The Tragedy of Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound was a fascist and an unrepentant anti-Semite, but he is also a tragic figure, William Wall writes in The Dublin Review of Books—a great poet whose mind was poisoned by hatred:

Ezra Pound is, perhaps, the most troubling of all the Modernist presences in Anglophone literature – a fascist and an unrepentant antisemite even after the Holocaust revealed the ultimate end of that obnoxious prejudice – yet he was a brilliant poet, a brilliant synthesiser of cultures and absolutely central to Modernism in English. Born in Hailey, Idaho in 1885, he came to Europe in 1908, first to Gibraltar as a tour guide, later to Genoa and then to London, where he lived for ten years. During his stay there he made the acquaintance of all the Modernist poets and was, by the time he left for Paris and Italy, already a significant figure in that literary movement. He arrived in Rapallo, Italy, in 1924 and lived there until 1945, when he was forcibly repatriated to the USA to stand trial for his wartime collaboration with the Italian government. While in London he was a hugely influential editor and critic and his influence would be continued from his base in Italy. His role in the work of Eliot and Yeats, among many others, is well-known, as is his furious proselytising on behalf of James Joyce, who said of him: ‘It is probable that but for him I should still be the unknown drudge that he discovered.’ Eliot, in dedicating ‘The Waste Land’ to Pound, called him il miglior fabbro ‑ the best craftsman (a quotation from Dante).

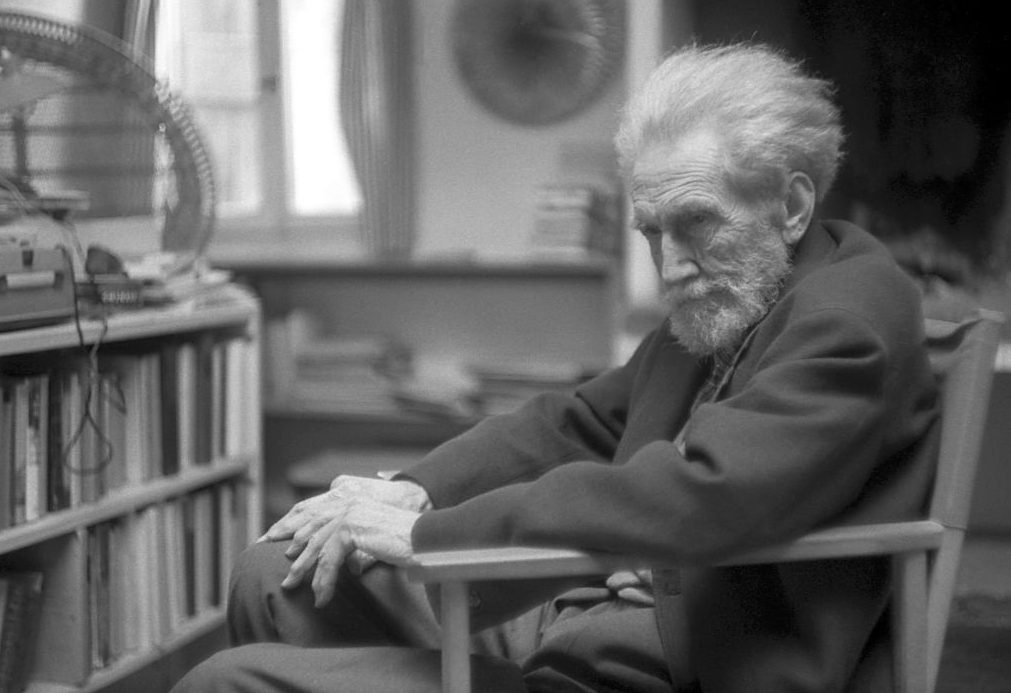

Ezra Pound, Italy and the Cantos comes from the pen of one of the foremost Pound critics. Massimo Bacigalupo grew up in Rapallo, Pound’s long-term home. His parents were friends of Pound’s and Bacigalupo himself would come to know him in what he calls his ‘complex and tormented final phase’ in the postwar period when, as a broken man, he returned to his old ground. Besides literary criticism, Bacigalupo is an accomplished and multi-award-winning short-film-maker (the Turin Film festival dedicated a retrospective to his work in 2010) and many of the photographs included in the text are his; a prize-winning translator of, among others, Pound, Yeats and Wordsworth; and emeritus professor of Anglo-American literature at the University of Genoa. Bacigalupo’s personal relationship with the Pounds informs every aspect of his book and lends a more intimate air to his acute observations.

