Orwell in Cuba

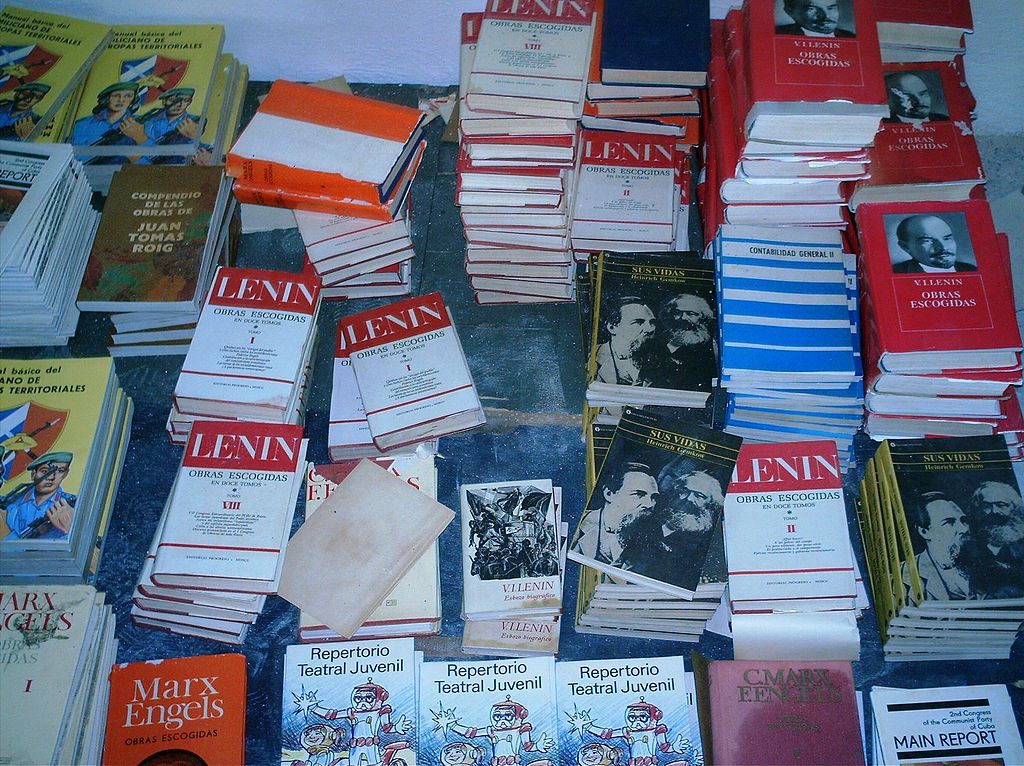

Good morning. “In 2016, a Cuban publishing house announced that it would launch a new translation of George Orwell’s 1984 at Havana’s International Book Fair. The choice was puzzling. A one-party state with a long history of censorship was doing more than allowing the publication of a classic critique of totalitarianism: it was mass-producing it and promoting it at a major event.” Amanda Perry reviews Frédérick Lavoie’s newly translated book Orwell in Cuba:

As an investigation of how censorship affects literature, the arts, and the media, Orwell in Cuba is nuanced and compelling. The central challenge in confronting Cuban censorship is its indeterminacy. The highly visible arrests of the artists El Sexto and Tania Bruguera are exceptions to a process that is generally much more covert. There is no official list of banned books, for one thing; unwanted titles simply go undistributed. Although all presses were nationalized in the ’60s, the mechanisms of editorial decision making remain obscure. Individuals push the envelope, proposing new editions of material previously assumed to be unacceptable. The only clear red line is the explicit and named denunciation of the Castro brothers. Even then, different rules apply for foreigners, and Lavoie is able to cross that line with seemingly few consequences.

In his quest to unravel the details behind 1984’s publication, Lavoie constantly runs up against these uncertainties. Some of his interlocutors may be lying. The vast majority have only a partial idea of what is going on. At times, he even comes off as paranoid — assuming acts of resistance when none were intended or being taken aback that some of his companions criticize the regime so openly. Indeed, it’s almost commonplace among literature scholars in Cuba to discuss and condemn the intense censorship of the 1970s, as many writers banned during that period have since been rehabilitated. But ongoing uncertainty about what is now allowed is also part of how censorship functions. People moderate themselves in an effort to avoid crossing poorly defined boundaries, making it only rarely necessary for the regime itself to enforce them.

