Choose Your Enemies Wisely

You know the constant griping I hear from a certain kind of Christian conservative, concerning the Benedict Option: that it’s a call to retreat from the front lines of the culture war. They’re not exactly wrong. It is a call to disengage from the primary front, and to take up new forms of resistance, because under present conditions, we cannot hope to win in a conventional way.

I was thinking about this the other day when considering the case of Vaclav and Kamila Benda. Vaclav was a Czech anticommunist dissident who really was on the front lines — and who went to prison for his political labors. Kamila, his wife, was equally a dissident, but she did not put herself on the line in precisely the same way her husband did. Her resistance was quieter; it was one of nurturing the movement. She told me last year that when her husband had been suffering in prison for years, the government offered him amnesty in exchange for leaving Czechoslovakia with his family. He was tempted to take it, in part because he hated that his wife was having to raise their large family on her own in his absence. Kamila wrote to him to say no, stay there; we’re fine on the home front. If we take the easy way out, she said, what will that say about our cause? What kind of message will that send to the dissidents who don’t have the same opportunity?

So Vaclav Benda (d. 1999) stayed in prison, and Kamila Bendova remained at home, raising their children, doing her part for the resistance.

Vaclav Benda was a more conventional hero. We find it harder to appreciate the heroism of a Kamila Bendova — but that is exactly the kind of heroism we need as much if not more than the former.

I say this because a reader asked me to reply to this talk by an Estonian Catholic lawyer who calls for Catholic men to recover their militancy. He writes, in part:

In many ways, the battles we face today are more complicated than the military conflicts of the past. Every man knows what he is called to do when a hostile army invades his country. But what do when it is difficult even to understand the nature of the battles – inside the Church, and outside in the realm of philosophy, morals, culture, law, politics and the economy – let alone our role in them? It requires prayer, contemplation and doctrinal formation to understand the sly and insidious Revolution that does not show itself openly yet seeks to corrupt everything true, beautiful and good.

Our battles are predominantly spiritual. As Alexander Solzhenitsyn said, “the battle line between good and evil runs through the heart of every man.” This is where our most important battle is fought because it profits us nothing to win the whole world but lose our soul. We must bear in mind that when we fight the forces of evil we cannot succeed if we rely on our own strength. Our only hope is that God works in and through us. However, we must prepare ourselves properly to make this possible. If sin lives in us, we cannot fight sin outside us. This is why the sacraments, prayer and proper spiritual direction are so important.

There is a lot we can learn from the words of the Greek statesman, Demosthenes. When difficulties caused his fellow citizens to lose hope he told them: “Athenians! Certainly, things are going badly and you are in despair. But in this you are wrong! If, after having done all that was necessary to ensure that things should go well, you had still seen them turn out badly, you might have reason to despair. Yet hitherto things have gone badly only because you have not done what was necessary so that they should do otherwise. It is still open to you to do what you have so far not done. Then things will go well. Why, then, should you despair so soon?” Let us bear these words in mind and think about what we can do, firstly to understand the battle, secondly, to prepare ourselves for it, and finally, to engage in fighting for the values, principles and ideals that form our Catholic faith.

We are told by the modern world that the problem with society is excessive masculinity. Nothing could be further from the truth. The meaning of masculinity has been distorted and it is our task to restore it – first of all in ourselves and then in society at large. This restoration begins in the understanding that masculinity is about militancy in the broadest sense. Men, by their nature, are called to be defenders of truth, justice, goodness and other high ideals. To fight against the enemies of the Church in the spirit of love, dedication, perseverance and sacrifice is a vocation we are called to for the greater glory of God, for the salvation of souls and for the sanctification of our own soul. This fight must begin in our soul but it extends to every aspect of our spiritual and social life, with kindness and love, but without sentimentalism, false piety and softness. If we are to be the light of the world we must let the light of God shine, without fear or compromise, without counting the cost, trusting in God and relying on His grace. Fighting goes hand in hand with sacrifice and suffering and this provides us with a simple, but effective test: if we do not suffer, then we are not fighting any serious battles.

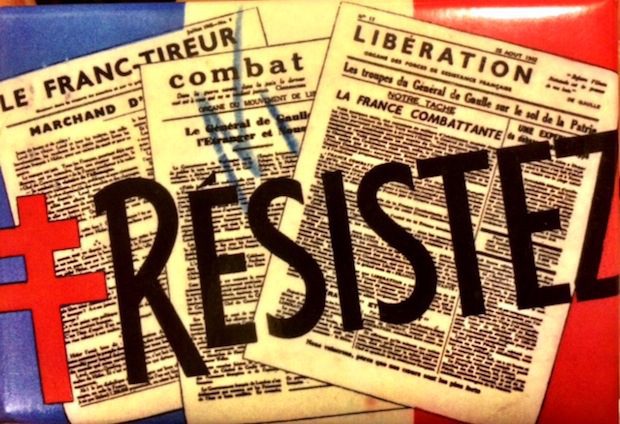

I agree with this, and I’m not sure at all that the writer, a man named Varro Vooglaid, would disagree with the Benedict Option. The battle we face really is more complicated than in the past! And that’s why the heroes we need are fit for the battle we face now, not the one we faced 50 years ago. Tactics the French army learned for the conventional battlefield were only of limited use to the French Resistance.

