No Sympathy For The Devil

I feel the need to explain to you why I am so alarmed by what Trump is doing this week, and more than that, by what is happening in our culture. For you who have read my books, or read this blog for a while, most of this will be old news. I beg your pardon, then, for repeating myself. But this stuff is all personal to me, for reasons I’m about to explain.

What worries me most about Trump and the Trump mob is the fear they give me for dissenters. Most of my adult life, in every institution I’ve been a part of — schools, media organizations, church), I have been a dissenter of some sort. It’s partly my nature, but the fact is, I have found myself in the minority in a crowd. Not a mob, but a crowd. A mob is an angry crowd that has lost its reason. Crowds turn into mobs easily, even if they aren’t aware of it. I have seen polite, professional mobs at work. These are the mobs who hide their mobbishness from themselves. More on which in a second.

If I had to pick one single event that formed my outlook on the world, it would be a couple of minutes on the floor of a hotel room at the beach, in the summer of 1982. I was part of a group of high school kids from our town who were on a summer vacation. We were chaperoned by several parents of kids on the trip. The cool kids had been pushing me and a couple of other kids around the whole time, but it was relatively minor stuff. One afternoon, when a bunch of us kids gathered in one of the hotels’ suites, group of older high school boys threw me onto the ground, pinned me, and tried to pull down my pants. The goals was to humiliate me for the amusement of the high school girls in the room.

I was 14. And I was terrified.

They had been picking on me for days, but this was a real escalation. What made it so important to the development of my worldview was that I was lying on the floor, pinned and helpless as I struggled to get free, I called out to the two adults in the room to help me. Both of them literally stepped over me to get out of the room. As I’m sitting here writing this, nearly four decades later, I can recall with crystal clarity the stitching on the pants leg of the jeans one of those moms wore as she stepped over me (the other mom went around me).

After a minute or so more, the boys let me up, and I ran away. They never took my pants down; they were just toying with me. For all I know, as the two moms left the room, they signaled to the boys to knock it off. The point is, though, that rather than use the authority they had to force this idiot small mob of boys, and the girls who stood on the hotel room beds jumping up and down, squealing and egging them on, to stand down, they walked away. No doubt because they wanted to stay in good with the cool kids. These were the kind of moms who wanted to be friends with their teenagers, not authorities.

Here’s something else: this was not an angry mob (and not much of a mob either: maybe seven or eight boys, and that many girls). They were merry. I was a mouse, and they were cats. They were doing something vicious, but to them, they were just having fun. There was no point to what they did other than to amuse themselves by the suffering of someone who couldn’t fight back.

The whole thing might have lasted two minutes at most. But the shock waves of that have reverberated throughout my life. I learned more in those two minutes about the way the world really works than I have learned in five decades, though it took a very long time for me to understand that.

After I returned home from that summer vacation, I wanted to get out of my hometown. This mob kept it up, tormenting me and others, until I finally moved away for good, at the start of my 11th grade year. Anybody who has had to suffer at the hands of the cool kids in high school knows what this is like.

I can say that I am not a Catholic today because of what happened in that hotel room. As you probably know, I lost my Catholic beliefs around 2005, and formally left the Catholic Church in 2006, after having been shattered by covering the sex abuse scandal. I remember the two moments, early in my coverage, that touched the rawest nerve. The first was talking on the phone in early 2002, shortly after Boston broke, to Horace Patterson, a Kansas farmer whose son Eric committed suicide a few years after having been molested by a priest. It turned out that there were five suicides of that priest’s victims. The Catholic Diocese of Wichita knew what Father Larson was, and kept reassigning him. I sat in my office in New York City talking by phone with Horace, and listening to him tell me about what their family had been through, and heard the story about how he sat on the front porch of his farmhouse after he received the phone call that Eric, his beloved son, had blown his brains out. Horace sat there waiting for his wife, Eric’s mother, to come home. He saw her turn in at the end of the long road, and motor towards the worst moment of her life.

I heard that, and thought about my own little Catholic boy back home in Brooklyn. These bishops, these sons of bitches, would have allowed the same thing to happen to him, if we had been in the Pattersons’ position.

The second time the scandal touched the nerve was reading court filings in a particular abuse case. I can’t remember which one it was, but one priest testified that he had walked into a bedroom at the rectory, caught Father so and so having sex with an altar boy, and shut the door on them to give them privacy.

