In Defense of Howard Zinn

I discovered the valuable and necessary work of Howard Zinn during my junior year of high school. My history teacher—a man dedicated to pedagogical excellence who is now the principal of my alma mater—assigned Zinn’s chapter on the murder, expulsion, and theft of Native Americans as a counterpoint to our textbook’s deceptively incomplete and sunny account of 1492.

After 17 years of nationalism, triumphalist stories of American pride and progress, and the routine vilification of everyone from the indigenous to the Vietnamese that imperial pom-pom waving requires, Zinn’s “alternative” narration was riveting—and it had the benefit of being true.

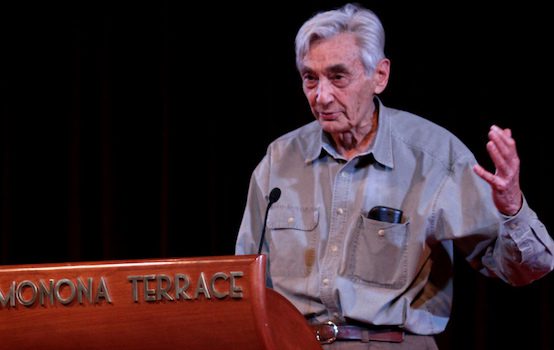

Gilbert T. Sewall recently critiqued Zinn here at The American Conservative, yet for all his eloquence, he never quite assesses the historicity of Zinn’s account. In his condemnation of Zinn’s influence on academia and popular culture, along with his speculation that Zinn’s primary motivations were celebrity and self-aggrandizement, he pauses only to quote other writers and scholars who share his distaste for the deceased historian and Boston University professor.

Sewall writes of Zinn’s posthumous life: “First popular with the general public, not historians, [A People’s History of the United States] has gradually turned into a cardinal source for academics, book editors, and film producers.” Then, as he climbs toward his conclusion, Sewall makes an odd but admirable concession that subverts much of his criticism: “Just because Zinn called attention to America’s shortfalls does not mean they are invented or false.”

If Zinn’s scholarship detailing America’s injustices, to use a more accurate word, is truthful, than what are we arguing about? Is it dangerous to evaluate and dictate the factual record because we fear the effect it will have?

Mitch Daniels, the former governor of Indiana, where I live, attempted to remove Zinn from K-12 classrooms. He is currently the president of Purdue University, leaving one to wonder whether he is still acting aggressively against books he considers, in his academic parlance, “crap.”

Those who bemoan Zinn’s popularity might want to take a course in irony. It is because of censorship campaigns, such as the one Daniels tried to administer, that Zinn developed his charisma of excitement and rebellion. When I first read his work, I felt as if I was breaking through a conspiracy to keep me misinformed.

Rather than an academic Kardashian, Zinn seemed like a true believer in the populist necessity of exerting control over the reckless and arrogant application of power. As even Sewall admits, the United States did mistreat and exploit many different people, from its own citizens to newly arrived immigrants and foreign subjects of conquest, throughout its history. Given the contradictory character of that history, the fuel of democracy, that fire from down below that Zinn explored and encouraged, was and remains necessary to extend the beautiful and noble American idea of “liberty and justice for all” to those its leadership too often excludes.

Zinn begins his memoir, You Can’t Be Neutral On a Moving Train, with an illustrative anecdote about an appearance he made at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. An audience member asks, “Why do you live in this country?”

I felt a pang. It was a question I knew people often had, even when it was unspoken. It was the issue of patriotism, of loyalty to one’s country, which arises again and again, whether someone is criticizing foreign policy, or evading military service, or refusing to pledge allegiance to the flag. I tried to explain that my love was for the country, for the people, not whatever government happened to be in power. To believe in democracy was to believe in the principles of the Declaration of Independence—that government is an artificial creation, established by the people to defend the equal right of everyone to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness…. When a government betrays those democratic principles, it is unpatriotic. A love of democracy would then require opposing the government.

Zinn was by his own admission a radical leftist, but it is baffling that his conservative critics are largely oblivious to how his work might also benefit their political enterprise. What better argument for a small state exists than a full accounting of government’s atrocities and errors?

The story in Zinn’s memoir continues with descriptions of the inspiring people Zinn met at a campus dinner before his lecture. A campus parish priest—“built like a linebacker”—gave Zinn a one word answer when the historian asked him why he dedicated his ministry to the advocacy of peace and civil rights: “Vietnam.” He was a combat veteran who had entered the seminary after making it home in one piece. Then there was the student who had recently graduated with a degree in nursing and was providing medical care to peasants in Central America.

Zinn observes: “It is remarkable how much history there is in any small group.”

Even if it occasionally stinks of anti-intellectualism, the conservative caricature of academia as a bizarre subculture of insect politics and unintelligible jargon does contain elements of truth. Zinn, in delightful contrast, took his Ivy League education directly to the people, traveling far outside his department building to excite and energize graduate students and autodidacts alike with—yes—his own interpretation of American history.

It’s easy but unfair to give the impression that Zinn was merely an academic to the stars because of how Matt Damon has championed his work and Pearl Jam has quoted him in song. As Zinn would undoubtedly insist, there are many more stories to tell outside the provinces of the rich and famous.

Bonnie Tsui is an outstanding writer whose book American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods won the 2009-2010 Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature for its rich telling of the history and contemporary life of Chinatowns in American cities. When I asked her if her subtitle reveals any intellectual kinship with Zinn, she said, “Perhaps it’s fair to say that we shared a strong desire to tell the more difficult, less-heard stories of our country’s history, with emphasis on perspectives and lives that previously had not been given equal weight, or perhaps had been considered outside the mainstream experience.”

In his own explanation as to what a “people’s history” is, Zinn wrote, “It is a history disrespectful of governments, and respectful of people’s movements of resistance.” Sewall describes Zinn’s admission of bias as arrogant, but in full context it reads as a declaration of honesty and clarity of intent: “The mountain of history books under which we all stand leans so heavily in the other direction—so tremblingly respectful of states and statesman and so disrespectful, by inattention, to people’s movements—that we need some counterforce.”

A credible argument against Zinn might accuse him, in his mission of sociopolitical passion, of providing a one-sided and extreme account of the American story. Certainly, some governments, some leaders and officials, are worthy of respect, even admiration.

The entire educational pursuit, however, benefits from the Hegelian dialectic, and given the factuality of Zinn’s account, it would be ignorant to exclude his work from the search for synthesis.

To lay the contemporary American crises of disunion and despair at the headstone of Howard Zinn is more extreme and biased than anything one will find in A People’s History of the United States. If Zinn’s influence was as strong as Sewall and other critics imagine, the overwhelming majority of the American public might not have marched obediently, like wooden soldiers, alongside the Bush administration as it invaded Iraq without just cause.

If we truly lived in the “America that Zinn made,” as the headline of Sewall’s essay suggests, it is difficult to imagine the inauguration of Donald Trump. The creeping anti-intellectualism, militarism, and worship of wealth so prominent throughout American culture cut against everything that Zinn sought to promote.

In his afterword to A People’s History, Zinn not only explains his “bias,” as I quoted above, but issues a direct challenge to intellectuals. While comparing America’s system of too much “money, weaponry, and control of information” in the hands of a small elite to a prison, he writes, “We readers and writers of books have been, for the most part, among the guards.”

“If we understand that,” he continues, “not only will life be more satisfying, right off, but our grandchildren, or our great grandchildren, might possibly see a different and marvelous world.”

The America that Zinn made would not be utopia, that much is true. But it certainly wouldn’t be whatever exists right now.

David Masciotra is the author of four books, including Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky) and Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing).