Out Of The Rubble, Hope

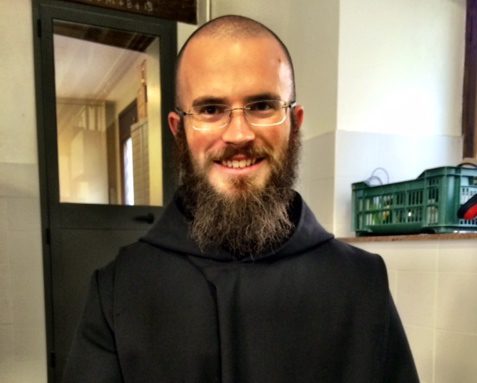

A new interview with Father Martin Bernhard, one of the Benedictine monks of Norcia. Excerpts:

“Now, we have the chance to really be like St. Benedict and those monks at the fall of the Roman empire,” said Bernhard. “When the culture and civilization [were] falling apart…morally, economically,” St. Benedict and his followers “had an opportunity to kind of be even a brighter light, a brighter beacon.”

“We kind of find ourselves in a similar situation,” he said, because the local tourism-based economy has greatly suffered and “a lot of people are out of their homes and out of jobs…and now we have an opportunity to rebuild in that context, not only [in a] culturally, morally challenged context, but an economically challenged context.”

The tragedy of the earthquake, and Norcia’s rebuilding efforts, can “show to the world that even when things go very badly or there are great difficulties around one, it doesn’t mean we have to give up hope,” said Bernhard. “The hope is that our music and our chant and our prayers and our beer and our liturgy can still be kind of given to the world and I think maybe even in a more authentic way because we will have suffered more in order to make it happen.”

Bernhard said the earthquake was the cause of “a great sense of a kind of fear and trust really in God’s providence and a great recognition of our littleness as humans.”

“When the ground shakes like it did it kind of strikes a kind of natural fear,” he explained. “You grow up your whole life thinking the ground you stand on is firm [and] it’s not going to move. But then when it starts to move, it seems like the whole world is kind of falling apart around you. And then with a lot of the tremors and everything that took place afterwards, kind of for days, you would think about, ‘if I put this here on the table, will it fall off?'”

Now you understand a bit better why the Norcia monks look at the ruins of their old monastery and the basilica and see in them a symbol of Christianity in the West. And therefore, you can see the scope of their rebuilding project. More from Father Martin:

Bernhard encouraged Christians seeking to create their own communities in the spirit of St. Benedict to pray together.

“Community life is not just a social gathering,” he said. “It’s also a moment of prayer, which has a social element because it involves more than one person.”

And read together, he recommended. “Choose good books. Choose good saints…study them together, talk about them.”

Read the whole thing. I think that Father Martin will be in Dallas next weekend for the big fundraising dinner for the monastery. Also, Father Cassian, the founding prior, and Father Benedict, the current prior. I’ll be the speaker. The dinner is sold out.

Last night, my Orthodox priest put me onto this 1968 lecture by the late Father Alexander Schmemann, titled “The Mission of Orthodoxy,” saying that it reminded him of The Benedict Option in some ways. All Christians can profit from this, I believe. Excerpts:

It is here that I must stress again the fundamental quality of American culture: its openness to criticism and change, to challenge and judgment. Throughout the whole of American history, Americans have asked: “What does it mean to be American?” “What is America for?” And they are still asking these questions. Here is our chance, and here is our duty. The evaluation of American culture in Orthodox terms requires first a knowledge of Orthodoxy, and second a knowledge of the true American culture and tradition.

One cannot evaluate that which one does not know, love, and understand. Our mission, therefore, is first of all one of education. We–all of us–must become theologians, not in the technical sense of the word, but in terms of vital interest, concern, care for our faith, and above everything else, in terms of a relationship between faith and life, faith and culture, faith and the “American way of life.”

Let me give you one example. We all know that one of the deepest crises of our culture, of the entire modern world, is the crisis of family and the man-woman relationship. I would ask, then: How can this crisis be related to and understood in terms of our belief in the one who is “more honorable than the cherubim and beyond compare more glorious than the seraphim. . . “–the Theotokos, the Mother of God, the Virgin?Where all this will lead us, I do not know. In the words of a hymn of Cardinal Newman: “I do not see the distant scene, one step enough for me.” But I know that between the two extremes–of a surrender to America, of a surrender of America–we must find the narrow and the difficult way of the true Orthodox Tradition. No solution will ever be final, and there is no final solution in “this world.”

We shall always live in tension and conflict, in the rhythm of victory and defeat. Yet if the Puritans could have had such a tremendous impact on American culture, if Sigmund Freud could change it so deeply as to send two generations of Americans to the psychoanalytical couch, if Marxism, in spite of all its phenomenal failures, can still inspire presumably intelligent American intellectuals, why can’t the faith and the doctrine which we claim to be the true faith and the true doctrine have its chance? “O ye of little faith …. ”

Marx and Freud never doubted, and they won their vicious victories. The modern Christian, however, has a built-in inferiority complex. One historical defeat pushes him either into an apocalyptic fear and panicking, or into a “death of God” theology. The time has come, perhaps, simply to recover our faith and apply it with love and humility to the land which has become ours. And who can do that if not those who are given a full share in American culture?

Two things, then, are essential: first, the strengthening of our personal faith and commitment. Whether priest or layman, man or woman, the first thing for an Orthodox is not to speak about Orthodoxy, but to live it to his full capacity; it is prayer, it is standing before God, it is the difficult joy of experiencing “heaven on earth.” This is the first thing, and it cannot be reached without effort, fasting, asceticism, sacrifice, or without the discovery of that which in the Gospel is called the “narrow way.”

