William Gaddis Today

William Gaddis has not been neglected, but he has not been fully understood either. His work doesn’t critique consumerism as much as it does self-referential originality—a world “that has given up on transcendent values.” Chris Beha explains in Harper’s:

Readers have often understood The Recognitions’ obsession with counterfeiting as a familiar Fifties critique of American phoniness. ‘Peel away the erudition,’ Jonathan Franzen wrote about the novel, ‘and you have The Catcher in the Rye.’” But Gaddis makes clear throughout that he is after bigger, more interesting game; his real target is not fakery but something like its opposite, what a teacher of Wyatt’s calls ‘that romantic disease, originality’: ‘Even two hundred years ago who wanted to be original, to be original was to admit that you could not do a thing the right way, so you could only do it your own way. When you paint you do not try to be original, only you think about your work, how to make it better, so you copy masters, only masters, for with each copy of a copy the form degenerates.’

This notion of degeneration owes something to Plato, for whom the visible world is a copy of the eternal forms and mimetic art a copy of that copy. In this view, the artist’s true job is not to depict our transient reality but to pierce through it and give us some access to the absolute. This is what contemporary viewers miss, Wyatt insists, when they focus on the meticulous craftsmanship of the Old Masters. ‘This . . . these . . . the art historians and the critics talking about every object and . . . everything having its own form and density and . . . its own character in Flemish paintings, but is that all there is to it? Do you know why everything does? Because they found God everywhere. There was nothing God did not watch over, nothing, and so this . . . and so in the painting every detail reflects . . . God’s concern with the most insignificant objects in life, with everything, because God did not relax for an instant then, and neither could the painter then.’

By these lights, the problem with forgery is not a lack of originality but the fact that it divorces technique from its proper aim, leading to empty virtuosity. Which, the novel suggests, is also the more general problem with the modern world—meaning not the air-conditioned nightmare of midcentury America, but the West from give or take the Reformation on: ‘Reason supplied means, and eliminated ends. What followed was entirely reasonable: the means, so abruptly brought within reach, became ends in themselves.’

In other news: The Brooklyn Museum sells off part of its permanent collection for $6.6 million. The Baltimore Museum of Art is planning on doing the same, but former board members are pushing back: “Signed and dispatched yesterday by former trustees and advisory committee members of the BMA, as well as by various local artworld luminaries, the letter calls upon Maryland’s Attorney General and its Secretary of State to investigate the museum as a consequence of its dicey decision to ‘deaccession three iconic works from its collection’.”

The return of Confucianism in China: “In just a few years, Confucianism has acquired a new face, with two sides. Moderates such as Chen Ming and the distinguished Tu Weiming regard the tradition as potentially providing a kind of civil religion for China, a source of moral authority and perhaps political legitimacy for rulers who accept its general regula and moral precepts. This view is largely consistent with classical Confucianism. More radical is the proposal of Jiang Qing. He and his followers wish to see a Confucian state religion institutionalized as an alternative to Western liberal democratic ideals, to which they are hostile. Jiang’s cultural nationalism imagines public rules and rituals. For instance, participants in the Nishan Forum were given ‘Neo-Confucian’ vestments to wear in the general ceremonies and at academic sessions. Drawing on part of the 1982 Constitution, Jiang’s Neo-Confucianism emphasizes Chinese ethnicity, language, culture, and history. As Lei Sun, professor of Confucian philosophy at Tongji University, puts it, ‘Political legitimacy in China has shifted from a basis in revolution to a basis in Chinese history and culture.’ This in itself might seem a welcome development. But for some Neo-Confucians, it is not nearly enough.”

Colin Grant reviews Claude McKay’s Romance in Marseille, which failed to find a publisher in McKay’s lifetime and has “languished in archives at Yale University and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture” until Penguin published it earlier this year: “Romance in Marseille is a pitiful tale, but McKay said his intention was not to write ‘a sentimental story.’ He succeeded.”

Victorian London’s last illustrator: “Aubrey Beardsley, who died in 1898 at the age of 25, was a friend of Oscar Wilde and a protégé of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones. He looked like a waif and dressed like a dandy. He died of tuberculosis, the same disease that claimed Shelley, two-thirds of the Brontës, and Mimì from La Bohème. The whole, dizzying opera of 19th-century aestheticism seems to reach its finale in him. So why, then, do Beardsley’s drawings—the subject of a magnificent exhibition opening at the Musée d’Orsay next week—feel so contemporary?”

The avant-garde’s cleverest rogue: “The avant-garde of the early 20th century had more than its fair share of clever rogues, and no one played the role with more self-conscious élan than Walter Serner, who compiled an aphoristic guide to succeeding as a con artist in a Europe roiled by social upheaval, economic chaos and political intrigue after the First World War.”

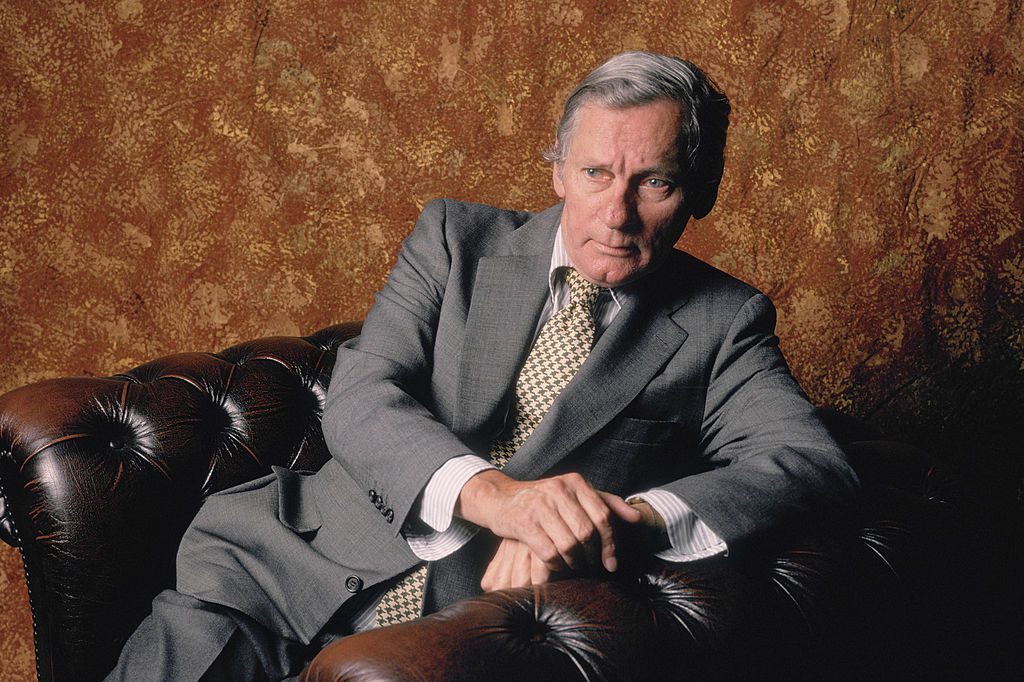

Photo: Werfen