Paul Kingsnorth’s Alexandria

Regular readers know that I am a fan of the writing of Paul Kingsnorth, an Englishman who lives with his wife and two children in rural County Galway, Ireland. You will recall a short piece of Kingsnorth’s fiction, “The Basilisk,” that I linked to here over the summer. I discovered his essays a few years ago — in particular, “In The Black Chamber,” on the meaning of sacredness and wonder sparked by a visit to prehistoric cave paintings in France. At the time, Kingsnorth was an atheist, but was on a quest for the eternal.

Kingsnorth spent most of his adult life in the environmental movement, but had come to believe that the fight to save the earth from climate destruction had been lost. He helped launch the Dark Mountain Project, a way of responding to the collapse through writing and art, by reckoning with what it means to live with hope in the ruins. In 2014, The New York Times Magazine profiled Kingsnorth, explaining in detail why he believes what he believes. Excerpt:

Instead of trying to “save the earth,” Kingsnorth says, people should start talking about what is actually possible. Kingsnorth has admitted to an ex-activist’s cynicism about politics as well as to a worrying ambivalence about whether he even wants civilization, as it now operates, to prevail. But he insists that he isn’t opposed to political action, mass or otherwise, and that his indignations about environmental decline and industrial capitalism are, if anything, stronger than ever. Still, much of his recent writing has been devoted to fulminating against how environmentalism, in its crisis phase, draws adherents. Movements like Bill McKibben’s 350.org, for instance, might engage people, Kingsnorth told me, but they have no chance of stopping climate change. “I just wish there was a way to be more honest about that,” he went on, “because actually what McKibben’s doing, and what all these movements are doing, is selling people a false premise. They’re saying, ‘If we take these actions, we will be able to achieve this goal.’ And if you can’t, and you know that, then you’re lying to people. And those people . . . they’re going to feel despair.”

Whatever the merits of this diagnosis (“Look, I’m no Pollyanna,” McKibben says. “I wrote the original book about the climate for a general audience, and it carried the cheerful title ‘The End of Nature’ ”), it has proved influential. The author and activist Naomi Klein, who has known Kingsnorth for many years, says Dark Mountain has given people a forum in which to be honest about their sense of dread and loss. “Faced with ecological collapse, which is not a foregone result, but obviously a possible one, there has to be a space in which we can grieve,” Klein told me. “And then we can actually change.”

Kingsnorth would agree with the need for grief but not with the idea that it must lead to change — at least not the kind of change that mainstream environmental groups pursue. “What do you do,” he asked, “when you accept that all of these changes are coming, things that you value are going to be lost, things that make you unhappy are going to happen, things that you wanted to achieve you can’t achieve, but you still have to live with it, and there’s still beauty, and there’s still meaning, and there are still things you can do to make the world less bad? And that’s not a series of questions that have any answers other than people’s personal answers to them. Selfishly it’s just a process I’m going through.” He laughed. “It’s extremely narcissistic of me. Rather than just having a personal crisis, I’ve said: ‘Hey! Come share my crisis with me!’ ”

You might think of Kingsnorth as a Gen X English Wendell Berry. In fact, he selected and wrote the introduction for a 2019 collection of Berry essays, The World-Ending Fire: The Essential Wendell Berry. You can read Kingsnorth’s selected short fiction and essays on his website here.

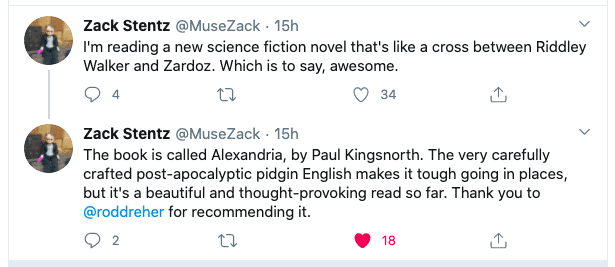

This week, Kingsnorth published his latest novel, Alexandria (Gray Wolf Press), a dystopian tale of a remnant community living in eastern England about a thousand years into the future, after the seas have risen 60 meters, and all human civilization has been destroyed. Like most futuristic science fiction, it’s really a novel about ourselves and our time. The questions Kingsnorth explores in the novel have to do with the meaning of the human person, and the struggle between the Body and the Machine. I don’t typically read fiction like this, but I found the book hard to put down, because it intersects with so many of my own concerns. I recommended Alexandria to Zack Stentz, the screenwriter of a couple of Marvel films, and sci-fi projects. He tweeted this week:

