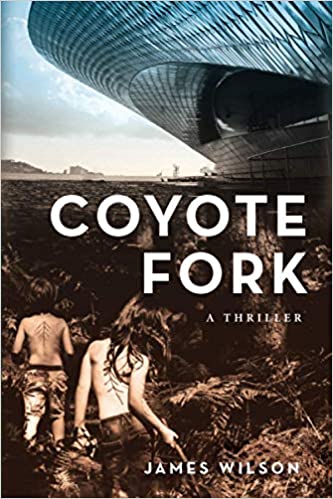

James Wilson’s ‘Coyote Fork’

The English novelist James Wilson’s latest work, Coyote Fork, is a taut thriller about a British journalist who finds himself in Silicon Valley, on the trail of killers. What he and his traveling companion Ruth — a philosophy professor who is being severely harassed by a woke student mob — discover is a mystery that has to do with nothing less than what it means to be human. I found myself unable to put the book down, not only because Wilson keeps the action moving propulsively forward, but also — indeed, mostly — because like in Umberto Eco’s The Name Of The Rose, the search for the truth of what happened to a dead person takes the protagonists on a philosophical, even metaphysical, journey. It’s a journey that has everything to do with the way we live today, in a culture dominated by Big Tech.

I e-mailed Wilson at his home in London, and asked him if he would be willing to answer some questions about the novel, published last year by Slant Books. He kindly agreed, and e-mailed his replies. The interview is below. The last question brought a response from James, about his religious beliefs, that surprised me!

RD: The themes of Coyote Fork — techno-utopianism and progressive cancel culture — could hardly be more timely. What made you decide to write about them?

JW: Like many people during the last decade, I found myself becoming increasingly uneasy about the power of the Internet (though that didn’t stop me using it!). Then, a few years ago, two developments tipped that unease into outright alarm. One was observing the impact of social media on people close to me: how it narrowed sympathies, heightened intolerance, changed decent human beings into self-righteous bullies. The other was an apparently trivial personal experience: travelling home after dinner with some friends in north London, I happened to look at my smartphone. There, blazoned across the screen, was a weather forecast for Sofia. I have never been to Sofia. I had no plans to go to Sofia. But one of our hosts that evening is Bulgarian. I could only conclude that Google hadn’t merely tracked my whereabouts, but in some sense “knew” who I was with.

I decided to dig deeper, to try to discover more about our new Tech masters. What I found convinced me that we are in the middle of the most momentous and far-reaching revolution in human history. Beneath the mesmerising surface spectacle – the Zoom calls, the breath-taking graphics, the instant streaming of any piece of music you want, the excited chatter about colonizing Mars – something much more fundamental was going on. And to me, anyway, that something is profoundly disturbing.

At its heart is the question of what a human being is: a) a complex physical-spiritual entity with a soul, reason, imagination, moral agency; or b) a meat computer, whose reality can be reduced to the data it produces, and which can be re-programmed at will by changing its software? For Silicon Valley the answer is plainly (b).

Here, for instance, is Google’s Director of Engineering, Ray Kurzweil, speaking in a Rolling Stone interview in 2016: “A person is a mind file. A person is a software program — a very profound one, and we have no back-up. So when our hardware dies, our software dies with it.”

And Kurzweil is devoting massive resources to trying to solve that problem. Many of us, he predicts, will soon be part-cyborg, a hybrid of human and machine. By 2050, he believes, we will have reached what he calls a singularity, the moment when a computer-based super-intelligence surpasses our collective intellectual power, and our only hope of survival will be to transcend the “limitations of our biological bodies and brain” and merge ourselves with it. By uploading our “mind files” to the new man-made deity, we will then be able to enjoy (?) a kind of immortality.

Some bit of me can’t help admiring people like Elon Musk and Ray Kurzweil, and warming to their enthusiasm, their audacity, their extraordinary energy. Compared with the last crop of scientists who dominated the airwaves, the New Atheists – who kept picking philosophical fights they couldn’t win, and scolding the rest of us for being so stupid – the giants of Silicon Valley are not only awe-inspiringly brilliant, but appear refreshingly positive and optimistic. But the vision of the future to which they are leading us terrifies me.

