How to Reform Republican Foreign Policy

Can the Republican Party’s foreign policy be saved? Or, at the very least, can the conservative foreign-policy establishment be reformed? As the question was debated last week, violence intensified in Gaza, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 was shot down in Ukraine, and Iraq smoldered.

The welcome fact that a growing number of conservative thinkers and writers—along with a not insubstantial slice of the Republican base—judges George W. Bush’s foreign policy a failure may be a prerequisite for reform. But it is not sufficient for reform by itself.

For an aging conservative movement that has lacked a unified sense of purpose since the end of the Cold War, with the brief exception of a few years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the terror unfolding throughout the world can be massaged to fit a familiar, almost comforting script.

Israel is being attacked by her enemies. The Russian bear is on the loose. After the sectarian fighting in Iraq finally subsided toward the end of the Bush administration, the troubled country seems to be flying apart under his Democratic successor.

The narrative that the world is ablaze due to Barack Obama’s retrenchment, retreat, and penchant for leading from behind has a certain appeal. This is what happens, the argument goes, when the United States is governed by someone who is ashamed of American power.

All of this is a vast oversimplification, obviously, but busy voters don’t pore over Stratfor global intelligence reports when trying to make sense of the news. To many conservatives, this description of an often violent and seemingly chaotic world does the job as well as any competing explanation.

It is true that many big Republican donors are more hawkish—and less chastened by Bush-era failures—than the Republican rank-and-file. As Justin Logan put it in The Federalist, “the portion of the GOP donor class that cares about foreign policy is wedded to a militaristic foreign policy, particularly in but not limited to the Middle East.”

But it is equally true that even today the arguments marshaled by reflexive hawks hit the right emotional buttons for the Republican grassroots in a way that more dovish conservatives’ appeals for caution, prudence, and restraint frequently do not. They easily position themselves on the side of America—freedom conservatives!—while those who disagree are apologists for Vladimir Putin and Iranian mullahs, perhaps even “friends of Hamas.”

Glenn Beck has conceded the Iraq invasion was a mistake. Fox News’s Megyn Kelly aggressively challenged Dick Cheney on the war—“Time and time again, history has proven that you got it wrong as well in Iraq, sir”—and literally laughed at Dinesh D’Souza, who has tended to blame our foreign-policy problems on Kenyan anti-colonialism.

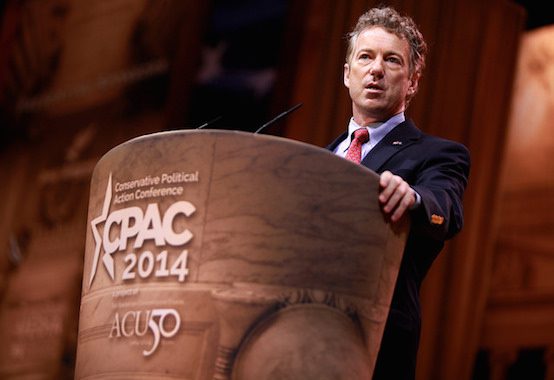

When it comes to people taken seriously by mainstream conservatives arguing that what went wrong in Iraq should guide U.S. foreign policy today, however, Rand Paul is practically by himself. (His father doesn’t have as broad an appeal among Republicans and most other Paul-aligned lawmakers are either more muddled on foreign policy or much less well known.)

Paul is doing the right thing by pointing out that our mistakes in Iraq are more Cheney’s than Obama’s, but he is taking a big political risk. As Ben Domenech points out, “the real danger for Paul” is not the dog-eared isolationism card but “to be tagged as no different from an Obama-Kerry liberal.”

The charge is absurd, even in the most literal sense. Obama initiated a war in Libya with even less congressional input than Bush had on Iraq and which was, on a much smaller scale, a comparable fiasco. John Kerry, famously for it before he was against it, of course voted for the Iraq war.

But partisanship is what makes the world of politics go round, and for most Republicans it makes sense to pretend the surge retroactively saved the Iraq war and everything was fine until Obama pulled out the troops. (To the extent the surge actually did succeed—by creating conditions that allowed the U.S. to withdraw without humiliation and giving the Iraqi government a chance, however small—it wasn’t the success its supporters envisioned.)

Paul has worked hard to make anti-interventionist arguments accessible to the Republican base while also differentiating himself from the neoconservative caricature of a functional pacifist (even if the latter sometimes annoys his foreign-policy allies).

Paul has also joined the debate over Ronald Reagan’s legacy, not because Reagan was a noninterventionist but because Republican presidents like him—from Eisenhower to Bush 41—received advice from a more diverse set of foreign-policy voices than dominate GOP circles today and did not always listen to the most hawkish among them.

It’s a winnable debate, but Rand Paul like the United States cannot go it alone.

W. James Antle III is editor of the Daily Caller News Foundation and author of Devouring Freedom: Can Big Government Ever Be Stopped?