That priest was a mob. The Catholic bishops were a mob. They metaphorically walked over the bodies of innocent victims — the molested kids and their families — to get out of the room, so to speak. Maybe they just wanted to avoid trouble. Who knows? The point is, this is what those cowards did, over and over and over.

The day finally came when I could no longer believe as a Catholic. It’s not that I decided not to believe. I just couldn’t believe in it anymore. The rage at the injustice, including the systematic lying by the bishops, and the unwillingness of most of the laity to see what was right in front of them, and demand change — it was an acid bath that corroded everything within me tying me to Catholicism. This is something that is hard for many Catholics to understand. They keep saying that the sins of the clergy don’t negate the truths of the Catholic faith — as if that has anything to do with the psychological reaction inside people. The sins of an abusive parent don’t negate the biological and legal reality of their parenthood, but they can drive a child into permanent exile from that family, if only to feel safe.

I had to learn from the experience of losing my Catholic faith how to handle the rage that comes from watching authorities walk away as the vulnerable are bullied. The greatest tension within me is my hatred for authority, based on what I have observed, and at the same time recognizing the legitimacy of authority, and the necessity of it for the building and maintenance of a civilized order. Without authority, we are left with mob rule. But an authority that permits mob rule is no authority at all.

There’s a lot more to this for me. My late father was the embodiment of Justice for me. He really was in most respects a just man, and a man who insisted, angrily, on justice. And he was right to! In his first job, he was a state health inspector. In my childhood, I overheard him tell my mom once about an official who tried to bribe him to let the facility the official oversaw pass a health inspection. My father was outraged that the official thought of him as the kind of man who could be bribed. I was so proud of my dad, and his honor. He was in most respects not only a good man, but a very good man. When he lived, he had a deserved reputation for being a man of wisdom and justice.

But his greatest flaw, the flaw that has had a devastating impact on our family system, was that he never, ever considered that he might be wrong about anything. I didn’t see this until I became a teenager, and didn’t see how far this error would extend until I returned to Louisiana in 2011, and came to realize that my father would sooner see everything around him fall apart than admit that his judgment about me, and things related to me, had been mistaken. Justice without mercy becomes tyranny. And mercy is only possible when one is humble enough to recognize one’s faults, and how much one depends on the mercy of others when one fails.

Of course I couldn’t see that as a small boy. For me, Daddy was justice. This is why I hero-worshiped him as a boy. He was strong, but also gentle. In most respects, he really was a model of how to exercise authority with compassion — so much so that when I disappointed him, I assumed that I was in the wrong.

It was only when I became a teenager, and began to defy him — in truly minor ways, like wanting to wear my hair a certain way — that I began to see his tyrannical side. He wanted to impose control on me, and didn’t care what in me he had to break to do it. He alienated me — drove me away — rather than admit that maybe he was too harsh (and believe me, this is a lesson that I have taken to heart in the raising of my children). Truth to tell, when I went off to public boarding school at 16, I was mostly running away from the kids in my school, but I was also running away from my father, who once suggested to me that the reason I was being picked on was because I was so weird.

In my history classes in college, I had to confront the fact that during the 1960s, when the Civil Rights struggle was going on, most of the older people — white people — I had grown up admiring were on the wrong side. By then, I didn’t talk about race with my dad. I was a semi-militant liberal as a college student, and I’m sure I was insufferably self-righteous. I think of the final argument we had about race and history. His basic belief was that the hearts of his generation had been in the right place, and yes, maybe Mistakes Were Made, but they only wanted to preserve order. When I challenged him on this, he became infuriated, and accused me of disrespecting him.

“I’m your father!” he raged that night. “Do you think I’m lying to you?!”

I told him that it wasn’t a matter of lying, that it was a matter of interpreting the facts — and that my conclusion about the facts was different from his. I have never seen him so angry. My father never hit me, but I think that night in the 1980s, he wanted to. Like I said, he simply could not imagine that he was wrong about anything.

Keep in mind what I said about my father having been the embodiment of Justice for me as a small boy. I was unlearning that. We quit talking about race and history after that night, because it was clear that we couldn’t do it. As I came to understand over the years, in the Jim Crow era, my dad and white people of his generation really did believe that maintaining a just public order required treating black people — the poorest of the poor in our part of the world — as second-class citizens.