And so does the fact that it has attracted so little coverage. Because, to me – given Big Tech’s global reach and unprecedented power to shape behaviour – it seems the most urgent issue of our time. If Dostoyevsky were alive today, I’m pretty certain that it’s what he would be writing about. But I hadn’t seen any contemporary novels tackling the implications head on – so in Coyote Fork (you can’t fault me for lack of ambition!) I wanted to try to fill the gap. And I hope that, for all the seriousness of the subject matter, it still delivers some of the very un-Big Tech pleasures of a good thriller…

It is one of the signal horrors of our time that students get furious at professors who advocate for free thought and skepticism. Coyote Fork’s Ruth Halassian is horribly hounded by the woke mob. What is behind this?

There are many factors at work here, some of which I touch on in my answers to other questions. But a large part of the problem, I think, stems from a crisis of language. As a culture, we no longer agree what words are, what they refer to, what they are for. Instead, we have three more or less contradictory ideas floating around in the ether. Until relatively recently they were able to (sort of) co-exist, but they have been weaponized by the culture wars.

Idea number one – which dates back at least as far as the Middle Ages, but which came to fruition in the “linguistic turn” at the end of the nineteenth century – questions whether language can actually tell us anything objectively true about the world “out there”. It casts doubt, in fact, on whether the world “out there” is knowable to the human mind at all. This, obviously, is enough on its own to weaken the old liberal humanist vision of higher education as a collaborative venture between student and teacher to establish a truth that transcends personal opinion or preference.

Idea number two is the belief associated with thinkers such as Michel Foucault that language is a means by which the powerful in a society assert and maintain their privilege. If you accept that, and your aim is to overturn what you see as the old order, then obviously you will try to seize control of the language yourself, and assign new, revolutionary meanings to it. Once you have done so, you can then systematically punish those deplorables unaware or stubborn enough to persist in speaking as if they were still living under the ancien regime.

There is an odd similarity here to the petty – and often hurtful – linguistic code that was still embedded in the English class system when I was growing up. If, e.g., you heard someone saying “serviette” it not only connoted a piece of cloth or paper for wiping your mouth on, but instantly identified the speaker as “non-U”, because the “U” usage was “napkin”. Only now, of course, the solecism of saying “coloured person” rather “person of colour” can lead, not merely to embarrassment, but to ostracization – and, if you are a professor or a journalist, even, perhaps, to the loss of your job.

The third idea derives from the analogy, almost ubiquitous in Silicon Valley, between human beings and computers. Seen from this point of view, a word or a phrase is no more than a modular bit of code, which – irrespective of context or intention – has an immutable meaning, wherever it is slipped to place. So it makes no difference whether you use the n-word angrily to disparage someone, or in a reflective question about whether it is ever legitimate to use the n-word: in both instances, it carries the same toxic weight, and you bear the same responsibility for uttering it.

Put all those ill-assorted ingredients together, add the all-too-human enthusiasm for shouting “Crucify him!”, and you have the situation poor Ruth Halassian finds herself in.

What is gnosticism, and what role does it play in your plot?

You recently cited an excellent piece on Gnosticism by Edward Feser, which gives a very clear answer to the first part of your question. I would urge anyone interested in how the Gnostic mentality has (re-) entered the contemporary scene to read it.

But, to respond briefly on my own account: although it has historically taken many different forms, Gnosticism – in my understanding – is characterized by the belief that the material world is inherently evil. Typically, it is seen as the creation of a wicked demiurge, such as the Cathars’ Rex Mundi. (I should say, in passing, that I don’t find that a totally incomprehensible conclusion, in view of the suffering we see around us.)

Since, from a Gnostic perspective, most people are blind to this baleful state of affairs, knowledge of the truth (the gnosis) is confined to a small elite of initiates, who pass it down from one generation to the next. The ignorant masses live out their lives irredeemably deceived. The elect devote themselves to esoteric practices designed to free them from the grossness and corruption of Rex Mundi’s handiwork – including, of course, the appetites and instincts that are part of our bodies’ biological inheritance. The aim is eventually to cast off the shackles of the flesh altogether and become pure spirit.

You can see a lot of these tendencies in the ’70s commune I describe in the book. Some people, I think, tend to imagine life in a hippie commune as being a kind of endless drug-fuelled orgy, but in reality – certainly in the commune on which Coyote Fork was very loosely based – it could be extremely hard. And not just physically – although the weather, the isolation, the travails of trying to learn how to farm from scratch certainly took a toll – but emotionally, too. There was a high rate of attrition: what sustained those who stuck it out, I think, was the belief that they were finally breaking free of the chains that had constrained earlier generations, and still constrained the mindless conformists of “straight” society. In some ways, the whole venture was a spiritual rebellion against the pitiful limitations of the human individual. In the face of jealousy, possessiveness, rivalry, anger, neediness – the heroic pioneers were determined to press on regardless along the path of purity.

As I point out below, much of the Gnostic bent of the hippie movement fed through into the culture of Silicon Valley – in particular, the obsession with transhumanism. And, without giving too much away, it is very much in evidence in the character of my tech titan Evan Bone, and in his social media platform, Global Village.

Coyote Fork is the name of a failed hippie commune in northern California. What is the connection between the Sixties communes, and today’s techno-utopianism?

It’s huge. Though a lot of people still, I think, find it surprising, the two phenomena are inextricably intertwined. In fact, today’s Silicon Valley culture is, to a great extent, the improbable love child of, on the one hand, hippie communalism, and, on the other, Ayn Rand’s rampant individualism.

A key figure on the hippie side of the family is Stewart Brand, who in the late 1960s created The Whole Earth Catalogue (described by Steve Jobs as “one of the bibles of my generation”). Brand believed that the advent of the personal computer would liberate humanity from the hierarchies – education, corporations, the military – that had traditionally monopolized power and information, and lead to a historic democratization of knowledge. Many of the nascent tech giants took this as a raison d’être for what they were doing, while at the same time absorbing several of Brand’s other ideas. Particularly important to the way they developed was a belief in “the wisdom of crowds” – which meant that collaborative innovations were preferable to those produced by one individual – and a blasé disregard (still evident in Google’s attitude towards copyright) for private property.

Interestingly, Brand also promoted the notion that “America Needs Indians”. In practice, that often resulted in the members of communes turning to “Indians” – like the character of Many Rivers in Coyote Fork – who would tell them what they wanted to hear.

For anyone interested in exploring these connections more deeply, I would strongly recommend Franklin Foer’s revelatory – and very readable – World Without Mind.

Robert and Ruth are quite paranoid as they move across the landscape searching for answers in what might be murder cases. People who don’t follow the world of surveillance capitalism closely may not realize that you didn’t invent this capability as a plot device. Explain.

You’re absolutely right: a lot of people don’t realize – as evidenced by the number of times I’ve heard Coyote Fork described as “dystopian”.

As long ago as 2010, Eric Schmidt, then Google’s CEO, told an interviewer, “We know where you are. We know where you’ve been. We can more or less know what you’re thinking about.”

And since then, Silicon Valley’s ability to plunder the insides of our heads has only grown – exponentially. Every time we search online or use a smart device, we are automatically relaying intimate details of our lives to tech companies, who can now predict – with alarming accuracy – what we’re going to buy, where we’re going to go, who we’re going to meet. Increasingly sophisticated algorithms (like the “Tolstoy” Program in Coyote Fork) aim to unlock the secrets of our subjective experience and convert them into a commodity that can be sold, and used to anticipate and control our actions in ever-more minute detail. To quote Eric Schmidt again: “The plural of anecdote is data.”

