Fundamentalism & the Benedict Option

A reader sent a thoughtful letter about the Benedict Option. The reader agreed to let me publish it so long as I took out certain identifying details, which I was happy to do:

I’m hopeful for the possibilities of the Benedict Option conceptually but fearful about implementation, so I thought I’d share a bit of my story with you.

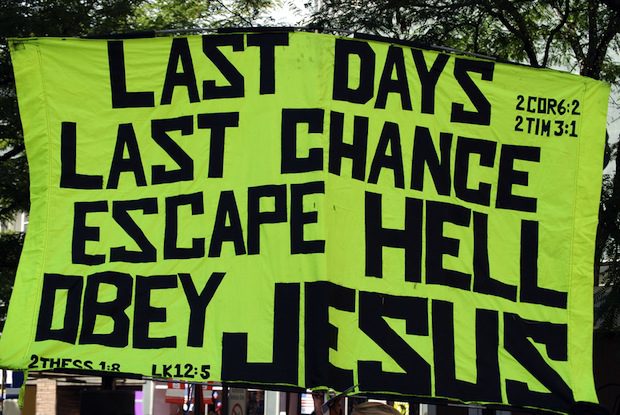

There are bleak possibilities of a Benedict Option gone wrong. I grew up in a fundamentalist church and converted to Catholicism during college. You’ve mentioned meeting people who were burned by fundamentalism, so let me add myself to the chorus of wounded people. I arrived in adulthood with little understanding of why orthodox Christian doctrine is important or what its existential significance is. I knew about the lines we were supposed to toe in order to avoid expulsion, but little about hope. It has taken me years to start getting over some of the traumatic abuses of authority that I witnessed in the fundamentalist environment, particularly as it related to my femininity. To this day I am less trusting of Evangelical men than non-Christian men because of the morally skewed vision of gender roles I expect they were indoctrinated with. Keeping young women in line was necessary to keeping the community together, and this sometimes meant the authorities turning a blind eye to the physical abuse of wives and children within the community. The whole experience left me rather tattered. Authority issues are certain to be serious for any community that clings to its own life.

The idea of Christian community is also potentially threatening to me because I am bisexual. For a while, after I had become Catholic, I rejected what I had heard in Evangelicalism about homosexuality and had a girlfriend. Through a couple years of studying, I’ve come to the conclusion that there exists a traditional Christian stance on homosexuality that is not just bigotry or social engineering, but I certainly never had any prior idea of the metaphysical significance of gender within Christianity because the Evangelical ‘stance’ on homosexuality was nothing but a political signifier in a community that existed only for its own self-preservation. I’m still in a quandary about how I should live my life, but having learned about the body of traditional Christian teaching on sexuality, I certainly think it raises metaphysically and morally substantial issues, which I didn’t before.

I strongly urge you to consider how a Benedict Option would deal with children who are unable to adopt conventional norms. In communities with rigid norms, it can be difficult for gays or any other ‘different’ person to even truthfully acknowledge their own inner experiences (prior to any behavior). This creates a barrier between the individual, God and other people. I’ve seen other people who were raised similarly to me utterly reject Christianity or become outspoken anti-patriarchal activists of the SJW ilk. I reject this kind of activism as spiritually detrimental, but it’s tempting when one has had legitimate grievances.

I’ve also seen BenOp-like situations work well: the Christian community at the Evangelical college where I studied, as well as various Catholic ministries. While there were still some institutional problems associated with trying to set boundaries in the community, at my college I experienced a community that was formed around Christianity as a joyful and meaningful way of life, not just something that desperately needs preservation. I found friendships that I am certain were God’s way of saving my faith. The success of this community was partly because professors designed our education to mitigate the intellectual and spiritual ill effects of the fundamentalist communities many students were raised in. In general, I think intentional community must have the flexibility to allow for all the flaws and sins of human nature, because rigidity leads to the worst abuses.

