Catholic Triumphalism, Part II

Matthew Schmitz sent this reply to my “Catholic Triumphalism” post. He has given me permission to post it:

Thanks for your frank pushback. it’s helped me clarify my thoughts while helping me see some of the deeper complications of the matter.

I understand your argument that ordaining married men could help reduce the toleration of active and predatory homosexuality in the priesthood. This may well be right, but recent developments reduce the force of this argument. When men like McCarrick took holy orders, the priesthood was one of the only fields of action for an ambitious young man who knew that he didn’t like women. Now that has changed. The closet has been demolished by Lawrence, Windsor, Obergefell, and accompanying cultural changes. lf I’m a young man attracted to men in the year 2018, the priesthood is going to be a less attractive option to me than it would have been in 1958. This remains true even if one fully accepts Catholic teaching and doesn’t want to live an active gay life. Members of Courage and of the Spiritual Friendship circle have, despite their differing approaches, both shown that it is possible to be gay (or same-sex attracted, or what have you) and faithfully Catholic. Meanwhile, the priesthood has lost much of its social prestige. This, too, ought to weed out young men who do not really have vocations but are only entering it for extrinsic reasons (including ones related to their sexuality). Would someone as ambitious as McCarrick become a priest today? It’s hard to say.

Arguing in favor of celibacy (which isn’t strictly necessary for the priesthood) may seem like dumb Roman intransigence, but I’m inclined to it because it touches on the nature of the Church and its relation to the state. As Johann Adam Möhler argued, the celibacy of the priesthood is a sign of the “non-unity of Church and State.” By remaining celibate, Catholic priests are freed from the worldly concerns into which all family men necessarily enter. Celibacy is “a living testimony of faith in a constant outpouring of higher powers in this world and of the omnipotent rule of truly infinite forces in the finite.” Interestingly (and here you may agree with him) Möhler links papal primacy with celibacy. He believe that both preserve the Church’s independence from the state. Grant Kaplan argues that celibacy remains essential for resisting the subjection of Church to state. Certainly the churches that have made celibacy optional—Lutheran, Orthodox, and Anglican—have tended toward Erastianism.

Given the weight of these considerations, I would first want to exhaust other options—and I believe the Church has barely explored them—before giving up clerical celibacy. I also suspect that the collapse of the closet and loss of priestly prestige will render this a moot point. That said, many Catholics think as you do, and at the upcoming Amazonian synod, the view you share with them may well carry the day.

As for my argument that Catholic claims are loftier, and so Catholic sins are more scandalous … well, my point is a simple one. To whom much is given, from him much will be expected. As non-Catholics recognize, the Church makes some big, brassy claims for itself. It says that it is the ark of salvation, that what its human leader binds on Earth will be bound in Heaven. Anyone who believes these claims should be especially scandalized when the members of that Church fail.

Here you describe what happened to your belief in those claims:

I entered Orthodoxy with far lower expectations about the institution and the clergy than I had in Catholicism. I was naive about the Catholic institution, and saw in retrospect that I idolized it to a certain degree. Because I believed what the Catholic Church said about itself, I set myself up for a very big fall. Catholic friends who were not as idealistic about the Catholic Church as I was managed to come through the scandal fine.

As I understand it, you think that Catholics who believe what the Church says about itself will end up idolizing the institution, and set themselves up for a fall if they’re honest about clerical sin. Whereas certain friends of yours who are less idealistic—who, I take it, do not really accept those claims—are immune from such disappointment. As someone who does accept those claims, and who does want to be honest about Catholic sins, I hope (and believe) that you are wrong. In any case, those of us who maintain those claims must be especially vigilant in opposing Catholic sin, and sympathetic to those (like you) who are rightly scandalized by it.

Thanks for that, Matt.

First, I should clarify for readers that the Catholic Church’s practice of clerical celibacy is not a doctrine, but a discipline. If Rome changed its policy, that would not imply doctrinal changes. It would still be a very big deal, obviously, but there are no real theological impediments to doing so, as far as I understand.

Second, I don’t want to be understood as saying that Rome should get rid of celibacy. I don’t have an opinion on it, actually. I have seen in Orthodoxy the benefit of a married clergy (Orthodox bishops are required to be celibate), but I have also seen, from the side of a church with married clergy, the benefit of having unmarried clergy. There really isn’t a flawless solution. Both practices come with their own benefits and drawbacks. I believe that Rome will inevitably have to relax the discipline because of the priest shortage, but Catholics who look forward to the marriage option for priests shouldn’t assume that that will solve all problems.