Some of them believed in employing extrajudicial violence to maintain that order. As an adult learning more about the history of my place, having to come to terms with the fact that many of the older men I grew up being taught to respect had in fact been Klansmen, forced a terrible reckoning. I only learned the names of a few of them, though there had been many more. These were names of men who were pillars of the community. It would have been easier for me had these men been nothing but monsters. In fact, they were men like my father — ordinary people who were in many cases kind, funny, and loyal. Even kind to blacks. I have seen this with my own eyes. Human beings are strange. I wish I had been able to talk at length with my father, in our later years together, about those times, and why the people back then thought the way they thought, and how they reconciled it with what they professed to believe about righteousness. But it wasn’t possible.

I did get this story from my father back then, who heard it from one of the men who participated in it. Back in the 1940s, the sheriff of West Feliciana Parish, a man named Teddy Martin, put out a call for help. A black man had been caught raping a white woman, and fled into the woods. The sheriff needed some strong men to help him track the rapist. The man who told the story to my dad was one of the posse (there was only one other, beside the sheriff). They caught the black man, carried him back to the town jail, and lynched him that night.

Two days later, the white woman who had been the rape victim broke down and confessed that she and the black man had been lovers. She accused him of rape when they had been caught having sex. Her conscience was consuming her, and she broke.

Nothing happened to these murderers, the sheriff and these two working-class men (I know their names — they’re both long dead). The white woman and her family moved away, to escape the shame. The old man who told my father this story thirty years ago or so was nearing death, and must have related it to my dad to clear his conscience.

My dad told me that story back in the 1990s, on one of my visits home. The old man who confessed to him had recently died, and the confession came up as my dad and I were talking about the fellow. My dad was clearly jarred by what the old man had told him. I recall trying to talk to my dad about how that confession might have caused him to rethink any of that. I was still young back then, and was under the impression that most people wanted to know the truth, and wanted to search their own consciences, and to live in truth. Daddy had no idea what I was talking about. He really didn’t. He saw no connection. This was just an unfortunate thing that had happened. But Mr. ____ was a murderer, and he got away with it! I thought.

I remembered, though, the lesson of fighting with my father about all this when I was in college. Daddy didn’t want to hear anything at all that contradicted his worldview. Mr. ____ had been a just man and a good neighbor. That thing he had done in the past — well, that was the past. Mistakes were made. Mr. ____ was a good man. Good men don’t murder innocent men. Therefore, somehow, what happened at the jailhouse that night must have been forgivable. A just world was a harmonious world, and if maintaining that harmony required a mob behaving unjustly at times, well, the greater justice made it worthwhile, didn’t it? Said Caiaphas, the high priest, “You do not realize that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish.” (John 11:50)

Earlier this year, in my travels, I spoke to an older Catholic who has lived a life of distinguished service to the Church. This person told me that it has been extraordinarily painful to be faced, in the twilight of years, with evidence that the institution to which so much service has been given was in many cases unjust and corrupt. My Catholic interlocutor, whose name many of you would know, had undertaken an excruciating self-reflection. Most of us don’t have this capacity, or doubt that we do. Reflecting later on my conversation with the older Catholic, I recalled that my late father could not allow himself to think the kinds of thoughts that this Catholic layperson was thinking. He was afraid that his entire world would fall apart. Thus, Caiaphas.

We are all like that to some extent, aren’t we? Let me say clearly and unambiguously here: I recognize that if I had been born into my parents’ generation of whites — born in the 1930s and 1940s — in that same place, I would have almost certainly have held the same views as all other whites back then. In those days, before mass media made it possible to conceive of competing narratives, it would have required extraordinary consciousness for whites to have given a fair hearing in their minds to a rival narrative, and almost unimaginable courage to have resisted the received narrative by which everybody you knew and loved understood the world. When every institution around you, and every moral authority around you, upholds white supremacy as the Way The World Is, how are you going to find the grounds to resist it?

If you, white reader, think that you would have been the brave resister, I believe you are lying to yourself. I would love to think that I would have stood up for what was right, and damn the consequences. I am sure that I would not have done this, and more to the point, I am sure that it would not even have occurred to me to do this.