I’ve said nothing you haven’t heard before, but the moral of my story is to encourage you to carefully consider the mistakes of the ‘Benedict Options’ that have already been tried, lest all you have to show for the BenOp is a future generation of Rachel Held Evanses. However, with careful attention to the structure of the community, it may truly be possible to for people create Benedict Options that truly embody what you envision. Since I’m a current resident of [place withheld for privacy reasons], it would make me terribly happy to see some sort of BenOp community forming around here! This also leads me to the thought that the Benedict Option must not only appeal to educated middle-class people. I find comfort in sharing some of the difficult aspects of my story with you because, in a way, it expresses a hope for what you want to see realized in Benedict Option communities, which is the realization of abundant life.

What a great and encouraging e-mail. I also received this from another reader, this one an academic:

I’ve seen you wonder on many occasions about how to avoid fundamentalism in BenOp communities. I’d like to give you my thoughts on this, as someone who is a cross between a sociologist and a moral theorist. What I have to say boils down to a pithy motto: “There are no fundamentalists on feast days.”

You should look more deeply, I think, at Philip Rieff. His sociological theory contrasts interdicts (“thou shalt nots”) against remissions (releases from interdictory controls). Rieff is concerned about how an interdictory culture becomes as remissive one, as he believes our culture has become. But he does not stress that the preservation of authority depends on the proper combination of interdicts and remissions. A robust and valid, respected and legitimate authority has the power to issue interdicts, but the continuity of the respect and legitimacy that it inspires depends on the presence of remissions. A good authority allows times of relaxation from the rules, whereas an authority that intensifies its interdicts without allowing for releases becomes tyrannical.

What we call fundamentalism, what Evangelicals are so scared of, is an authority that is all interdicts and no remissions, all rules and pressure to conform without respite or breaks. It is a pressure that allows no rest – think of Israel in Egypt (Ex. 5).

The strange thing about Protestantism is that it has neither fast days nor feast days. Orthodoxy, which both of us practice, of course has these. We are nearing the fast of the Nativity, which ends in the feast week of Christmas. We fast laboriously during Lent, but then we celebrate Pascha. Can a fundamentalist celebrate the paschal feast? Can a fundamentalist celebrate Christmas as a feast week? No! This is because the fundamentalist does not allow for the interchange of interdicts (eg, fasting requirements) and remissions (feast days), but lives in a church that has abolished both fasting and feasting, as Protestantism by and large has, and replaced these with a stricter moral and doctrinal code, a demand of complete conformity with a different moral standard that is still called Christian.

How do you avoid fundamentalism? Insist that a BenOp community have releases from controls; insist that it have feast days, times of relaxing the rules. Orthodoxy is hard, but it is also gentle, which is to say that it knows that believers must have rest from their work. Fundamentalism is the abolishment of rest, the abolishment of freedom – and thus it is harder, in some ways, than Orthodoxy.

Long live fasting and the discipline of the body for prayer; long live feast days as well, so that the God for whom we fast and to whom we pray retains his character in our lives as merciful.

I hope you find this helpful.

I do! It says to me that one practice that Evangelicals can adopt from the early church (practices still observed in Orthodoxy) is feasting and fasting according to the Christian calendar. Evangelical readers, help me out here: is there any theological reason that you cannot observe periods of fasting? (By “fasting,” Orthodox Christians don’t mean doing without any food, but rather abstaining from meat and dairy, and, in some cases, large meals). Maybe some Evangelicals see it is a matter of works-righteousness (i.e., trying to work one’s way into heaven), but remember, Jesus fasted too. Besides, the point of fasting is to train the body to put spiritual goals ahead of bodily desires.

The first reader’s letter is a great reminder to me, who has never experienced fundamentalism, why it is so dangerous. It offers a “total solution” to the problem of human freedom. Let me quote again Isaac Bashevis Singer:

The powers that assail us are often cleverer than every one of our possible defenses; it is a battle which lasts from the cradle to the grave. All our devices are temporary, and valid only for one specific attack, not for the entire moral war. In this sense I feel that resistance and humility, faith and doubt, despair and hope can dwell in our spirit simultaneously. Actually, a total solution would void the greatest gift that God has bestowed upon mankind – free choice.