This pithy assertion – which reminds me of Stalin’s alleged comment, “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic” – isn’t, I think, simply a matter of commercial calculation. It is the instinctive response of an institutional culture that overwhelmingly fears and distrusts the autonomous world of the imagination – a world that (the ultimate insult!) cannot be measured. By reconfiguring our inner lives as data, that fatal flaw can be overcome, and Palo Alto can breathe easy again, confident that the deepest truth of someone else’s personal experience is what can be said about it from the outside.

So the assault on the privacy of the final redoubt, our own minds, is gathering pace. New face recognition software promises to decode, not merely whether or not we are lying, but our sexual orientation and political views (a big deal, when – as you have been presciently telling us for years – holding the “wrong” political views can now have dire professional and personal consequences). And over the past few months, scientists at Queen Mary’s University in London have developed a system using “neural networks” – which replicate some of the functions of the brain – to decipher people’s emotions via radio antennae.

We can’t say we haven’t been warned. If this is not the way we want to live, we had better do something about it – now.

You posit the Native Americans who have been displaced by wealthy whites as anti-Gnostic. I’m sure some woke reviewer might say that you are being patronizing, but in fact you have spent much of your career advocating for aboriginal tribes, and understand their world. What do they have to teach us?

This is an enormous question (I wrote an entire book on Native American history, The Earth Shall Weep, and still feel I have more to say on the subject!). And it’s also a question that anyone who has worked with indigenous people gets asked a lot – often prompting a set of entirely predictable off-the-peg responses. So I’m going to answer a slightly different question: What have they taught me?

Of course, Native American communities are hugely varied, both culturally and historically. They are not – and never have been – perfect models of prelapsarian bliss: they are prey to all the ills – anger, jealousy, greed, dysfunction, cruelty – of humans everywhere. In many cases, their problems have been grievously exacerbated by (sometimes well-meaning, but usually insensitive, and often brutal) attempts to suppress their languages and religions, transform their ways of life, rewrite the stories by which they understand who they are. (It seems to me this in some ways parallels the assault that many Conservatives feel the Left is now visiting on them, with exactly the same rationale: It is ordained by progress.) Many are plagued with poverty, drug and alcohol abuse, high rates of suicide and accidental death.

But, with all these qualifications, most Native American communities, in my experience – at least, most of those striving, like the little group in Coyote Fork, to hold on to their own value system – share several characteristics that set them apart from much of the larger, non-native society.

One, they believe that they are the work of a creator. Two, their stories tell them that they were placed in a particular landscape, for which – and for the other beings with which they share it – they have some responsibility.

Three, their cultures lay great stress on truth-telling. Language is important: use it recklessly or dishonestly, and you risk disrupting social harmony. I am frequently struck, when I go from the non-native world into an American Indian community, by how much more often I suddenly hear the phrase, “I don’t know”. In their experience, merely sticking another label on something doesn’t change its essential nature. (In some communities, this led to resistance to the substitution of the politically correct “Native American” for “Indian”. Many, many native people still call themselves “Indians”, when the term has all but vanished from polite usage in the wider society.)

Four, there is always laughter in native communities, and much of it derives from what the indigenous writer Gerald Vizenor calls “the Native Tease”. (E.g., the group I visited after my trip to Silicon Valley, teased me – and each other – about the pallor of my skin, and the various gradations of brown in their own, in a way that would have made the latter-day puritans of Palo Alto blench with horror.) Of course, teasing and laughter are not peculiar to native people. But they do appear to be remarkably lacking in the world of Big Tech, and in the rampaging online mobs which Big Tech has armed.

(It’s always perilous trying to define humour – but in many cases, it seems to me, it is a way of acknowledging, and perhaps defusing, the tension between two contrasting realities. But for that to work, the realities have to be – like the different shades of skin colour – unalterable givens. And the native world is full of unalterable givens – many of them difficult and painful.