Had Pound, like Eliot, who was equally antisemitic and had fascist tendencies, confined himself to poetry we might remember him differently but it was his misfortune to fall under the spell of fascism and to be incapable of circumspection. Yeats, who admired the Blueshirts in Ireland, shared Pound’s contempt for democracy – indeed for the demos – his belief in an ‘aristocracy of the arts’ and his contempt for the bourgeoisie. In the chaos that followed the First World War the idea of a political strongman was fatally attractive to many intellectuals. This is the context of Pound’s fascism, though I believe that antisemitism was the real poison in his blood. He correctly argued that ‘usury’, which we would call ‘finance capitalism’, would come to dominate Western society but believed it was a Jewish conspiracy and fascism was the cure. Not only does he argue that Jews are usurers but also very often the converse that financiers must be Jews, as in the case of the Scot John Law, who was controller general for France during the reign of Louis XIV. Pound calls him ‘Lawvi or Levi’, in other words, he guessed wrongly that Law was a cover for the Jewish name Levi – a classic antisemitic inductive error. He has the conspiracy theorist’s eye for detail, as well as his failure to grasp reality.

Pound’s biggest mistake was to make regular broadcasts for the fascist government of Italy during the war. These broadcasts, though never as targeted towards the Axis war effort as those of William Joyce, known as Lord Haw Haw, who was eventually hanged by the British, were nevertheless rightly considered rank propaganda for an enemy power. Pound’s broadcasts mainly consisted of rambling attacks on ‘usury’, Jews and the United States as well as samples of his own poetry, but they were monitored in the USA and considered to be aimed at undermining morale. In 1943, he was indicted for treason in absentia. On capture he was detained in a ‘cage’ in Pisa for some time and then repatriated to stand trial. Because of the influence of his friends he did not receive the death sentence but was committed to St Elizabeth’s Psychiatric Hospital near Washington, where he remained for thirteen years.

Bacigalupo does not shy away from what he calls ‘the Pound vortex’, which, he says, ‘must be acknowledged in all its bewildering violence and historical dimensions’. Strangely, it is the Italian writers of the postwar Left who were most forgiving of his wartime stance. Pier Paolo Pasolini, for example, perhaps the most ferocious of antifascist writers and auteurs, was an admirer and there is a brief account here of a gentle and supportive interview he conducted with the poet in his final years. Carlo Izzo was another – scholar and translator extraordinaire of among many others Liam O’Flaherty – Pound referred to him as ‘my best translator’. Remarkably, considering that Izzo was a communist and a committed antifascist who married a Jewish woman and whose position at the University of Bologna was cancelled under Mussolini’s Race Law, the two men continued to correspond throughout the war years. In 1958, Izzo wrote sadly of Pound: ‘That he could have identified his world-view with that horror of doctrines that are among the most inhuman of all time, does suggest mental aberration. To say to an Italian Jew, on the day that Italy passed the racial laws that are so alien to the spirit of our civilisation: ‘I am sorry, but it is well done,’ is the act of someone not in his right mind. Six million of those ‘I am sorry’ wouldn’t have saved one of the six million innocents who were “Liquidated.” I remember this incident without rancour …’

Ignore that throwaway line about Eliot, and read the rest.

In other news: Steven F. Hayward reviews the final volume of Rick Perlstein’s chronicle of modern American conservatism: “The first thing a reader will learn from the final installment of Rick Perlstein’s epic four-volume narrative on the rise of the right from 1964 to 1980 is that Simon & Schuster, one of the world’s premier trade imprints, apparently no longer employs copy editors, fact-checkers, or proofreaders. Reaganland, coming in at more than 1,000 pages, is riddled with so many typos, misspellings, factual errors, repetitions, and overindulgences of the author’s sarcasm that it distracts from the worthy content of the narrative, which is uneven in any case. North Carolina’s Senator Sam Ervin is transmuted into Sam Erving. The book says the GOP hadn’t controlled the House of Representatives since the Hoover administration when it did so in 1947–48 and 1953–54. It says that New York had 21 electoral votes in 1976 when it had 41. It misidentifies ABC News anchor Frank Reynolds by placing him at NBC, where he never worked. It claims that the Liberty Fund was a creation of Charles Koch; it wasn’t. It says George H.W. Bush beat Ronald Reagan in the 1980 Oregon primary 58.3 percent to 54 percent, which would be a neat trick of overvoting. Beyond these embarrassments are the gross misstatements and mischaracterizations of many particulars, from the 1965 Moynihan Report on the black family to the landmark Buckley v. Valeo Supreme Court decision in 1976. This is merely a sample of what could be a very long list.”