The other day, I sent Paul some questions via e-mail, and received his answers back this morning. Here’s our conversation:

Alexandria is set in a dystopian future, almost a millennium after the collapse of civilization under the pressures of global climate catastrophe. I first discovered your writing years ago, with your Dark Mountain project. Why are you so interested in apocalypse?

I think to answer that question you would have to look deep into my twisted soul! In some ways, I just have a natural tendency to see a glass half empty. But I also think it is increasingly hard to be anything but apocalyptic when we look to the future if we are being honest. I worked as an environmentalist for years, and it’s impossible to look at the current state of the Earth without foreboding. Culturally, too, it’s hard to argue that the West, or indeed much of the rest of the globe, is in a healthy place at the moment. Maybe it never has been. Still, I’m pretty convinced by the claim that we are in a cultural decadence. The divisions and the tensions are rising across the board, and we have no unified sense of what we are or where we are going or what we believe or stand for.

I tend to think that civilisations have a natural life cycle — a rise and fall — as do empires, and that the West is at the end of one of those cycles now. My country, Britain, once owned half the world, and sucked much of its wealth out for its own gain. After World War Two, we sunk into post-imperial decline, and we’ve been in that decline all my life. Your country took over the imperial mantle, and now it’s your turn to experience the collapse. This is what happens to empires, so there is some justice in the world.

This can all seem pretty apocalyptic. Something that is interesting to me, though, is the original meaning of the word apocalypse, which of course is ‘revelation’ or ‘unveiling.’ In apocalyptic times, a lot is revealed that was previously hidden. The covid virus alone is unmasking so much of the unworkable and unreal nature of modern life: it is fundamentally unsustainable in so many ways. We were living in an illusion, and now the illusion is shattering.

You believe that there is no stopping climate collapse at this point. I have said the same thing about the cultural collapse of Christianity in the West, with my Benedict Option project. We both agree, I think, that humankind needs to shed its optimism, and instead look for the kind of hope that can give resilience. This approach infuriates people. Why the rage, do you think?

Let’s look at the modern mind, and especially the modern Western mind. What defines it? I think it might be a desire for control. We are desperate to believe that humanity can build paradise on Earth. Millions upon millions of people died in the last century alone in pursuit of that goal. We believe that we are, in the words of technotopian thinker Stewart Brand, ‘as gods, and we have to get good at it.’ But we are not good at it, and we never will be, because we are not gods. We are a species which has caused a mass extinction event, changed the climate of the whole planet and turned half of the world’s ancient forests into tables and toilet paper: all in pursuit of ‘progress.’ We can create marvels, but we are not in control of where they take us. We are now at a point where we cannot stop the runaway train.

But we hate hearing this! If the modern West has a religion, it is the religion of Progress — the faith that things will continue to improve for us all as a result of our cleverness: that the arc of history bends not only towards justice but towards endless material improvement. I genuinely do believe that we have an almost spiritual commitment to this notion. Questioning it, in that context, is virtually blasphemous. It infuriates people, and they call you all sorts of names. Without progress, what do we have left?

Let’s talk about Alexandria, which is the third of a trilogy. How does it relate to your two previous novels, The Wake and Beast?

A decade ago I started writing a novel about the Norman Conquest of England in 1066. I wanted to tell the story of the largely unknown underground resistance movement which fought against the Normans. As I wrote, a problem emerged. My narrator was an eleventh century man but he was speaking 21st century English. In reality he would have spoken what we now call ‘Old English’, a Germanic language which is virtually unrecognisable to us today. I couldn’t make his voice work. What I ended up doing was creating my own version of Old English — a shadow tongue, as I called it — which was intended to convey the feel of the speech patterns of early medieval England. It was a challenge, but it was fun.