Read this article from Ebony magazine, in 1964. It’s about the day in 1963 when a black man, the Rev. Joseph Carter, went to the courthouse in my hometown to register to vote, as was his right. He was confronted by the local sheriff and white officials who were determined to stop him. He was also confronted by a howling white mob, aflame with hatred. I didn’t discover this article until 2012. I had no idea this had happened in my town. It was a hell of a thing to realize that I probably knew the names of most of those whites in that mob. I certainly knew the name of the sheriff, who died a few years back, and the name of the registrar of voters, who was a dear friend of my late grandfather.

It was also a hell of a thing to realize that if I had been a man in his 30s or 40s back then, I might have joined that mob. Or, more likely, I would not have joined it, but would not have stood up to it either. When the Church tells us that every one of us would have been in that mob in Jerusalem, demanding the crucifixion of that innocent man, Jesus, pay attention. At best we would have been like Peter, hiding out from the mob, and denying that we even knew the condemned man.

This is not a white thing. If you, black, Hispanic, or Asian reader, or gay reader, or religious minority reader, think you and your people are not capable of this kind of thing, under the right circumstances, turn from that self-deception right now. Evil does not reside in this race, but not in that race. This is the human race. In the natural course of things, he who is bullied today will bully tomorrow, when he has power.

So look, I hate the mob, and one thing I hate most intensely about the mob is the sense of innocence that it grants to itself. It has been my fate to work in a number of professional milieux in which I am a political, religious, and cultural minority. I have witnessed over and over again how the mob mentality works in those settings. It is genteel, usually, and cloaks its tyrannical qualities from itself in the language of therapy and social justice. But it is a mob, and it is led by people who are infinitely more sophisticated, intelligent, and polite than Donald Trump. They have no problem crushing the weak in the name of social justice. They don’t even think about it — in the same way the Catholic bishops didn’t think about it, and the ruling class of West Feliciana in the 1960s didn’t think about it.

Antifa is the left-wing mob par excellence. But the mob mentality doesn’t require taking to the streets with rocks in your hand. The progressive mob that wants to smash a Baptist florist and an Evangelical wedding cake maker in the name of justice — that’s a mob. The progressive mob that demonizes dissenters in corporations, and colleges, and on the pages of our leading newspapers, smearing them as evil people who need to be silenced and made to suffer for their thought crimes — those are mobs. I have been present when right-thinking liberals, reinforcing each other’s righteousness, have spoken with shocking contempt of those who oppose their views. When you read on this blog me talking about fearing the contemporary left in power, it comes from having observed them up close, and having listened to them. So many of them genuinely believe in their own righteousness, and would no more question their judgment than my father questioned his, or the Catholic bishops questioned theirs.

But they can’t see this, because they believe, contra Solzhenitsyn, that the line between good and evil runs between themselves and other men. In his great work Crowds And Power, Elias Canetti writes, “A murder shared with many others, which is not only safe and permitted, but indeed recommended, is irresistible to the great majority of men.”

There is no such thing as perfect justice in this world. When there is a conflict, someone has to lose. This is inevitable. Justice is not therapy. For example, Central Americans are fleeing misery, but that does not mean they have a right to settle here without the consent of the people who already live here. Justice cannot be determined solely by whether or not the people we prefer prevail. One frightening thing about progressives today is that so many of them have given themselves over to the Marxist-Leninist view that justice is what distributes power to particular classes. The twentieth century is filled with warnings about where that mentality leads. It must be admitted, though, that though you would not have found a single Marxist-Leninist, or even a progressive, in power in the Jim Crow South, those committed to white supremacy also saw justice as defined by what distributed power to themselves. They just weren’t as honest about it as our progressives today are.

We shouldn’t deceive ourselves about this. Only God gives perfect justice. Here in the mortal realm, if we are good, then we strive to do the best that we can, recognizing at all times that our verdicts cannot help falling short of perfection. Still, we have to judge. If we are going to judge rightly, then we have to judge as dispassionately as we can. Wisdom is not something that an algorithm can produce; a wise judge uses his head, but does not ignore the counsel of his heart. Yet if we are going to have the rule of law, then we first must establish the rule of reason over the passions. Without this, civilization isn’t possible.

