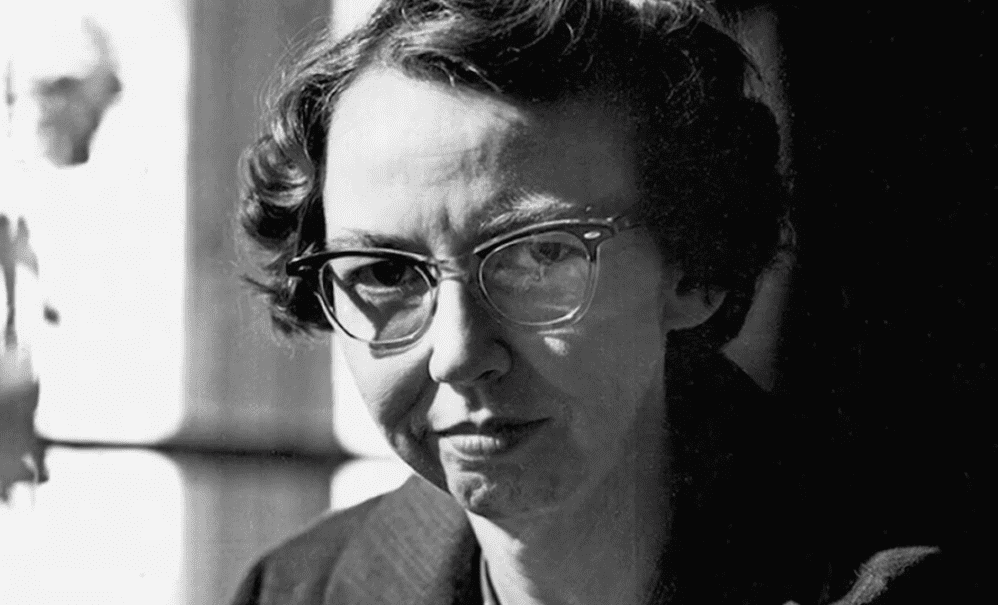

Cancelling Flannery O’Connor

Thirteen years after naming a new residence hall at Loyola University Maryland in honor of the Catholic author Flannery O’Connor, Jesuit Father Brian Linnane, the university’s president, removed the writer’s name from the building.

The structure will now be known as “Thea Bowman Hall,” in honor of the first African American member of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration.

Bowman, a Mississippi native, was a tireless advocate for greater leadership roles for Blacks in the Catholic Church and for incorporating African American culture and spiritual traditions in Catholic worship in the latter half of the 20th century. Her sainthood cause is under consideration in Rome.

Jesuits, man.

You might find this hard to believe, but once upon a time, the Jesuits had a reputation for being the most intellectual of the Catholic Church’s orders.

A reader sent me this letter going around academic circles:

Dear Friends,I hope this finds you well. Please forgive this group email, but I wanted to communicate as quickly as possible about this time-sensitive issue.As you may have heard, the president of Loyola University Maryland has decided to remove Flannery O’Connor’s name from one of its buildings on campus. The impetus behind the initiative was Paul Elie’s article on O’Connor and race that appeared in the June 22nd NEW YORKER. (I have a lot to say about that article, but not in this space.) A Loyola student read the piece, contacted me, since my name and a “review” of my new book (RADICAL AMBIVALENCE: RACE IN FLANNERY O’CONNOR) appears in the article, and asked if I would help her with the process. I was, as you might imagine, horrified, and advised her not to go ahead with her petition, but she felt very strongly about the issue and, obviously, won over the president.I, along with a group of O’Connor scholars, professors, and writers, have drafted and are circulating a letter of protest to the president. Among our 70 plus signatories thus far are Alice Walker, Richard Rodriguez, Mary Gordon, and an impressive gathering of distinguished O’Connor scholars and critics. The letter appears below. If you would like to add your name to the list of signatories, we would greatly appreciate your support. Also, if there are other people you might like to pass this along to, please feel free–or, if you prefer, please send their names to me.Thanks for your consideration & prompt attention to this time-sensitive matter. Not to be too dramatic, I feel as if we are poised at a crisis point. Cancelling confederate generals and taking down civil war monuments is a very different matter from cancelling writers, thinkers, and artists, none of whom were ever presumed to be saints or paragons of conventional virtue. This is antithetical to university culture and life. Few, if any, of the great writers of the past can survive the purity test (which is a Puritanical rather than a Catholic impulse). If a Catholic Jesuit university effectively “cancels” Flannery O’Connor, why keep Sophocles, Dante, Shakespeare, Dostoyevski and other racist/anti-semitic/misogynist writers? No one will be left standing. Cheers & Onward,AngelaP.S. I realize this letter may not reflect the perspective of each person I have included in this email. Please feel free to send a letter of your own devising to President Linnane, if you prefer. In fact, the more letters he receives, the better. Richard Rodriguez, for instance, is signing on and, in addition, is sending his own–others have indicated they intend to do the same.Here are the president’s email addresses: blinnane@loyola.edu & president@loyola.edu. Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, Ph.D.Associate Director