And second, to use a most abused word, there must be a deep and real dialogue with America–not accommodation, not a compromise, for a dialogue may be indeed violent. If nothing else, it will achieve two things. It will reveal to us what is real and genuine in our faith and what is mere decoration. We may, indeed, lose all kinds of decorations which we erroneously take for Orthodoxy itself. What will remain is exactly the faith which overcomes the world.

In that dialogue we will also discover the true America, not the America which so many Orthodox curse and so many idolize, but the America of that great hunger for God and His righteousness which has always underlain the genuine American culture. The more I live here, the more I believe that the encounter between Orthodoxy and America is a providential one. And because it is providential, it is being attacked, misunderstood, denied, rejected on both sides. Perhaps it is for us, here, now, today to understand its real meaning and to act accordingly.

After a discussion of church history, Father Schmemann says:

Our situation today is once more that of crisis, and it is the nature of that crisis that is to shape the orientation of our missionary effort. The fundamental meaning of the crisis lies in the fact that the Christian world born out of Constantine’s conversion, and the subsequent “symphony” between the Church, on the one hand, and the society, state, and culture, on the other, has ended.

Please do not misunderstand me. The end has come not of Christianity, not of Church or faith, but of a world which referred, however nominally at times, its whole life to Christ and had Christian faith as its ultimate criterion. All dreams about its restoration are doomed. For even if Christians were to recover control of states and societies, that would not automatically make these societies “Christian.” What happened occurred on a much deeper level.

The fact is we are no longer living in a Christian world. The world we live in has its own style and culture, its own ethos, and, above everything else, its own worldview. And so far Christians have not found and formulated a consistently Christian attitude towards the world and its worldview and are deeply split in their reaction to it. There are those who simply accept the world’s view and surrender to secularism.

And there are those whose nervous systems have not withstood the shock of the change and who, faced by the new situation, are panicking.

If the first attitude leads little by little to the evaporation of faith itself, the second threatens us with the transformation of Orthodoxy into a sect. A man who feels perfectly at home in the secular and non-Christian world has probably ceased to be a Christian, at least in the traditional meaning of that term. But the one who is obsessed with a violent hatred and fear of the modem world has also left the grounds of the genuine Orthodox tradition. He needs the security of a sect, the assurance that he at least is saved in the midst of the universal collapse. There is very little Christianity and Orthodoxy in either view. If some forget that the Kingdom of God is “not of this world,” the others do not seem to remember that “perfect love overcomes all fear.”

And he concludes by calling for a new “movement” of people rededicated to the faith:

I have in mind a kind of spiritual profile of that movement and of those who will take part in it. To me, it looks in some way like a new form of monasticism without celibacy and without the desert, but based upon specific vows. I can think of three such vows.

1. PRAYER: The first vow is to keep a certain well-defined spiritual discipline of life, and this means a rule of prayer: an effort to maintain a level of personal contact with God, what the Fathers call the “inner memory of Him.” It is very fashionable today to discuss spirituality and to read books about it. But whatever the degree of our theoretical knowledge about spirituality, it must begin with a simple and humble decision, an effort, and–what is the most difficult–regularity. Nothing indeed is more dangerous than pseudo-spirituality whose unmistakable signs are self-righteousness, pride, readiness to measure other people’s spirituality, and emotionalism.

What the world needs now is a generation of men and women not only speaking about Christianity, but living it. Early monasticism was, first of all, a rule of prayer. It is precisely a rule we need, one which could be practiced and followed by all and not only by some. For indeed what you say is less and less important today. Men are moved only by what you are, and this means by the total impact of your personality, of your personal experience, commitment, dedication.

2. OBEDIENCE: The second vow is the vow of obedience, and this is what present-day Orthodox lack more than anything else. Perhaps without noticing it, we live in a climate of radical individualism. Each one tailors for himself his own kind of “Orthodoxy,” his own ideal of the Church, his own style of life. And yet, the whole spiritual literature emphasizes obedience as the condition of all spiritual progress.

What I mean by obedience here, however, is something very practical. It is obedience to the movement itself. The movement must know on whom it can depend. It is the obedience in small things, humble chores, the unromantic routine of work. Obedience here is the antithesis not of disobedience, but of hysterical individualism. “I” feel, “I” don’t feel. Stop “feeling” and do. Nothing will be achieved without some degree of organization, strategy, and obedience.

3. ACCEPTANCE: The third vow could be described, in terms of one spiritual author, as “digging one’s own hole.” So many people want to do anything except precisely what God wants them to do, for to accept this and perhaps even to discern it is one of the greatest spiritual difficulties. It is very significant that ascetical literature is full of warnings against changing places, against leaving monasteries for other and “better” ones, against the spirit of unrest, that constant search for the best external conditions. Again, what we need today is to relate to the Church and to Christ our lives, our professions, the unique combination of factors which God gives us as our examination and which we alone can pass or fail.

Read the whole thing. It’s really good.

As I write this, I’m receiving texts from a conservative Evangelical friend who said his pastor this past Sunday preached on life in “post-Christian America.” The pastor had not read my book, but he has read the signs of the times. He told his congregation that the disruptive changes in our society and culture are accelerating, and that Christians have to face this fact, and prepare for it. He’s right. But as Father Martin Bernhard reminds us, there is hope! We should not expect to avoid suffering, but should be prepared to face it like Christians (not Moralistic Therapeutic Deists), and to work by the Spirit to redeem that suffering. The Monks of Norcia are helping to show the way. Get to know their story.

UPDATE: Evangelical Friend texts this addition:

I should be clear that my pastor’s conclusion was very optimistic. He said we should see the changes as an opportunity, an expansion of our mission field.

He specifically said that all of the anti-Christian people are not our enemies. They are our mission field. They are victims of the Enemy.