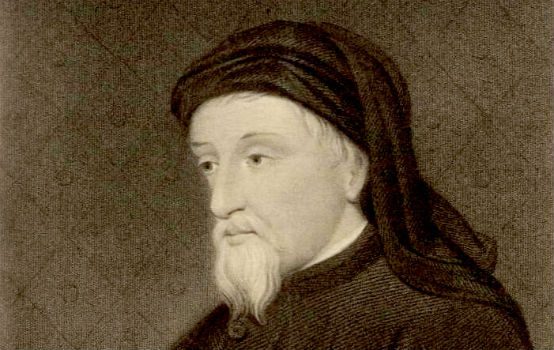

Canceling Chaucer

Good morning. The administration at Leicester University has proposed removing Chaucer and Beowulf from the English curriculum as part of its effort to “decolonize” course offerings: “Academics now facing redundancy were told via email: ‘The aim of our proposals (is) to offer a suite of undergraduate degrees that provide modules which students expect of an English degree.’ New modules described as ‘excitingly innovative’ would cover: ‘A chronological literary history, a selection of modules on race, ethnicity, sexuality and diversity, a decolonised curriculum, and new employability modules.’ Professors were told that to facilitate change management planned to stop all English Language courses, cease medieval literature, and reduce Early Modern Literature offerings.”

You gotta admire the doublespeak here: Canceling medieval literature will make the English degree more of an English degree, not less, because the new modules will offer students what they expect from an English degree: politics and vocational training.

The university has since written The Daily Mail to say they aren’t removing Chaucer because he’s white. They are removing him because he’s boring: “Leicester told MailOnline the changes had nothing to do with the texts being ‘too white’ but that it was keen to engage with ‘our students’ own interests and enthusiasms.’” They will still teach Shakespeare, they said, and one “Colston [sic] Whitehead.” Glad the folks making these decisions know what they’re talking about.

In other news: In The New Atlantis, Algis Valiunas revisits the life and work of Alexander von Humboldt: “The presiding scientific genius of the Romantic age, when science had not yet been dispersed into specialties that rarely connect with one another, Alexander von Humboldt wanted to know everything, and came closer than any of his contemporaries to doing so. Except for Aristotle, no scientist before or since this German polymath can boast an intellect as universal in reach as his and as influential for the salient work of his time. His neglect today is unfortunate but instructive.” (By the way, after you’ve read Valiunas’s wonderful piece, check out The New Atlantis’s new Projects page.)

Writers at The New Yorker go on strike—sort of: “Today, the New Yorker Union is undertaking a twenty-four-hour work stoppage. Between 6 A.M. on Thursday, January 21st, and 6 A.M. on Friday, January 22nd, union members will not participate in the production or the promotion of material for the print magazine or the Web site. We are withholding our labor to demand fair wages and a transparent, equitable salary structure, and to protest management’s unacceptable response to our wage proposal and their ongoing failure to bargain in good faith.”

French publishers and Google reach content payment deal: “Google and APIG did not say how much money would be distributed to APIG’s members, who include most French national and local publishers. Details on how the remuneration would be calculated were not disclosed. The deal follows months of bargaining between Google, French publishers and news agencies over how to apply revamped EU copyright rules, which allow publishers to demand a fee from online platforms showing extracts of their news.”

Bernie Sanders in art: “The art historian Michael Lobel made a version in which Sanders inside a moody café from Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks—itself the subject of one of the more memorable Covid-era memes—and others placed the senator within iconic works by Sandro Botticelli, Vincent van Gogh, ASCO, Joseph Beuys, and Georges Seurat.”

For Émile Zola, political power “doesn’t make you drunk, exactly: the effect is more like being bloated,” Aaron Matz writes: “His Excellency Eugène Rougon is the most straightforwardly political novel Zola wrote. Empire is rendered as a group of functionaries and strivers in the foreground, rather than (as in the other volumes) the background for some other action. When the book opens Eugène is president of the Council of State, close to Napoléon III but starting to lose his grip. He resigns after a conflict with the emperor, but his return is never far off: ‘He loved power for power’s sake, free from any vain lust for wealth or honors. Crassly ignorant and utterly undistinguished in everything but the management of other men, it was only in his need to dominate others that he achieved any kind of superiority.’ Zola’s disenchanted view of politics in this novel creates a strange effect: Eugène lacks the charisma we might expect from both a politician and the main character of a novel. Usually in the Rougon-Macquart books, the hero who wants to dominate others is driven by a kind of feral vitality: there is the department store owner who wants to crush all his rivals, the real estate speculator who will do anything to make more money, and even the bohemian painter who wants to “conquer” the Paris art world. But Eugène is strangely languorous. From the opening scene, where he is a corpulent man with droopy eyelids slumped in his seat in the Chamber of Deputies, Eugène displays an ambition that is both ruthless and lethargic. The result is a political satire less like Trollope’s contemporaneous Palliser novels than like Daumier’s caricatures of députés earlier in the century, in lithographs like Le Ventre législatif, where fat men barely manage to look up from their benches.”

The mid-career work of Cecily Brown and Inka Essenhigh: “Critics are not required to be right, merely (as Donald Judd said of artworks) interesting. But part of what makes criticism of new art potentially interesting is that it is, in part, a gaze into the future. Remember Clement Greenberg in The Nation in 1946 predicting of Jackson Pollock’s work, ‘In the course of time, this ugliness will become a new standard of beauty,’ and two years later, venturing that one of the same artist’s paintings ‘will in the future blossom and swell into a superior magnificence; for the present it is almost too dazzling to be looked at indoors.’ Most criticism, of course, doesn’t make its wagers on the future so explicitly, nor should it. Greenberg only unsheathed his crystal ball during those rare moments of highest intensity of feeling, and we should follow that example. Yet still our judgements remain hostages to fortune. Musings on the fate of judgment have been much on my mind since seeing exhibitions by a couple of painters, Inka Essenhigh and Cecily Brown, who in the late 1990s seemed to me without doubt to be among the most promising painters on the New York scene. They recently exhibited their latest efforts in New York, at the Miles McEnery Gallery and the Paula Cooper Gallery, respectively. I had to wonder: Would I find they’d made good on their promises? Had they blossomed? Or might their great potential have been more in the eye of the beholder?”

Photo: Carcassonne

Receive Prufrock in your inbox every weekday morning. Subscribe here.