The Francis and Ann Curran Center for American Catholic Studies

Fordham University

Here’s a link to the Paul Elie piece that provoked this cancellation. Elie writes that O’Connor — a rural Georgia white woman born in 1925 — had a “habit of racial bigotry.” Excerpts:

Those letters and postcards she sent home from the North in 1943 were made available to scholars only in 2014, and they show O’Connor as a bigoted young woman. In Massachusetts, she was disturbed by the presence of an African-American student in her cousin’s class; in Manhattan, she sat between her two cousins on the subway lest she have to sit next to people of color. The sight of white students and black students at Columbia sitting side by side and using the same rest rooms repulsed her.

It’s not fair to judge a writer by her juvenilia. But, as she developed into a keenly self-aware writer, the habit of bigotry persisted in her letters—in jokes, asides, and a steady use of the word “nigger.” For half a century, the particulars have been held close by executors, smoothed over by editors, and justified by exegetes, as if to save O’Connor from herself. Unlike, say, the struggle over Philip Larkin, whose coarse, chauvinistic letters are at odds with his lapidary poetry, it’s not about protecting the work from the author; it’s about protecting an author who is now as beloved as her stories.

More:

After revising “Revelation” in early 1964, O’Connor wrote several letters to Maryat Lee. Many scholars maintain that their letters (often signed with nicknames) are a comic performance, with Lee playing the over-the-top liberal and O’Connor the dug-in gradualist, but O’Connor’s most significant remarks on race in her letters to Lee are plainly sincere. On May 3, 1964—as Richard Russell, Democrat of Georgia, led a filibuster in the Senate to block the Civil Rights Act—O’Connor set out her position in a passage now published for the first time: “You know, I’m an integrationist by principle & a segregationist by taste anyway. I don’t like negroes. They all give me a pain and the more of them I see, the less and less I like them. Particularly the new kind.” Two weeks after that, she told Lee of her aversion to the “philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind.” Ravaged by lupus, she wrote Lee a note to say that she was checking in to the hospital, signing it “Mrs. Turpin.” She died at home ten weeks later.

Those remarks show a view clearly maintained and growing more intense as time went on. They were objectionable when O’Connor made them. And yet—the argument goes—they’re just remarks, made in chatty letters by an author in extremis. They’re expressive but not representative. Her “public work” (as the scholar Ralph C. Wood calls it) is more complex, and its significance for us lies in its artfully mixed messages, for on race none of us is without sin and in a position to cast a stone.

That argument, however, runs counter to history and to O’Connor’s place in it. It sets up a false equivalence between the “segregationist by taste” and those brutally oppressed by segregation. And it draws a neat line between O’Connor’s fiction and her other writing where race is involved, even though the long effort to move her from the margins to the center has proceeded as if that line weren’t there. Those remarks don’t belong to the past, or to the South, or to literary ephemera. They belong to the author’s body of work; they help show us who she was.

I think Elie makes a fair criticism. I love O’Connor, and hate that there was any flaw in her character, but she was a woman of her time and place. It is breathtakingly anti-intellectual, and anti-art, to believe that this character flaw negates her monumental literary achievements. There is no American Catholic fiction writer greater than Flannery O’Connor, and there the Loyola University of Maryland, a nominally Catholic institution, is going to shit on her because she held ugly opinions that were overwhelmingly common in mid-century rural Georgia. As others have pointed out, O’Connor’s work — especially the story “Revelation” — shows an artistic conscience struggling with her sinful nature. Ruby Turpin is the villain of that story. That O’Connor saw some of herself in that villain only makes her human, and adds to the moral and spiritual drama of her life. Of all O’Connor’s characters, the two I struggle against most in myself is Asbury (“The Enduring Chill”) and Mrs. Turpin — not because of her racism, but because of her pride. “Revelation” is a stunning rebuke of pride, and the pride that undergirded the racism of people like Ruby Turpin. One can learn more about what it means to be a Christian — and a Christian under judgment — by reading one story of Flannery O’Connor’s than by reading a bookshelf full of tepid politically corrupt work by writers who never give evidence of having had a sinful thought, or an actual heartbeat.