By the time I’d finished I developed the mad idea that this would be the first book in a loose trilogy which would span two millennia of time, and would trace the path of one line of people in the same place across history. My second book, Beast, was set in the present day — that was published in 2017. Alexandria is the last book in the series. It’s set a thousand years from now, in the same place as The Wake. There are a lot of echoes, but it’s also a book that stands alone. It can be read without even knowing the other two exist; but if you have read them, there will be an added layer of richness to it. The common theme of all the books is the relationship between people and the land — and the notion that the land is a lot more sentient and aware than we might give it credit for.

The first thing that leapt out to me about Alexandria is how this remnant community is organized around religion. It’s a pagan earth religion that appears to have been cobbled together from the ruins of memory — for example, the myth of the Fall of Man is a combination of the Judeo-Christian myth and the pre-Christian Odin myth. It turns out that religion is absolutely central to this novel, though Christianity has clearly not survived the collapse. Why is this novel so centered around religious practice and consciousness?

Partly because this is what I am interested in at present. All novels, even novels set a millennium in the future, are really just reflections of the writer’s inner landscape. But more broadly because of a realisation that has been creeping up on me for some years now, and which has really entirely changed my worldview: that religious practice and consciousness is central to human life, and always has been.

I grew up in a post-religious country, and as a young man I largely viewed religion as an antiquated irrelevance, if not an actively hostile force. That has changed over time, for many reasons. Studying history, and trying to work out what has gone wrong for us today, has brought me back again and again to the primary claims of any serious faith: the importance of humility, love of others, self-control and respect for creation. The fact that many religions have so often failed to practice these goals doesn’t negate their truth. My own understanding of history and other cultures, has brought me around now to almost the opposite view to the one I used to hold. Now I think that religion is perhaps the best, maybe even the only, way to direct humans towards humility rather than pride. And humility is what we need in the face of the ecological crisis we have created.

I’ve learned a great deal here from my wife, who comes from a Punjabi family. Watching some of my close family practice the Sikh religion, which at its best is a beautiful expression of charity and community, has shown me what faith can and should do; and how much better that way of life is than the kind of deracinated consumer individualism that has replaced it in the world.

Alexandria, in some ways, was designed to have this argument out at length, perhaps at least partly so that I could make up my own mind about it. Is faith a necessary component of a worthy human life, or a superstitious hangup from another age? There are characters in the novel who push both perspectives, and others.

I don’t want to give too much of the plot away, but we can say that the survival of humanity depends on how the remaining people regard the body. Why is the body so central?

The central question that runs through the novel — the question that has riven humanity and created an entirely new world — is to what degree humans should live within the bounds that nature has set for them, and to what degree they should attempt to break them and remake the world in their own image. Really, that the question has been at the centre of the human project since we planted the first crop or fashioned the first axe. Today, in the dawning age of transhumanism, it takes on a new urgency.

We now have the technologies available, or on the horizon, to resurrect extinct species, genetically modify plants and animals to create versions we find more useful and — most ominously — entirely remake the human body so that it resembles a new species; one created by us rather than by God or nature. I have met people who are thrilled by this prospect and are working to make it happen. I think it’s pretty clear that the fundamental redefinition of the building blocks of life itself is the next phase of ‘progress’. Some people find that thrilling – the final conquest of nature, if not its abolition. I find it terrifying — arrogant, hubristic, the final frontier in our war against life and against limits.

In The Abolition Of Man, C. S. Lewis wrote: ‘human nature will be the last part of nature to surrender to man. The battle will then be won … but who, precisely will have won it?’ That’s the question my book is asking.

In my own recent book, Live Not By Lies, I have written about how soft totalitarianism is coming upon us in large part because we want to use technology to be free of natural limits, and to avoid suffering in our bodies. I was startled to see these themes playing out in Alexandria too. The temptations the techno-totalitarian’s emissary offers to the remnant make a lot of sense, if suffering in the body is a curse from which one wants to be free. Religion and mythology are the only meaningful sources of resistance to this anti-human techno-totalitarianism. Is that true in our own world?

