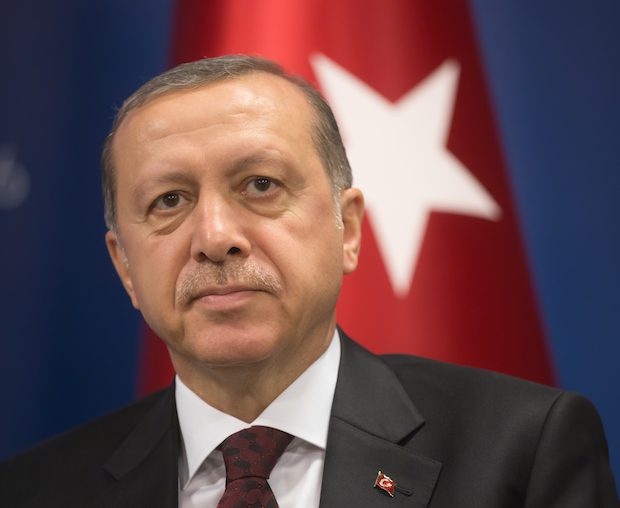

Erdogan’s Iron Fist Comes Down on Democracy and Religious Liberty

No tourist misses Hagia Sophia when visiting Istanbul. Originally an Orthodox church—the largest in the world for almost a millennium—it became a mosque after Sultan Mehmet II conquered Istanbul in 1453.

A half millennium passed when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who founded the Republic of Turkey out of the rubble of the Ottoman Empire, allowed archaeologists to uncover the church’s original wall mosaics and floor decorations. The restoration served Ataturk’s desire to promote secularism in Turkey and improve relations with West, including Greece. In 1934 Hagia Sophia became a museum.

Ataturk’s secular republic survived until the rise of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, whose Justice and Development Party, or AKP, took power in 2002. Erdogan has steadily dismantled Turkish democracy, long a weak institution bedeviled by frequent military intrusions in politics.

Originally Erdogan, a serious though not radical Muslim, posed as a reformer and the status of religious minorities improved. However, as the 2000s came to an end AKP rule changed—moving in a more authoritarian, corrupt, and Islamist direction.

He has repeatedly played the nationalism card for political gain. His plan to return Hagia Sophia to Islamic worship, unveiled last year after he found himself under political pressure again, looks equally cynical. Last week the building reopened to massive crowds, with Erdogan and many members of his government present.

This ceremony was a dramatic coda to what turned out to be the very brief Kemalist experiment. The latter was ugly in its own way: Islamic believers were restricted in living their faiths. Moreover, the regime persecuted anyone who defied its vision of Turkish nationalism, including Christians, atheists, liberals, and non-ethnic Turks. Nevertheless, today Kemalism is widely missed.

Despite the anguish understandably felt by many Orthodox believers, Hagia Sophia’s conversion alone does not violate religious liberty: Christianity has not been practiced there for more than 500 years. However, the church’s neutral museum status respected the faith displaced by war and the faithful who suffered so much. Christians may have made up as much as a quarter of the population of the Ottoman Empire. War-time persecution and massacres and post-war political collapse and territorial dissolution resulted in a smaller, more Islamic Republic of Turkey. Under extraordinary pressure that nation’s Greek community dwindled over the years.

Worse, Hagia Sophia’s conversion is merely the latest step in a larger intolerant process set in motion by Erdogan. “Many people believe that this is the result of the Islamization and nationalization of politics in the last five years,” observed Yetvart Danzikyan, editor-in-chief of the Armenian newspaper Agos, “and they find this concerning.” As they should.

Erdogan was elected mayor of Istanbul as a member of the Welfare Party, an explicitly Islamic party, which was banned in 1998 by the Constitutional Court, acting at the military’s behest. The armed forces recognized Erdogan’s popularity and had him imprisoned for reciting a nationalist poem at a rally. After his release he helped create the AKP, which went on to win the 2002 election against a gaggle of discredited secular parties.

Since then the AKP has won every election, albeit sometimes by a slim margin and through an increasingly unfair electoral process. Observed journalist Mustafa Akyol, now living in America and affiliated with the Cato Institute: the AKP has become “a parochial, paranoid and authoritarian party which sees conspiracies by the West and its imagined fifth columns under every stone.”

In just the last day, Turkish lawmakers acting on behalf of Erdogan, passed sweeping legislation to control and regulate social media. Among other measures, platforms with over a million users (Facebook, Twitter & You Tube) will be forced to open offices in Turkey and be at the ready to shut down users, sites and content that the government deems offensive. If they do not comply in 48 hours they will be fined $700,000.

Along with Erdogan’s ruthless campaign to cement his power also comes an attempt to force the Turkish people to become better Muslims. In particular, Erdogan has emphasized Islamizing education. The government is pushing children into religious schools, known as Imam Hatip (“Imam and Preacher”). Detailed Constanze Letsch of the Guardian: “Under a scheme introduced by the government last year, about 40,000 pupils were forcibly enrolled in religious Imam Hatip schools, Turkish media reported. In some districts religious vocational schools were suddenly the only alternative for parents who could not afford to educate their children privately.” Many Turks are unhappy with such obvious indoctrination.