To live in the South — or at least to have grown up in the South in my generation — is to live with the awareness that most of the older people you know have a great blindness on the subject of race. This is a moral failing that cannot be separated entirely from the goodness in their hearts. Nor, though, can what is good and even great in them be separated from what is sinful and unworthy. This is true of every man and woman who walks this earth, but you can see it so vividly in the South. What a terrible thing this is, what these Philistines are doing to O’Connor. As Angela Alaimo O’Donnell rightly says, if Flannery O’Connor, despite her artistic greatness, gets canceled, who can possibly stand?

One big reason these Jacobins, especially the young ones so full of savage righteousness, keep winning is that older people who ought to know better — like the president of Loyola of Maryland — keep surrendering to the mob.

A university — even a Catholic university — is not a seminary. Flannery O’Connor was chosen for this honor not because she is a saint, but because she was a peerless American Catholic writer of fiction. Great art comes from suffering and struggle, including struggle against one’s own sinful nature. O’Connor herself, in her own lifetime, had to contend with people who thought it was wrong for a nice Catholic woman like her to write stories that had such violence in them. Those were ordinary pew-sitters; you can’t really be surprised by that. What is surprising, indeed shocking, is that now educated Catholic opinion, at least at Loyola of Maryland, now shares the same philistinism as the 1950s laity.

This is a sign to high school students about whether or not Loyola of Maryland is a hospitable community to free thought and scholarship.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

I am a long-time reader of your blog and books. I have long believed you to be a Jeremiah-type who warns those with ears to hear. My eyes have been opened to many things because of your blog. Having said that, I must take exception to your constant willingness to excuse the ugliness of white Southerner’s behavior towards blacks. Let me narrow the focus to Christian or Bible-believing whites. Since the Bible and Holy Spirit were available to them then, as now, how can blindness be honestly claimed as you did in the Flannery O’Connor article? Scripture, specifically, 1 John 4 speaks of the expectation of Christian behavior toward others; Verses: 19-21 lay things out with ZERO POSSIBILITY of any other way:

19 We love because he first loved us.20 Whoever claims to love God yet hates a brother or sister is a liar.For whoever does not love their brother and sister, whom they have seen, cannot love God, whom they have not seen.21 And he has given us this command: Anyone who loves God must also love their brother and sister.

In other words, if we say we love God, then we cannot act in hatred toward our fellow man or we are liars and Revelation states that liars end up in the Lake of Fire. My point is that you are too quick to excuse the behavior of Southerners by calling it blindness. Please at least consider that it was not, in fact, blindness, but rather, complete and willful rebellion to God, to whom we will give account. Furthermore, God has always given people courage to go against the prevailing attitudes of the day in obedience to His Word.

I responded to the reader:

[Name], I’m not excusing O’Connor’s views. I believe they were sinful. Furthermore, I believe that she knew they were sinful, and that her story “Revelation” is her acknowledgement of that. She struggled within herself, it seems to me.

I grew up in the Deep South, as you know — O’Connor’s world was the first time I had ever encountered in fiction people who were recognizable to me. You could not separate the good from the evil in most white folks in my town. When I was a young adult, and came to understand the evil of racism, I judged all the whites older than me harshly for their sin.

Then, around 2012, after I had moved back to my hometown, I learned of what was almost a white riot on the courthouse lawn, right in my own town, over a black man trying to register to vote. This was in 1963, four years before I was born. I had never heard of it. People in my town just never, ever talked about this stuff — and I can imagine why; they must have been ashamed of it.

