents you love, but who was abusive and dismissive to you and your friends?

When I first heard about the death of the Village Voice on August 31 (its print edition was euthanized last year, which had left it publishing mostly online), I had much the same reaction as I had to the December 2017 downsizing and restructuring at the Voice’s longtime Los Angeles counterpart LA Weekly. I churlishly thought that I would have just as much sympathy for them as they had for many of my friends and colleagues who weren’t among the few chosen to work in their hallowed halls—which is to say, almost none. When Entertainment Today, LA Valley Beat/City Beat, the Brooklyn Rail, and other “alt-weeklies” died gruesome deaths in the run-up or aftermath of the Great Recession (I worked for ET early in my career), the reaction of the league-leading LA Weekly and Village Voice people at the time ranged from eye-rolling laughter to dancing on our graves.

More to the point, thanks to corporatization and consolidation, no Millennial and very few younger Xers can really remember when these papers were truly “anti-establishment” or even at the top of their game in any real sense. By then, the status consciousness, tone policing, snobbery, and credentialism of the Voice and the Weekly (and their very corporate parents’ corporate culture) ensured that there was more of a revolving door than a boundary line between them and the usual suspects over at the “mainstream” Los Angeles and New York Times.

Yet when I talk to Boomer writers and artists, whether they swore by or swore at what appeared in the Voice, almost all recognized it as the very symbol of New York’s vitality, a carnival of cultures and classes, decades before “diversity” became a political password. Maybe, as this eulogy suggests, the city that the the alt-weekly gave “voice” to is no longer there.

When the Village Voice started in the Eisenhower 1950s, TV news had barely come into its own. Most network newscasts were 15 minutes long, and local TV news was ticky-tacky. Newspapers and national magazines were strictly establishment, adhering to Great Consensus standards of “objectivity” and news that was “fit to print.” There was no room for far-left thought and certainly no truck with conservatives (which is how National Review finally came to be in 1955, coincidentally the same year as the Voice). Even when LA Weekly started in the disco-soundtracked malaise of 1978, the “news” accessible to most media-savvy Angelenos were the Los Angeles Times and other established papers, and the network owned and operated TV stations.

What the Village Voice did for New York journalism was to cover the city and its people toiling and entertaining and organizing in the shadows. Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather were definitely not hanging out with Patti Smith and David Byrne at CBGB. Vincent Canby or Howard Rosenberg might review an Abel Ferrara or a John Waters grindcore film, or a La MaMa off-Broadway play, but an in-depth feature with the auteurs themselves? The Times wasn’t doing profiles of young black community organizers or socialist housing league presidents (let alone respectful ones). John Chancellor and David Brinkley weren’t known for in-depth coverage of Stonewall or Harvey Milk-era Gay Liberation parades. Ghetto and barrio culture only became newsworthy when racial tensions festered and exploded into the mainstream consciousness, or someone wound up dead at the hands of the police, like Eleanor Bumpurs in 1984.

As a respected and accomplished Boomer-era composer recently told me, when he was making it as a young musician in the Big Apple in the early 1970s, he and his set thought of the Voice as “the New York Times for nonconformists.” It provided a truly alternative “voice” to the processed cheese pabulum and establishment headlines of the mainstream media. In its heyday, the Voice was a place where indisputably talented and iconoclastic writers who were too “out there” to get hired at the mainstream spots could not only pick up a paycheck and a byline credit but also have the chance to rub shoulders with Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal. Where writers who redefined arts criticism like Robert Christgau, Nat Hentoff, Andrew Sarris, and James Wolcott got some of their first and best breaks. Where conservatives and suburban liberals alike could shake their fists at Alexander Cockburn’s near-open communism, or the latest Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit.

The Voice employed to their very last day both new and old greats who did nothing but good by the standards of journalism and their communities. But it also housed writers and editors who were smug caricatures of everything they supposedly despised. Towards the end of the paper’s 63-year lifespan, it became an insular clique rather than a sanctuary for brilliant misfits and rebels. This was a storied institution that had earned respect but slowly lost it, thanks in part to the corporate buyouts and the inevitable dimming of its once strong independent compass.

As former (and understandably disgruntled) contributor Harry Siegel noted, the grim fate of the Voice symbolizes an era where journalism is moving more and more away from a self-sustaining business model towards becoming a bauble or plaything of rich social climbers who want to buy their way into influence with a media footprint platform. (The uber-controversial restructuring at LA Weekly did the same thing.)

Let’s have a little audit, shall we? The Washington Post would have died in darkness if it weren’t for Jeff Bezos. Variety would have stopped the presses without (racing/auto dealer legend Roger’s son) Jay Penske. The brilliant scientist and Big Pharma bigwig Patrick Soon-Shiong gave the Los Angeles Times the vitamin injection that saved it from slipping into a coma. (During the worst of the Great Recession, the Times was petitioning in grocery stores to keep its print circulation at acceptable levels, and the main selling point wasn’t groundbreaking journalism but “!Mas Cupones!” Around the same time, the New York Times had to take out a loan against its Times Square headquarters.)

When venues exist from every ideological flavor from Jacobin to Breitbart, where is the “brand” for a Village Voice or an LA Weekly? When white nationalist websites like the Daily Stormer and “tankie” Twitter Marxists making campy memes and normalizing their prejudices are only a Google or Yahoo click away, how “edgy” and “transgressive” can a decades-old alt-weekly really remain? When NowThis and Attn.com are offering easily shareable, addictively watchable video news content parceled out in stylishly edited three-to-five minute chunks, how many hip Millennials are going to read through an inky, folded newsprint magazine the size of an Olympic pool drain?

Yet we cannot fail to recognize the storied past that preceded the faded present. The demise of these alt-weeklies, and the death of the era they epitomized, is almost the journalistic equivalent of having to move Mom into the nursing home or take the keys to his 15-year-old Caddie or Lexus away from dear old Dad. Giants once walked in those hollowed-out shells, and for their sakes, we can only offer a requiem worthy of the heavyweights they once were.

So long, Village Voice. It wasn’t always nice to know you, but I’ll try to remember you fondly now that you’re gone.

Telly Davidson is the author of a new book, Culture War: How the 90’s Made Us Who We Are Today (Like it Or Not). He has written on culture for ATTN, FrumForum, All About Jazz, FilmStew, and Guitar Player, and worked on the Emmy-nominated PBS series “Pioneers of Television.”