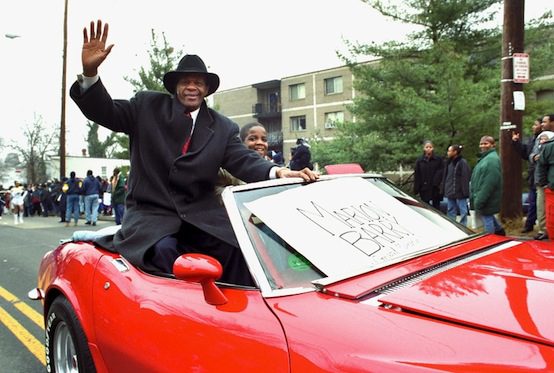

Marion Barry: D.C.’s Rascal King

The infamous former D.C. mayor Marion Barry died yesterday. Most of the obituaries and remiscences that have appeared so far are properly respectful. Even so, they can’t avoid mentioning Barry’s reputation for corruption and troubles with the law, especially his 1990 arrest on drug charges. Despite these problems, which might have doomed a lesser politician, Barry remained beloved in many parts of the city. How could citizens of the district continue to support him?

Part of the answer, as Adam Serwer points out, is that Barry was a very good politician. At the beginning of his career, he cultivated an image as an advocate for the District’s black majority, while reassuring the white elite that he was ready to do business. It’s easy to forget now, but Barry won election in 1978 largely due to votes from the Northwest quadrant. He lost much of that support when he ran for reelection. But by then he could rely on other allies.

But there was more to Barry’s success than tactical brilliance. He practiced urban politics like an old-fashioned ward boss, dispensing jobs and contracts as personal favors to his supporters. In some ways, the benefits were real: Washington’s black middle class depended heavily on municipal jobs. But they also promoted cronyism and incompetence, and helped bankrupt the city.

It’s tempting to conclude from these results that Barry was a very, very, very bad mayor. Although true in some ways, this assessment mistakes just how historically typical Barry was. If Barry had been been born white, in a different place, and in 1876 rather than 1936, he would likely be remembered as a lovable rogue, who used government to help out people to whom other roads out of poverty were closed.

There is no better exemplar of this type than James Michael Curley, the four-time mayor of Boston, Congressman, Governor, and two-time jailbird immortalized by Spencer Tracy in “The Last Hurrah“ (based on Edwin O’Connor’s novel). As Jack Beatty shows in his riveting biography, from the beginning of his political career before World War I to its end in the 1950s, Curley used government as an instrument in his lifelong mission to improve the lives of Boston’s Irish working class.

Setting a pattern that Barry would follow, Curley started out as a reformer. As challenges to his autocratic practices emerged, however, Curley relied increasingly on appeals to ethnic resentment and a bullying, macho style. In his 1942 Congressional race agains the Brahmin Thomas Eliot, Curley asserted that, “There is more Americanism in one half of Jim Curley’s ass than in that pink body of Tom Eliot.”

Curley’s divisive rhetoric was coarse but not very harmful in itself. Much worse were his policies, which relied on ever-increasing property taxes to pay for public-sector jobs. Boston boomed along with the rest of the country in the 1920s. By the time Curley left office, however, it had entered a decline from which it emerged only under the late Thomas Menino, who broke Curley’s record as Boston’s longest-serving mayor.

Like Barry, then, Curley was by objective standards a lousy mayor (particularly in his later terms). Nevertheless, he remained a hero to his people, who turned out in the thousands at his funeral. Were they sentimental about Curley’s big achievements, such as the construction of the municipal hospital? Grateful for the cash envelopes and no-show jobs Curley distributed around election time? Or unaware how Curley had damaged their city?

The answer probably involved all of these elements. Even in combination, however, they’re inadequate to explain Curley’s role in Boston. Rather than a conventional politician, Curley was a kind of tribal chieftain. More than any particular benefits, he offered his followers the sense that there was someone in power who was like them, who cared about them, and who would do whatever he could to help them.

Before World War II, there were plenty of white chiefs in the Curley mode, among rural Southerners as urban immigrants. By the ’70s, however, urban politics had been so thoroughly racialized that personal leadership and endemic corruption were seen as black pathologies rather than the historical norm. In the final analysis, Barry was a crook who hurt his city. But his greatest crime was being born black and too late to be crowned a “rascal king”.

Samuel Goldman’s work has appeared in The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal, and Maximumrocknroll.