I had to face the fact that a lot of the men I grew up there admiring were no doubt in that mob that day, screaming at the black pastor. But here’s the thing: I had to recognize that had I been born a generation earlier in that town, I would either have been with them, or at the very least would not have found the courage to condemn them. My mother and my late father were born in 1943 and 1934, respectively. They grew up in that town. Neither was very religious, but had they gone to church, they never would have heard a word from the local white churches condemning the evil of racism. Television wasn’t invented then, of course, and most people that far out in the country didn’t take the Baton Rouge newspaper — which, in any case, wouldn’t have challenged the racist order. There was radio, but neither would it have challenged the racist order.Where would my mom and dad’s generation, and my grandparents’ generation, have received an alternative narrative to white supremacy? Exactly nowhere. They were totally acculturated to it and by it, and not even the white churches took a stand. White supremacy was completely normal. All the institutions and social structures of that world told white people living within them that evil — the evil of racism — was good. Just part of the natural order of things. Had I been of that generation, I would have probably been standing there on the courthouse lawn with the mob, yelling for the head of that black pastor. Had I been a Jew in Jerusalem, A.D. 33, I would have been in the crowd shouting, “Crucify him!”I’m old enough to have received some of that myself. My generation was the first in our town to go through totally integrated public schools. I remember the strangeness of being around black people, as a child. My town was half black, and you saw black folks everywhere, but there was something different about going to school with them. They seemed like aliens to me. There was a head lice outbreak in my elementary school, and I recall on the playground, us frightened white kids assuming that the bugs must have come to us through the black kids. It had to be true — they were dirty, because they were black. Then some kid said (falsely) that their mama told them black people can’t get head lice, on account of the texture of their hair, and I recall the rest of us — third graders — being crestfallen at the injustice of this.

Crazy, right? I think so. Here’s the thing: I cannot ever recall either of my parents instructing me in this malignant point of view. I would be surprised if anybody’s parents did. Yet there we were, believing it. We had absorbed it from the ambient culture. Mind you, we were only six years into integrated schools by then, and none of us kids, white or black, had any real clue about the history of our town, our part of the world, our country. Get this: the only vector for teaching that racism was wrong was television. That’s it! I can remember having real cognitive dissonance as a child (I watched a lot of TV), getting the message that racial discrimination was evil, but seeing so much racial bias built into the way we white people approached the world. I’m trying to think if I ever asked my folks about it, but I probably didn’t. It was just one of those mysteries of life. It did not occur to me to question any of it until I became a teenager, and started learning history on my own.Reading Flannery O’Connor in high school (eleventh grade) was part of my moral education. “Revelation” was exactly that for me. I well remember first encountering Mrs. Turpin in the doctor’s waiting room, sorting out the world among good people and bad people, with black people on the bottom. I could have met someone like her in Dr. Gould’s waiting room in my hometown as a child. And the black farm workers who spoke to her with false flattery — I had heard black people talking to white people many times in the same language. Were they not sincere after all? No, they probably weren’t. But now I understood better why they had to be insincere: as a means of protecting themselves from white violence. I also recognized in myself, and a lot of people I knew, Mrs. Turpin’s prideful judgment towards white people who weren’t as respectable as she believed herself to be.If I ever get around to writing fiction, and write from the heart of my own experience, I will have to confront that pride within my own heart. It doesn’t manifest itself in the same way it did in Ruby Turpin, or the men and women among whom I grew up. But it’s there. I am much more likely to be the kind of person who thinks, in a self-satisfied way, “I am glad I am not like those trashy white people who hate blacks.” What I should be thinking is, “If I do not hate black people, it is only because of the work of redemption and sanctification that Christ has done within me. Lord, have mercy.”

But really, there is no end to our repentance. Nobody can be formed in the culture I was without having been deformed by it, in a way that requires constant vigilance and repentance. On the other hand, I was given so many gifts by that same culture, a raising that taught me to be more loving and humane. That this gentling way of life came with a terrible way of life regarding our black brothers and sisters is our tragedy, and even a paradox. If I wanted to cut the good from the evil out of my inheritance, I might as well slice off parts of my own body. Remember the immortal insight of Solzhenitsyn’s:“The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained.”

One reason why I hate so much of this “antiracism” movement and activism is that it’s built on a false image of humanity’s capacity for sin. It denies that black people, as human beings, are just as capable of sin as the rest of us. Give them the kind of power that whites held for so long, and they will use it sinfully, precisely because they are human. The black man may not struggle with the sin of racism per se, but he might struggle with the sin of hating his white neighbor over the cruelty whites committed against blacks for so long, or possibly the privileges whites today have accrued because of that unjust social order. He might even be tempted to avoid looking into his own heart, and assessing his own life, and taking responsibility for his own failures, finding it easier to blame the white man for all his suffering. I assure you that plenty of poor and working-class white people over the generations have found in black people convenient scapegoats in this way. You can meet white people like that in the stories of Flannery O’Connor.