In 2002, a teenager in Baltimore shot in the leg a Catholic priest who had molested him years earlier. I remember reading about this at the time, and thinking, “Good! That priest deserved it.” I had to repent of that thought. Whether or not the priest deserved to be shot in the leg is beside the point. We cannot allow ourselves to choose to live in a world in which men are shot on the street, even for crimes they committed. To have approved of that act, even in the chambers of my heart, is to sanction the mob. As I said, I repented. Believe me when I tell you that not a week goes by in which I don’t have to repent of something like this. The struggle with the righteous mob within is the task of a lifetime.

As I’ve said, I do believe that the mob mentality rules in many of our institutions heavily dominated by progressives. The hide their mobbishness from themselves behind cloaks of righteousness. Their victims are legion. A recent one: Dr. Allan Josephson, a distinguished psychiatrist who spoke out publicly about his doubts, as a medical professional, about transgender treatment. He was driven out of his institution. We could go on all day about people like this — people crushed by the progressive mob for holding the “wrong” views. What progressives don’t understand is that a creature like Donald Trump is, to a serious degree, a response to their own mobbishness.

What makes a mob a mob is the degree to which it surrenders reason, and acts based only on emotion. It’s easy to know that you’re looking at a mob when you see Antifa mass on the streets of Portland. It’s easy to spot a mob on social media, when the Twitter legions smash and grab. It is more difficult to recognize that you’re looking at a mob when the faculty masses behind the scenes to punish crimethinkers, who deserve no mercy or consideration.

But.

The Trump mob, convinced of its own righteousness, doesn’t recognize what it is turning into. They’re willing to run over dissenters, even bad people like Ilhan Omar, to get what they want — and just like the progressives they loathe, they’re hiding from themselves what they’re doing. I’m so tired of hearing that whatever Trump says or does is justified, because progressives are so wicked that they must be stopped by any means necessary, and if you object to that, then you must be some sort of cuck. Really? Was Tolkien a cuck when he warned, in one of the greatest literary works of the blood-soaked 20th century, that seizing the Ring to defeat evil was going to corrupt? Was Solzhenitsyn a cuck when he recognized that the fathomless evil to which he bore witness could be reproduced anywhere on this earth, because the line between good and evil bisects the heart of every one of us?

There is a meaningful difference, I believe, between the mob mentality exercised within institutions, and the actual mob gathered on the street. The mob on the street is subject in a particular way to the demonic. Let me explain what I mean.

I said in a post yesterday that Trump is summoning demons. This is a phrase I have also used a number of times in the past to describe what progressives are doing with their rhetoric on racial matters, and other things. I use the concept of the demonic in both a metaphorical and a literal sense.

Metaphorically, I mean that these political figures are calling up extremely dark passions that history shows can easily master individuals and peoples. A few days ago, I was standing in a gas chamber at Auschwitz. I will never understand how any human society can build such places, much less what was the most technologically and culturally advanced society on earth at the time. We don’t have to understand it to recognize that it happened, and that if it happened once, to intelligent and cultured people, it could happen again. The demons that Germany gave itself over to could come calling for us as well. And also the demons that Soviet Russia invited in. And Red China. And, for that matter, the slave-owning South, and the Jim Crow South.

Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and their demons, and the demons of their followers — that’s far away. But think of the demon that drove the old man in my town who was a friend of my father’s to trust authority — the sheriff — and to trust his culture’s narrative, and to participate in the lynching of an innocent man one night, because the man had to be guilty, according to that murderer’s understanding of the world. No white woman would voluntarily have sexual congress with a black man. That black man had violated the purity of that white woman, and in so doing had attacked the foundation of Southern society. He was no human at all, in fact — he had to pay to restore order to the world.

Had the black man been brought to trial, there was a chance, however slim, that the demon’s lie would have been exposed under rational deliberation. That the lie of the supposed victim would have come out. That the black man would have been set free. But the mob — the sheriff and his two helpers — they knew the truth in their hearts. They executed justice by executing the black man without trial. They didn’t think they were surrendering to a demon. They surely thought they were agents of righteousness. I have no idea if any of those three murderers were churchgoing men, but certainly they would have considered themselves Christian. But they gave themselves over to a demonic (dark, overwhelming, irrational) passion for what they thought was justice — and became killers.