The Big Tech world, by contrast, appears to recognize no unalterable givens at all. Every myth is there to be busted, every old way of doing something to be destroyed, every limit to be transcended. No two things are solid enough, or stay still long enough, to be a source of humour – even if you were willing to risk censure by laughing at the difference between them. So what Silicon Valley has instead is fun: plastic furniture in bright primary colours, romper room play areas, free ice-cream. Not the same thing.)

Five – and finally – native people tend to see as normal aspects of human experience that we would categorize as “paranormal”. This acceptance stems from a vision of the world, not as inert matter, but as a living entity, and as home to – or interpenetrated with – spiritual forces. Not all those forces are always benign – they can be dark and destructive – but recognizing them, and learning to co-exist with them, is a crucial part of being human.

This last point, in particular, chimes with my own deepest intuitions, but – growing up, as I did, in a post-war Britain that was predominantly kind, safe and decent, but truculently hostile to anything that challenged “common sense” – I found myself, for much of the time, in a minority of one. So it was a huge relief to realize, when I finally reached Indian Country (in case that phrase makes you nervous, the main native newspaper in the U.S. is still called Indian Country Today) that I was not, after all, alone.

Of course – as you suggest in your question – people may accuse me of presenting a romanticized picture. But if it is, it’s a romanticized picture based on spending time in scores of different native communities over more than forty years. In the end, the most any of us can do is speak from our own experience. And my experience is that some of the most intense moments in my life, the moments when I have been most profoundly aware of what it is to be human, have been in those communities.

And, for me, the contrast those communities make with the world of Palo Alto could not be starker. On the one side, you have an elite society of Gnostic wizards, for whom California – indeed, the earth – is no more than an expendable launchpad to send the elect on the first stage of their journey into space; on the other, a group of people who are at home in the place for which they were created, and must do everything in their power to protect it.

Two of the best novels I’ve read in the past year — your realistic thriller Coyote Fork and Paul Kingsnorth’s futuristic dystopia Alexandria — are very different novels by two British writers, both of whom write about the consequences of modern Gnosticism. Paul, who has been a religious seeker for some time, took a strong religious turn after finishing Alexandria, and has become an Orthodox Christian. What is the source of your hope?

Strange as it may seem – or perhaps it’s not strange at all – I too am an Orthodox Christian convert. My wife Paula and I are part of a small Orthodox community in south London founded with the blessing and encouragement of the late Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh.

This isn’t the place to detail my own tortuous spiritual/religious journey: I will only say that, when I see the radiance and serenity of some of our fellow-parishioners at the liturgy, I wish my faith were more like theirs. There are four lines from a poem by Czeslaw Milosz called “Distance” that resonate deeply with me:

There are so many who are good and just, those were rightly chosen

And wherever you walk the earth, they accompany you.

Perhaps it is true that I loved you secretly

But without strong hope to be close to you as they are.

I do, nonetheless, find in Orthodoxy a great – and growing – source of strength and joy. Its beauty; its rootedness; its sense of wonder; its humility in the face of mystery; its concern for the salvation, not only of individual souls, but of the whole of creation; the way its disciplines are incarnated in our bodies, saving us from the illusion that we are pure spirit – all these things, taken together, make it a solid foundation, a base from which to face whatever is coming.

And for me, the act of writing is itself a deep source of hope. ‘Writing,’ as my editor at Slant, Greg Wolfe, says, ‘is not “self-expression.” It is about doing justice to reality.’ And that – for all the disappointments and failures of the writing life – is what I sense I was put here to do.

In the midst of all the gloom, I take great heart from the human capacity to seek and respond to truth and beauty – a capacity that, to me, offers one of the most powerful arguments against the reductionist view that we are merely the product of a blind struggle for genetic survival. And to feel a vocation to try (however inadequately) to bear witness to the truth is to acknowledge that one was brought into existence by some purpose infinitely larger than one’s own purposes. I may never entirely grasp what that larger purpose is – but at least I feel I know what I have to do to serve it.

—

James Wilson’s Coyote Fork is available in hardcover, paperback, and Kindle e-book. If you would like to know more about the author, or even to contact him, visit James Wilson’s homepage.