I mentioned earlier that I see myself in the character of Asbury, from O’Connor’s story “The Enduring Chill.” Asbury is an educated young intellectual who has to live back on the farm with his mother (note well that O’Connor lived on a farm with her mother). He looks down on his mother for her ignorance, especially her racism. What we see in Asbury, though, is a man who is full of pride and contempt — and that same pride and contempt leads him to a bad place. None of this is to vindicate his mother’s racism, heaven knows, but rather it is to show that Asbury thought himself so much better than his simple country mother because he did not have the racism that she did. Or didn’t he? He valorized the black farm workers, and saw them not as men in their own right, but rather as screens onto which he could project his spite for his mother. And this gets him into trouble.

Asbury is me at my worst. Asbury is liberal antiracists at their worst. It is impossible to read this story, knowing that O’Connor was an educated young woman living at home with her mother Regina, who drove her crazy sometimes, without seeing it as O’Connor’s judgment on her own arrogance.

Is it so difficult for you to understand the complexity of the human heart, [Reader]? My ancient Aunt Hilda — she was the aunt of my grandmother — was still alive when I was a boy. She was born in 1893, in our settlement in the countryside. Her father, Columbus, had been a Civil War soldier. An amazing woman! She and her sister Lois were two of the most cosmopolitan people I ever knew. They served as Red Cross nurses during the last year of World War I, in France. Hilda was on the Champs-Elysees when the armistice was announced. They filled me with these stories in their little cabin in an orchard when I was a boy.

Hilda had been a social worker in her career. When I was a kid, there was a poor black family living in a shack across the country road from us (Hilda and Lois lived nearby). Hilda was ardent and indomitable, what you would call today a social justice warrior. She was an Episcopalian who also was into palm reading. She decided that that family needed welfare, so she helped them commit welfare fraud. My father discovered this because as the chief public health officer in the parish, he shared offices with the welfare bureaucracy. It drove my dad crazy, because the man in that shack, the shiftless son of one of the old sisters who lived there, would not hold a job (my father tried to get him one), and stole from us at night. I can remember working out in the yard as a little kid, and seeing Wilbur, this guy, laying on his front porch across the road with his head hanging off, whiling the days away doing nothing, living off of the charity Aunt Hilda helped him get by defrauding the government.

Hilda died before I was old enough to understand any of this. I can well imagine that she thought that what had been done to black people by the unjust social order justified this relatively minor crime. But you could not tell Hilda what to do. She always knew better, and was completely blind to her own faults, which were many. She respected intelligence and cosmopolitanism, not character — and this proved to be her undoing. It’s a long story, one worthy of Flannery O’Connor. I bring her up to say that even though Hilda was willing to break the law to help a black family, she was not free of racism either. She and her sister — again, women born in the last decade of the 19th century, to a Civil War veteran and his wife — referred to black people as “darkies,” and sometimes “colored people.” Darkies — that was the polite word when they were young! To say “nigger” was a mark of unsophistication, of trashiness. My God, Aunt Hilda walked straight out of an O’Connor story.

Anyway, look: by our measure today, I’m sure Aunt Hilda was a racist. But how fair is it to judge her by our standards? I’d suppose that she was the only white woman in all of West Feliciana Parish to be willing to break welfare law to help a poor black family. Does that count for nothing? And yet, she was an arrogant woman whose arrogance, like Asbury’s, proved to be her Achilles heel later in life. What’s more, it would have been impossible for a white woman of her generation to have entirely escaped racial prejudice. Don’t you see how complex the human heart is? I watched that drama play out with my own eyes, as a boy. I had no idea what a gift it was.

Look, I’m going on too long about all this. I would say to you, [Reader], that reading O’Connor might help you to understand how you yourself act in hatred of your fellow man in ways that are hidden to you now. Original sin infects everything we touch. Flannery O’Connor knew she was under God’s judgment, as all of us are. She judged herself. But she also knew that she was under God’s mercy, as all of us who claim it are.

One Flannery O’Connor — a true artist who knew the human heart, and who knew the refining fire of God’s mercy — is worth ten thousand moralists for whom Goodness and Evil are simple, easy, and abstract. We are all blind, [Reader], every one of us — blinded by our families, blinded by our cultures, blinded by time and place, blinded by the human condition. None of us can escape it. It takes a lot of repentance to know how little you really know about yourself. It takes a mighty surrender to grace to gain the ability to see ourselves in the mirror just a little less darkly than we otherwise would. The journey through life is a journey into regaining our sight. Artists like Flannery O’Connor bring the light, though it may come cloaked in superficial darkness.

Does your conscience bother you? If not, why not? What are you not seeing that God sees? What are you not seeing that others around you see, but will not tell you?

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.