There is also this. Tony Judt wrote, in remembrance of the Polish thinker Leszek Kolakowski, about the one time he heard the great man lecture:

The seductively suggestive title of Kolakowski talk was ‘The Devil in History.’ For a while there was silence as students, faculty, and visitors listened intently. Kołakowski’s writings were well known to many of those present and his penchant for irony and close reasoning was familiar. But even so, the audience was clearly having trouble following his argument. Try as they would, they could not decode the metaphor. An air of bewildered mystification started to fall across the auditorium. And then, about a third of the way through, my neighbor — Timothy Garton Ash — leaned across. ‘I’ve got it,’ he whispered. ‘He really is talking about the Devil.’ And so he was.

Kolakowski had survived the Nazi occupation of Poland and the de facto Soviet occupation. I’ve been reading him lately, and thought it’s not clear if he ever became a religious believer, he was certainly acquainted with the devil — and he did not believe in the devil as a mere metaphor. I also believe in the demonic as a real force. I have been worshiping as an Eastern Orthodox Christian for 13 years. Orthodoxy tells us that the life of each individual Christian is a constant struggle to master the inner passions, and against the demons. I believe in demons — real demons, meaning discarnate intelligences that are malevolent and chaotic, and that serve death.

Many of those drawn to Donald Trump are Christians — Christians who correctly see that the forces aligning among progressives against us really do hate us, and wish to see harm done to us. Personally, I have no time at all for progressives who tell themselves that social and religious conservatives are nothing but paranoids. We see what you have done, what you are doing, and what you will do if you are not stopped. We see this even if, blinded by self-righteousness, you don’t. These Christians — on some days I am among them — are drawn to Trump not out of any respect or affection for him, but solely out of self-protection. It would be a near-miracle if progressives who are mystified by Trump’s popularity would ask themselves, in all honesty, if they have given conservatives reason to fear them such that they (conservatives) would see a manifestly bad man like Trump as the lesser evil.

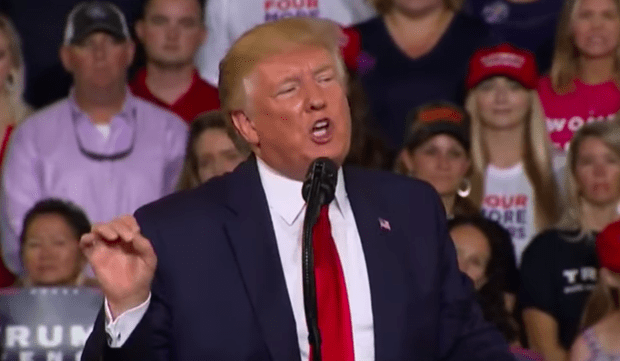

That said, when I look at Trump’s crowds, shouting, “Send her back!” about Ilhan Omar, I instinctively take the side of the dissenter. From what I know of her, Omar is an appalling figure, and I hope everything she touches in politics fails. But I know the demonic when I see it, and a US president stoking a crowd to chant that kind of thing about an American citizen is demonic.

Compare that to this short clip of the new Pope John Paul II on his first pilgrimage back to Poland after his election:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-oXXc5CfNw]

After having heard the pontiff’s preaching, the vast throng broke into a Polish hymn titled, “We Want God.” When I was in Poland last week interviewing people who lived through the communist era, several of them told me that this 1979 papal pilgrimage was the turning point in the life of the nation. Coming out to these masses was the moment they collectively realized that they were not alone. John Paul could have turned that crowd into a mob that tore Poland apart. He did not. He used his authority to make them a communion.

I might be wrong about this, but I seem to recall having read that Czech dissident leader Vaclav Havel, addressing a vast crowd in Prague’s Wenceslas Square during the Velvet Revolution, urged them not to seek revenge on their communist oppressors. He said something to the effect, “We are not like them.”

Havel was not a religious man, but he was doing what John Paul did: made a crowd that could easily have become mob into a communion.

Wojtyla and Havel spoke to the better angels of men’s natures. Donald Trump speaks to what is demonic. It doesn’t matter whether or not Trump’s targets are right or wrong. Wojtyla’s and Havel’s targets were not only wrong, but actually evil. Still, neither man resorted the demonic to fight the demonic.

To my Christian readers, I say this: when you watch Trump work those crowds, do you see the spirit of Havel, do you see the spirit of Wojtyla — or do you see something else? I saw that “something else” in Washington, at the big progressive pussyhat march. I saw it in the mob action against Judge Kavanaugh, and in the mob that attacked the Covington Catholic boys. The examples are endless. The weaponization of rage.