The more things change, the more they stay the same: “The best thing about reading lively narrative histories is the realization that we do not, in fact, live in uniquely strange times. The last few years have been unsettling, to say the least; but as Matthew Lockwood reminds us in his new book To Begin the World Over Again, so were the 1770s, ’80s, and ’90s. In his lengthy, leisurely study, he takes his readers from the eye of the storm in North America and London to the myriad lands that were affected by the American War of Independence, demonstrating that “a local protest over taxes in a remote corner of North America would end on the streets of Dublin, the mountains of Peru, the beaches of Australia, and the jungles of India.” Lockwood draws a moral from this spectacle and lays it out in his introduction: ‘Examining the revolution from a truly global perspective, both geographically and thematically, forcefully reveals the often tragic interconnectedness of the world, compelling us to contemplate ourselves in an entangled world rather than as an isolated, exceptional chosen people. Removing the blinkers of a narrowly national political point of view opens new horizons of understanding, allowing us to realize the most urgent lesson taught by America’s founding moment: American actions have, and have always had, unforeseen, unimagined global consequences.’”

Revisiting France’s old regime: “In a narrow sense, France before 1789 is not about the revolution itself. Instead the book aims to provide a snapshot of how the old regime functioned. In a broader sense, however, all books about 18th-century France are (at least indirectly) about the history of the revolution — for all authors writing after 1789 know what is coming and can hardly ignore it. As Elster remarks of his own book, ‘the portrait of the [old] regime is harnessed to the end of understanding the Revolution.’ France before 1789 is the first volume in an intended trilogy. The second volume will cover America before 1776 and thereby lay the groundwork for the third, which will be a comparison of the constitution-making processes in the two countries. Accordingly, the first volume discusses the features of old-regime France that are most relevant for understanding the lead-up to the constitution of 1791.”

It “would be impossible not to find something interesting” in Peter Burke’s new book The Polymath: A Cultural History from Leonardo da Vinci to Susan Sontag, Dmitri Levitin writes, but “Burke’s story is ultimately one of decline, from the ‘monsters of erudition’ of the 17th century to the present era of specialisation”: “As for the later period, many of Burke’s polymaths are from the humanities and ranged widely in their roles as ‘critics’, ‘cultural commentators’ or ‘public intellectuals’. Does this really qualify them for the title of polymath? It is one of the realities of Western history that someone who has done well in a humanistic field, has a vague talent for prose and, more often than not, is from a privileged background and has the right connections is frequently invited to offer their opinions on subjects in which they have no discernible expertise. To pick an easy target from those mentioned by Burke, there can be no doubt that Noam Chomsky is a seminal linguist, but it is not clear that without his prior reputation his writings on politics would be taken very seriously (this point applies across the political spectrum). Indeed, it might even be claimed that the mythology of the polymathic public intellectual is inherently elitist: why should the political opinions of a philosopher, historian or novelist receive more attention than those of a nurse or teacher? Indeed, perhaps there are good reasons why they should not. Burke addresses briefly the accusations of superficiality, dilettantism and even charlatanism that have been levelled at polymaths throughout history. I would have liked to hear more about this. Burke does not mention that one of the most recent figures on his list, Gilles Deleuze, was exposed as having misused mathematical concepts as part of a process of mystification and deliberate obscurantism (every student should read Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont’s debunking of his work, Intellectual Impostures). Perhaps the real modern polymaths are the hidden ones who do not themselves grab the limelight but have the expertise to bring together different fields of knowledge: librarians, teachers, editors of literary journals…”

Rain, northern England, and W. H. Auden: “ Many months into our own extremely cautious Covid regime, it’s not the weather for an excursion, but we’ve waited all week. At a pinch the forecast is open to a faintly benign interpretation, so we set out for Alston around noon. I imagine W. H. Auden working in a cabin on Fire Island in summer with a map of Alston Moor pinned to the wall. I have the OS Landranger map, my partner is driving, and the dogs sit in the back looking pessimistic. Even though the lead-mining district is an hour’s drive from home, we rarely manage to go. ‘Get there if you can’, Auden wrote during the Depression in 1930, ‘and see the land you were once proud to own, / Though the roads have almost vanished and the expresses never run.’”

For you parents and grandparents out there, Adam Gopnik recommends Ludwig Bemelmans’s newly reissued Sunshine: A Story About the City of New York: “Where Bemelmans’s Paris is formal and ceremonial — its fun found in the space between the formality (all those grand green lawns, those perpetual perpendicular lines) and the smaller idiosyncratic acts of mischief undertaken by his children — Bemelmans’s New York, though depicted in a variant of the same Fauvist style (all slapdash black outlines and broad blocks of bright color), is properly crowded and chaotic, with the mischief arriving from the attempts to bring ceremonial order to the civic chaos, without entirely betraying the civic chaos. The story, slight enough, and told in Bemelmans’s familiarly sweet and efficient doggerel style — using, indeed, the same laconic singsong meter as the Madeline books — takes as its subject the great New York subject, perhaps the only New York subject: the search for living space, and quarrels over noise after it is found.”

Photo: Puente Nuevo de Ronda

Comments