As to Matt’s second point, I recognize that as a psychological and, I guess, sociological factor, but not as a theologically dispositive one. That is, it is certainly true that having great expectations of a Church makes the Church’s failures to live up to those expectations especially hard to take. Had the Roman church not made such grand claims for itself, as Matt elaborates, its failure to live up to them would not have landed as such a blow to me, and to others. A series of blows, actually: for me, events from early 2002 until early 2006, when I definitively left Catholicism, were like Muhammad Ali rope-a-doping George Foreman. By the time the bell rang, so to speak, the idea that the Catholic Church had the spiritual authority that it claimed was implausible to me. I honestly did not see how it could be that way. I thought I had had a good understanding of its history, and what the history of papal and hierarchical corruption meant. Those things were abstractions, though. It is one thing for Alexander VI Borgia to make his son an archbishop, and that son to host an orgy in the Vatican; it is another when you discover that your own bishop facilitated multiple clerical molestations of minors in your own diocese, and sent his lawyers after victims and their families seeking justice.

Strictly speaking, none of those things negate the truth claims of the Church. But they can have the effect of making it difficult to impossible to take those truth claims seriously.

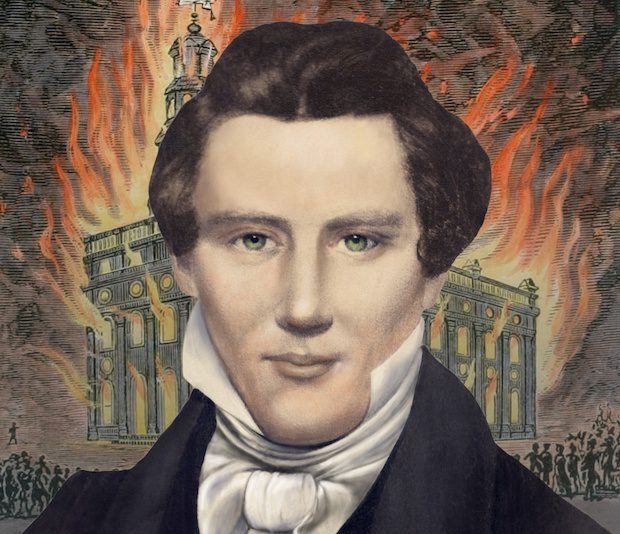

Think of the example of the Mormons. The Latter-Day Saints Church also makes massive claims for itself. It says that it is the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ, and that its foundational tome, the Book of Mormon, is a revelation from God on par with the Bible. Certainly a Mormon would see this as unjust and plain wrong, but I have never taken the time to examine the case for Mormonism seriously. (Nor for Islam, or any number of Christian churches.) That’s because the Mormon claims are impossible to believe on their face, at least to me, though obviously my own limitations in that way come from the fact that I was raised within historical Christian orthodoxy, and have spent most of my adult life as either a convinced Roman Catholic or a convinced Orthodox Christian. If I see grotesque corruption in the ranks of the Mormon hierarchy, I may be grieved on behalf of faithful Mormons, but I don’t regard that corruption as vindication of Mormonism’s truth claims. Nobody outside the Mormon church would say, “Wow, look at how rotten the LDS leadership is, even though they claim to be the exclusive voice of God on this earth. They must really be what they say they are.”

Now, for faithful Mormons, deep corruption within their church’s leadership would probably spark a crisis of faith akin the the crisis of faith I had as a Catholic. Believe me, I can understand that. I can agree with Matt Schmitz that the subjective experience of being a member of a Church that makes such exclusive, totalist claims makes challenges to those claims stemming from internal corruption a much deeper personal crisis than it would be for, say, a megachurch Evangelical. The revelation of evangelist Jimmy Swaggart’s sexual corruption no doubt caused a lot of pain for his followers, but it’s not likely that it caused any of them to doubt basic Protestant theology. Protestants simply do not make the same claims for the role and meaning of the institutional church that Roman Catholics do. Matt’s point makes sense to me if we’re talking about the subjective experience of scandalized Catholics, but I can’t see how the loftiness of Catholic ecclesiological claims makes the failure of Catholics to live up to the responsibilities entailed by those claims somehow a validation of those claims.

I’ve written here on a number of occasions about a bishop who said to me, in 2002, that he did not understand why, if I had lost confidence in the bishops’ ability to handle the scandal, that I remained a Catholic. I responded at the time that I remained a Catholic because I believed that Catholicism was true, and that those truths did not require me to have faith in the holiness and competence of the episcopate. I wonder, though, if that bishop understood something intuitive that I did not. It is possible, in theory, to retain one’s Catholic faith despite having lost trust in the bishops and the clergy, but it requires a lot of internal effort. Maybe not at first, but when you see filth uncovered time and time again, and little to nothing changes — well, it becomes harder and harder to believe that the Catholic Church is what it says it is. Finally you may become permanently disillusioned. You may leave the church, or you may stay, but become deeply embittered (I’ve known people like that), or may live as if the bishops and the clergy are in some way enemies of the faith — a very strange and painful place to be as a Catholic, and unsustainable in the long run for most of us.

Or, by God’s grace, you might find your way to a healthy place within a corrupt system, maintaining your spiritual balance while not lying to yourself about the reality of the institution’s failures. Most of my close Catholic friends seem to me to have achieved just this state of equilibrium, living in a condition of what we Orthodox call “bright sadness” — the particular joy we experience during Great Lent. I honor them for that. It was not something I could have done. I tried. I have also attempted to live my life as an Orthodox Christian in part as preparation for being able to do that should I be put to the test by a similar scandal within the Orthodox Church.