But it’s not just them! A mob that is on the side of justice is no less a mob. I have felt that rage too, and it’s intoxicating. If I had ever in my life been in a position to feel that rage standing shoulder to shoulder with others who felt that rage, and someone we trusted had told us to give in to it, to allow its power to run through our bones and our muscles, and to go forth and take power to work justice on those who hate us — it’s terrifying to contemplate.

This is what it means to surrender to the demonic, to the forces of destruction and vengeance and chaos. Very few people choose to do evil, knowing that it’s evil. We tell ourselves that it’s good. We tell ourselves that as good people, we could not do evil, therefore we find reasons to excuse ourselves, e.g., “Racism is a function of power, so I can’t be racist,” or “At least Trump fights, not like those gutless Republicans.”

“Evil is continuous throughout human experience,” wrote Kolakowski. “The point is not how to make one immune to it, but under what conditions one may identify and restrain the devil.”

This is our task: to identify and restrain the devil. We cannot restrain the devil by using the power of demons. It will consume us too. We will become like those we hate. This is an old lesson, and one that progressives who fight Trump should wake up and take seriously as well.

I told you at the start of this long, rambling reflection that yesterday’s Trump rhetoric struck me personally. I hope I have explained why, and explained why even though I fear and loathe the progressive mob, that can never justify taking the side of its conservative analogue. I’ve spent the summer reading about what communist mobs did. I spent Sunday looking at what the Nazi mobs did. A mob is what happens when we allow demons to possess the body politic, and cease to see human beings, and human dignity, except through the fevered eyes of our passions.

St. Paul told the Church in Ephesus that “our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms.” He meant that all warfare is ultimately spiritual warfare. We Christians need to be taking this more seriously than we do. And we need to stand with the targets of the mob, the dissenters, and protect them even though we may despise what they stand for. The mob is fickle. The life we protect today may be our own tomorrow.

Our nation is headed down a dark road, and I don’t have a lot of faith that we have within us the capacity to turn back. I hope I’m wrong. The mobs are going to do what they are going to do, but don’t let’s you and me try to stop them, and if we can’t, at least let’s not be in their midst.

UPDATE: Today the president said that he didn’t like the “Send her back” chants.

I’m sure that means he will take a lot more care with the way he uses rhetoric, then. So all is well. Right?

UPDATE.2: From reader J Lo:

Thank you Rod for writing this article.

I agree with you on so many counts (not perhaps the literal demon part) and it is interesting because I am an socially liberal 30-something born and bred in NYC, child of immigrant parents, agnostic and generally suspicious of religion and of Christianity in particular. We do not come from the same background, and if one followed political tropes, we should be on opposite sides.

My father grew up in Communist China, and in what was then rural village. In another life, he probably would have become an engineer, or perhaps an architect or an industrial designer. He had designed and directed the construction of a small bridge crossing one of the waterways around his village by the time he finished elementary school. Apparently, some passing political bureaucrat heard that and as a reward, had him come ride in the posh car going through he village. Somewhere along the way, it came up that my father came from a landlord family, and he was promptly asked to get out. I remember my father commenting how he had wanted to continue going to school, but that stopped after the primary school level because of his anti-revolutionary landlord family background (spots should be reserved for children from a good farmer/proletariat stock). There was a lot relentless government sanctioned bullying that went on back them, and people who did not have enough revolutionary “cred” or worse, was at the wrong end of the revolutionary spectrum suffered at the hands of their community, neighbors, even their own family. There were many who were tormented particularly ruthlessly, perhaps by their own righteous children, that ended up committing suicide. That was the mob mentality of the Cultural Revolution back then.

Today, what most reminds me of these stories of old, and what makes me most concerned is the blatant dismissal and blind vilification of the “other” in politics. The blind defense of even Trump’s most objectively idiotic blunders, to the point where anything disagreeing can just be casually labeled “actors and fake news” and dismissed, infuriates me. While the self-righteousness of the most strident far-left liberal strains feel that their views require no defense, that if you do not automatically agree it is because you are ignorant, bigoted, or “suck corporate d*ck”. People no longer feel the need to engage disagreement, because people who disagree have no value and do not need to be accorded the same consideration or even perhaps rights as people who agree with you (why else would someone say that an American citizen who has committed no crime could or should be forcefully ejected from the country, as if they had no rights? How “American” is that?).

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.