Speaking of Orwell, he wouldn’t have become the writer he was without his first wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, Sylvia Topp argues in Eileen: The Making of George Orwell. Martin Tyrrell reviews: “Eileen, one of the first women to graduate from Oxford, typically set aside anything she might have wanted for herself the better to help ‘Orwell fulfil his destiny’, be that writing, adopting a child, or moving to the Inner Hebrides. Had she not taken up with Orwell, she might have found success, if not fame, in her own right, possibly as an academic or a child psychologist. Her loss was Orwell’s gain, something neither he nor the majority of his biographers have properly taken on board.”

In other news: A researcher claims he has identified the spot where Van Gogh completed his last painting.

Bob Ross died 25 years ago. He’s more popular than ever. “I was in a room on the side of a big-box craft store in the suburbs north of Dallas, about to start a class taught by John Fowler, a Bob Ross–certified instructor—which means that he spent three weeks in Florida learning the wet-on-wet painting technique Ross employed on television. A tall, bespectacled man in his 60s, with a light beard and a deep voice and soothing cadence reminiscent of Ross himself, John explained that he has a few things in common with the puffy-haired painter. They both spent many years in the Air Force, for example, and both retired with the rank of master sergeant. I’d learn he also uses some Bob Ross vernacular, sprinkling instructions with expressions like ‘We don’t make mistakes, we just have happy accidents.’ John watched Bob Ross on The Joy of Painting for years, both during the show’s original run in the 1980s and ’90s, then later by streaming it. Four years ago, John decided to get some paint and a canvas and try painting along with the host. He liked it so much that he took some lessons. Then he liked those so much he paid about $400, not including supplies or lodging, and signed up for the official ‘Certified Ross Instructor’ class, taught by Bob Ross Inc. trainers. When we met, John was wearing a black T-shirt with the painter’s face on it . . . Bob Ross Inc. is still thriving. The company owns hundreds of highly sought after Bob Ross originals. (It’s almost impossible to find one of his paintings for sale.) The official Bob Ross YouTube channel, run by the company, has over 4 million subscribers and more than 360 million total views.”

Mozart family fun: “It’s 1771, you’re in Milan, and your 14-year-old genius son has just premiered his new opera. How do you reward him? What would be a fun family excursion in an era before multiplexes or theme parks?” Go to a hanging: “‘I saw four rascals hanged here on the Piazza del Duomo,’ wrote young Wolfgang back to his sister Maria Anna (‘Nannerl’), excitedly. ‘They hang them just as they do in Lyons.’ He was already something of a connoisseur of public executions. The Mozarts had spent four weeks in Lyons in 1766, and, as the music historian Stanley Sadie points out, Leopold had clearly taken his son (10) and daughter (15) along to a hanging ‘for a jolly treat one free afternoon’. Mozart’s letters deliver many such jolts — reminders that, however directly we might feel that Mozart’s music speaks to us, he’s not a man of our time. But for every shock of difference, there’s a start of recognition.”

Daniel Blank reviews How to Think Like Shakespeare: “How to Think Like Shakespeare presents the early modern grammar school as a pedagogical environment characterized by active, rather than passive, learning. Newstok invokes one of the period’s key instructional texts, Richard Rainolde’s The Foundacion of Rhetorike (1563), which derived from the ancient Greek rhetorician Aphthonius’s Progymnasmata. The etymology of this word — from the Greek for ‘preparatory exercises’ — gives the sense of its instructional method, what Newstok calls ‘a regimen of mental gymnastics.’ In his account, an early modern education based on these sorts of manuals gave students ‘practice in curiosity, intellectual agility, the determination to analyze, commitment to resourceful communication, historically and culturally situated reflectiveness, the confidence to embrace complexity.’ To some degree, Newstok paints a picture of a culture that allowed learning for learning’s sake; yet the goal of these kinds of exercises was the development of linguistic skill that would, ultimately, be useful in any future vocation. ‘This was verbal training for careers,’ Newstok tells us, ‘whether in the church, the court, or the market.’”

What do Russell Kirk and Michel Houellebecq—two men who otherwise seem worlds apart—share? A belief that “without the bedrock of a living religious faith, dignity and purpose are mere constructs of the mind, subject to age and circumstance,” James Person writes in Modern Age.

Photo: Red fox

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.