To sum up: I agree with Matthew Schmitz that as a psychological and sociological matter, the loftiness of Catholic claims makes the grave sins of the Catholic hierarchy and priests that much harder to endure. True! I appreciate his clarification in this follow-up post. It turns out that there is not the distance between our positions that I initially thought.

Where I still disagree with him is on these points from his original column:

This reflects a truth acknowledged by both Catholic and ex-Catholic alike. The Church proclaims a higher, more demanding teaching than any other religious assembly. Because Catholic aspirations are higher, Catholic sins are always more shocking. Corruptio optimi pessima – or as DH Lawrence put it, “The greater the love, the greater the trust, and the greater the peril, the greater the disaster.” …

This horror at the corruption of the best is the stance of the ex-Catholic. Despite the infamies that rightly enrage them, these ex-Catholics have not been able to shake a residual belief in the Catholic faith, a recognition of the nobility of the Catholic creed. If only because they retain this belief, I hope they will come back.

Boldface emphases mine. Matt imputes value to Catholic institutional self-understanding that begs the question. A more neutral, accurate characterization is not that Catholic aspirations are “higher,” and that its institutional self-understanding is the “best,” but that these things are more totalizing in Catholicism than in other religions. The Mormon example shows the weakness of Matt’s claim here. A fallen-away Mormon who once truly believed may well find it more painful to bear that loss than, say, a fallen away Mainline Protestant. But that pain says nothing about the truth or falsity of the Mormon Church’s claims — nor, when it happens to a Catholic, does it tell us anything about the ultimate truth or falsity of the Roman Church’s claims.

I will end by saying something about the fact that the Orthodox Church also makes massive claims for itself, like Catholicism. But as this is an aside from my response to Matt Schmitz, I will put it below the jump.

[Update: some of you have been unable to access the material below. I’ll take out the coding for the jump — sorry for the hassle. — RD]

I don’t think that these, or the corruption of Orthodox bishops and clergy, establish the truth or falsity of Orthodox claims. Yet Matt Schmitz’s post has made me think about why the prospect of Orthodox corruption doesn’t shake me as an Orthodox believer the way Catholic corruption shook me as a Catholic.

I’ve said in this space that it’s because 1) I lowered my expectations of the hierarchy and clergy, and 2) I have worked hard to govern myself to avoid the kind of clericalism and triumphalism that, as a Catholic, set me up for a big fall. But thinking further about it, I believe there’s a third factor.

The Orthodox tradition is far more stable in late modernity than the Catholic tradition. I didn’t see this from the outside, as a Catholic; I assumed that Orthodoxy, because it had an ecclesiology close to Catholicism’s, was more or less Catholicism without a pope, and articulated in a Greek, Slavic, or Arabic accent.

But seen from within, it looks very different. Having spent almost as much time as an Orthodox — 13 years — as I did a Catholic, I understand better the meaning of this saying: “Catholicism is an institution with a way of life attached, but Orthodoxy is a way of life with an institution attached.”

An Orthodox Christian can go about his life without having to pay the slightest attention to his bishop, because he can have faith that the bishop isn’t going to pull any funny stuff liturgically or doctrinally. The bishop may end up being a thief, a puppet of political leaders, or otherwise corrupt — but he’s not going to mess with the liturgy or the doctrine. A figure like Pope Francis is unthinkable within Orthodoxy. The turmoil of the Second Vatican Council and its aftermath is also entirely unknown and alien to Orthodoxy. It is certainly the case that Orthodoxy’s besetting sins include ethnic exclusivism and antiquarian smugness — the late Orthodox priest Alexander Schmemann wrote critically about these things in his journals — but the kinds of things that put intellectually engaged conservative Catholics in permanent battle mode simply aren’t present in Orthodoxy.

That doesn’t make Orthodox ecclesiological claims true, of course. But if I were to discover that Orthodox bishops or priests were corrupt, that news, as terrible as it would be, would strike me as one who is embedded within a stable, largely uncontested tradition. I believe that if I were to discover something as horrible as the systemic cover-up of sexually abusive priests by the hierarchy, I would be far, far better able to absorb it without my commitment to Orthodoxy being threatened. My experience of Catholicism was defensive within the Church from day one; my experience of Orthodoxy has not been that way at all.

One big reason has more to with my own decision, at the beginning, to focus on Orthodoxy as a way of life, and not an intellectual phenomenon. As I have said many times, one of my greatest errors as a Catholic was to live primarily as an intellectual within the church. I made the mistake of thinking that if I mastered the intellectual dimension of the faith, I would be safe. It was a dangerous form of hubris that caused me to neglect the disciplines that would have strengthened me spiritually. This is why I urge faithful orthodox Catholics to take up the Benedict Option in their own lives. Take nothing for granted.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.