Reported Reuters: “Some secularist parents say the Islamist school movement is robbing their children of resources and opportunity.”

However, Erdogan’s attempt to build a new “pious generation” so far has failed badly. His increasingly repressive rule, including a campaign against followers of Muslim cleric Mohammed Fethullah Gulen, undermined his message. Moreover, government religious propaganda has proved especially unwelcome to many younger, involuntary recipients.

Explained the Guardian’s Bethan McKernan: “a study by Sakarya university and the ministry of education from earlier this year looking at religious curricula in Turkey’s school system found that students are ‘resisting compulsory religion lessons, the government’s “religious generation” project and the concept of religion altogether.’ Almost half of the teachers interviewed said their students were increasingly likely to describe themselves as atheists, deists or feminists, and challenge the interpretation of Islam being taught at school.”

Religious indoctrination is only the start, though Turkey is not the harshest Muslim country in how it treats its religious minorities. Akyol explained: “Regarding religious freedom, the scene is not that dark, but not very bright either.” Similar was the assessment of Andrew Brunson, the American pastor imprisoned for roughly two years by the Erdogan government: “There is still a high degree of freedom for Christians relative to other Muslim countries in the region, but I am concerned that all the signs point to this changing very soon.”

Open Doors ranked Turkey at 36 on its list of the 50 worst persecutors. In its latest report the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom explained: “In 2019, religious freedom conditions in Turkey remained worrisome, with the perpetuation of restrictive and intrusive governmental policies on religious practice and a marked increase in incidents of vandalism and societal violence against religious minorities. As in previous years, the government continued to unduly interfere in the internal affairs of religious communities.”

Moreover, reported the Commission:

Religious minorities in Turkey expressed concerns that governmental rhetoric and policies contributed to an increasingly hostile environment and implicitly encouraged acts of societal aggression and violence. Government officials and politicians continued to propagate expressions of anti-Semitism and hate speech, and no progress was made during the year to repeal Turkey’s blasphemy law or to provide an alternative to mandatory military service and permit conscientious objection. Many longstanding issues concerning religious sites, such as the inability of the Greek Orthodox community to train clergy at the Halki Seminary, remained unresolved.

The State Department made similar points in its annual report: “The government continued to limit the rights of non-Muslim religious minorities, especially those not recognized under the government’s interpretation of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, which includes only Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Christians, Jews, and Greek Orthodox Christians. Media outlets and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) reported an accelerated pace of entry bans and deportations of non-Turkish citizen leaders of Protestant congregations.”

One of the important disabilities suffered by Christians, especially Protestants, is the steady expulsion of foreign workers who possess long-term residency visas. They frequently help train local clergy. Some 50 families have been forced to leave in recent years, often without any explanation.

Unfortunately, warned Alexander Gorlach of the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs and Religion & International Studies Institute: “The problem is not just government. Hostility toward non-Muslims afflicts Turkish society.” Ramazan Kilinc of the University of Nebraska noted that: “conspiracy theories about non-Muslim minorities dominate the public sphere. At the root of these stories, Christians are depicted as collaborators with foreign powers to undermine the Turkish identity.” Christians suffer social and employment discrimination. Muslim converts often face great pressure from their families.

Popular antagonism increases the likelihood of more intense government persecution in the future. The AKP lost the Istanbul mayoralty last year, reflecting Erdogan’s declining popularity. He might seek to focus public wrath on religious minorities, especially with ties abroad. Worried Gorlach: “Step by step, using a nationalist and Islamic rhetoric, Turkey’s Christians are becoming a welcome scapegoat for Ankara.”

For instance, Brunson was arrested when Erdogan sought a hostage to trade for Gulen, who lives in Pennsylvania and was improbably blamed by Erdogan for the failed 2016 coup. Ankara held Brunson, an evangelical pastor who had lived in Turkey for 23 years, on a succession of increasingly fantastic charges (he was a Gulenist, coup plotter, U.S. spy, and more). Erdogan taunted Washington: “You have a pastor too. Give him to us.” Brunson was released after the U.S. imposed economic sanctions on Turkey.

The rise of radical Islam put Christianity at risk throughout the Middle East. Thankfully, Ankara does not yet pose the sort of existential threat demonstrated by the Islamic State and other jihadists.

However, Turks have been willing to use great violence in dealing with what they view as threats to their nation’s nature and unity. Both are thought by Erdogan and many of his countrymen to be threatened by Christians and other religious minorities. Moreover, the AKP may increase Islamification efforts, whether out of religious belief, political opportunism, or both. If so, religious minorities, and especially Christians, could find themselves in the regime’s crosshairs.

Warned Kilinc: “Turkey is an important country for the history of Christianity, yet the future of Christian presence in Turkey, I believe, is under threat.” The defense of religious liberty in Turkey will require ever greater vigilance in coming years.

Doug Bandow is a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.

Comments