The big issue — the resounding global question, the one we are so desperate to ignore — is the reality of limits. The importance of acknowledging limits is at the heart of the green movement — or at least, it used to be. The greens today are very much a part of the global techno-machine which seeks to use technology to overcome the problems that technology has created. Back in the day though, the environmental argument was all about limits and how we could live within them. Limits to growth, limits to pollution, limits to human population size, limits to consumption, limits to behaviour: the questions were around what they should be, whether they were flexible, whether they were right or wrong and whether and how they could be enforced.

This is really, I suppose, the classic divide between the small-c conservative and the progressive minds. The conservative wants to conserve, to protect, to nurture; at least in theory. The progressive wants to move ‘forward’ to something better, to improve the world by remaking it according to our lights. Classical environmentalism was conservative in that sense. Roger Scruton wrote a thick book about this conservative vision of environmentalism; not that many conservatives were listening. They were too busy shilling for big business to bother about conserving anything. This old, rooted version of the green worldview is maybe best exemplified in your country by the great Wendell Berry, who is still down in Kentucky enunciating it. But there’s no doubt that the old greens have lost, as has anyone who wants to meaningfully conserve anything in the age of liberal techno-capitalism. Limits are now for fools and romantics and reactionaries. All problems are to be solved in one way: more, bigger, faster. In the age we live in, growth and progress are the only games in town. That’s been the case for a long time now.

I only realised relatively recently that this was actually a religious question — or at least a spiritual one — and that’s one of the great themes of Alexandria, which I was working out as I wrote it. Religions impose limits: on our desires, our passions, our will. They require us to live within boundaries, to obey God, and the best of them require us too to respect nature — Creation — and our bodies, and the shape and form they impose upon us. Religions require self-control, limits on our appetites, respect for those shapes and forms rather than a desire to break them open. Take away the notion that God wants us to live within given limits, and to exhibit self-control for the greater good, and you get the kind of free-for-all we have now in which every limit we see in any area of life is a form of oppression to be attacked and destroyed.

So the short answer is that, yes, traditional religion can be a real source of resistance to the techno-machine, though in the real world it has often completely failed to be, and has just as often helped it advance. For any path I’m aware of it though, it would seem like a requirement to stand against it. Take Christianity: it’s long bemused me that anyone who follows a man who said things like ‘woe unto ye who are rich’, and made his views on wealth, greed and cupidity crystal clear, could possibly support the existing order and its values. And if God created the world and ‘saw that it was good’ — six times! — then how can we justify mining and poisoning it for our own short-term gain?

I think we could make a convincing case that society in the West today is based on the seven deadly sins – not on avoiding them, but on pursuing them, as active goals. We have to each work out where that leaves us as individuals.

I recently participated in an online seminar about an excellent new book about bioethics, written by Carter Snead, a Catholic scholar who argues that we need to return to an older, richer view of what it means to be human. He says that the anthropology of “expressive individualism,” one that seems the human person as essentially will unencumbered by anything unchosen, is not only unrealistic, but is taking us to some dark places. I agree with him, of course, but during the seminar, I brought up Alexandria as an example of how important it is to fight these lies not just with nonfiction arguments, but with good storytelling. In fact, I think it’s more important, because the storytelling of expressive individualism is the controlling myth of our civilization — and it makes it harder for ordinary people to accept the plausibility of solid arguments like Snead’s. What kind of stories, and storytellers, do we need today, in our crisis? How can they be formed, and how can they be heard?

This was the question at the heart of the Dark Mountain Project, which I co-founded a decade ago. Dark Mountain was — still is — a cultural movement which is looking for new stories, and new ways of telling them, that will rise to this challenge. When I conceived that project I was wondering where all the fiction writing was that was really engaging with the world as it is – engaging with the crisis – rather than as we would like it to be. I wondered how much contemporary fction would look simply irrelevant to future generations: as if we were writing silly fancies while the world burned. I thought that a lot of writers, possibly including me, were in denial to some degree; still writing as if everything would be fine. Our manifesto declared that everything would not be fine and that we should tell stories as if that were true. I don’t know if we succeeded, but the work is ongoing.