I think of these white nationalist armchair soldiers who express concern with the unwinding of Western civilization, but who don’t do anything about it except nurture violent grievance fantasies and, on occasion, act them out. Do they marry? Do they have children? Do they start or help build up schools where children are taught about Western civilization? Are they part of a church? And so forth. If not, why not? Is it because doing the dutiful things necessary to build and to hold something of worth seems too boring?

To switch the metaphor: for traditional Christians, this crisis is not the 100-meter dash; this is a marathon. We are going to have to find a way to revive the militant spirit of which Vooglaid speaks, but also to channel it in prudent ways appropriate to the nature of the war we fight.

What I’m hearing from my traditional Christian contacts around the country is frustration over the unwillingness of people who think of themselves as religious conservatives to do the hard work of building and sustaining a real resistance. One man told me not long ago that he and his wife took their kids out of their local Catholic school and put them into a classical Christian school because their kids weren’t learning anything at the Catholic school. He said that he and his wife finally concluded that most parents didn’t want the Catholic school to be challenging, not on faith matters or anything else.

I heard the same thing last year from a Catholic educator who told me that the Catholic school bureaucracy in his city was mediocre and fiercely devoted to protecting that mediocrity. And most parents, in his view, were happy with that, because they were only really interested in alleviating their anxiety over their children’s education. That is, they wanted to be able to tell themselves that their children were getting a “Catholic education,” whatever that turned out to be. This, in a deep Red State diocese.

As an Evangelical educator told me once, “A lot of people who send their kids to classical Christian schools are really only concerned with saving their kids from liberalism.”

In his talk, Vooglaid identified three battles as having been crucial for the survival of Christendom: Tours, Lepanto, and Vienna 1683. He’s right about that, but notice that all three of those battles were literal battles, and were against an outside enemy (forces loyal to Islam). Today, the battle is within. Vooglaid says:

The militant spirit and the virtue of militancy cannot merely be intellectual they must also be practical – that is, about our own lives. It is wrong to fall into the error of activism, seeing action as the sole means of our fight, it is just as wrong to adopt pietism or intellectualism, refusing to engage in action and hoping that prayer or endless discussions will solve our problems.

He’s completely right here as well. To this I would add, again, that militancy is not an either-or question. Yes, we have to fight for religious liberty, and for other things we hold to be true and good. But as Christians, none of it matters if we fail to pass on the living faith to our children.

Here’s an example, though not about religion in particular. It has helped me think more clearly about my next book project (of which I expect to have good news to report soon). As I was struggling with the nature of the project, and whether or not to focus on recrudescent socialism, a friend put a couple of questions to me. Basically, she said:

If we kept electing Republicans from here until kingdom come, would that change the threat you see?

If we kept the economic status quo, would that change the threat you see?

The answer to both questions is: No.

That being the case, then the problem is not really socialism, is it?

In the same way, if traditional Christians can’t identify specific, achievable goals that would enable them to say, “We have won this war,” then we had better reconsider how we fight it.

True, the battle is never truly winnable until the end of time. We know this. At this point in our time and place, “winning” is not even converting the world; it’s simply holding our own. We should want to convert the world, but right here, right now, it is more important to convert ourselves and our children. Or, as the church historian Robert Louis Wilken put it back in 2004:

Nothing is more needful today than the survival of Christian culture, because in recent generations this culture has become dangerously thin. At this moment in the Church’s history in this country (and in the West more generally) it is less urgent to convince the alternative culture in which we live of the truth of Christ than it is for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life, the culture of the city of God, the Christian republic. This is not going to happen without a rebirth of moral and spiritual discipline and a resolute effort on the part of Christians to comprehend and to defend the remnants of Christian culture.

Fighting for the independence and liberty of Christian schools is extremely important. But if those schools don’t use their liberty and independence to form intellectually, morally, and spiritually serious Christians — as opposed to good middle-class American achievers with a veneer of Christianity — it will all have been in vain.

Philip Rieff said:

The death of a culture begins when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals in ways that remain inwardly compelling, first of all to the cultural elites themselves.

The greatest challenge facing believing Christians today is to communicate the faith and its teachings in way that remain inwardly compelling to ourselves and our children.

Not outwardly compelling, but inwardly. Vooglaid is right: we do need militancy, but rightly targeted. Francoist Spain was thoroughly, formally Catholic. And when Franco died, so did a large part of the Church there. Similarly with Ireland, where the Catholic Church was formally dominant, but which had ceased to be able to convey its ideals to its people in ways that were inwardly compelling. This is why Irish Catholicism collapsed so quickly.

So it will be with the rest of us. Choose your enemies wisely.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.