Do you have religious belief and practice? What kind of religious belief and practice will we in the West need to embrace if we are going to resist the Machine?

Well, let’s first acknowledge that the West is ground zero for the techno-utopian tragedy that is unfolding around us. It’s what the Native American activist Russell Means called the ‘European mind’ that created the rational, spiritless, utilitarian world that ultimately leads us to Lewis’s abolition of man. That manifests today most obviously in the the Silicon Valley technotopians who want us to upload our minds to the cloud so that we can live forever after death in silicon transcendence – a twisted echo of the Christian story. These people are the ones who control how we communicate, and who frame our ways of seeing.

That’s another way of saying that we — modern, Western people — made this mess, but we don’t seem to know how to clean it up. Maybe we don’t want to. But we should also remember that Means’s ‘European mind’ is really the modern mind — the one which embraced rampant individualism, ‘progress’, love of money and the pursuit of the passions, all of which have eaten us from within. The cultural manifestation of that is the kind of decadent uber-liberalism you write about so penetratingly. The economic manifestation is consumer capitalism, which has destroyed cultures and landscapes worldwide like nothing before it. The ‘left’ tends to push the former while the ‘right’ shills for the latter, but they are two sides of a coin, and they both eat away at our souls.

But there was another West before modernity, just as there was another East or South before we exported modernity to the ‘developing’ world. There are still other Wests that exist alongside the main stream of progress, growth and endless upheaval and uprooting. Our challenge now, I think, is not so much to go back, which is never possible, but to go through. To go through the disintegration that modernity is unleashing and to find some better, more rooted, kinder values again on the other side of the decadence and ecological meltdown. To rediscover the deeper, better aspects of our heritage. Those would be the values of community, self-sacrifice, love of place and nature, rootedness in a sense of the sacred — and actually the baseline Christian virtues: love God and your neighbour, and really try to mean it. I’ve not come across a better ethic to live by. Again, we’re back to limits.

You ask me about my practice. I have been on an increasingly intense spiritual search for a decade, which has taken me through a long immersion in Zen Buddhism, and more recently through various forays into neo-paganism, mythology, gnosticism — you name it. Actually I think my search for some kind of objective truth goes back perhaps even to childhood. My love of nature and my desire to protect it was in many ways driven by what I think now was a religious sensibility — as I wrote in this essay a few years back.

But something was missing from all of this. It turns out that something was God. And 2020, in that respect, has been a revelation to me — literally. I found myself being dragged kicking and screaming earlier this year towards the one place I never thought to look: which is to say, to my own ancestral faith, Christianity. This is a journey that has come upon me entirely by surprise, and it’s only just beginning, so I’m not going to try and lock it down with words, or even pretend that I really understand what’s happening. But something big is going on, and it’s not my doing. I’ll just say that the world has taken on a completely new shape, and I’m still gaping at it. One day I might try and write it down.

I’m not renowned as an optimist, but actually I think that the global machine we have built will not last, because the way we are living is spiritually, as well as ecologically, unsustainable. I don’t believe now that a human culture can last for any length of time unless it has a spiritual core: unless it is built around some path to God. The paths may differ through history and across cultures, but I can’t think of a single example of a culture that has existed without one. That’s one of the themes of Alexandria: if you don’t worship what is greater than you, you’ll end up worshipping yourself. The result of our self-worship — of our rebellion — is climate change and the death of the seas. We’ll have to find a truer path, because this way of living is driving us mad and destroying the ground it stands on. But there’s a fire to be walked through first. I think we’ll emerge unrecognisable, but I think we must.

—

The book is Alexandria, published this week by Gray Wolf Press. Find links to booksellers here. Visit Kingsnorth’s own personal page for the book here. If you enjoyed this interview, take a look at this 2019 Dutch documentary about Kingsnorth, his ideas, and his life in rural Galway.