The Secret History of Father Maloney

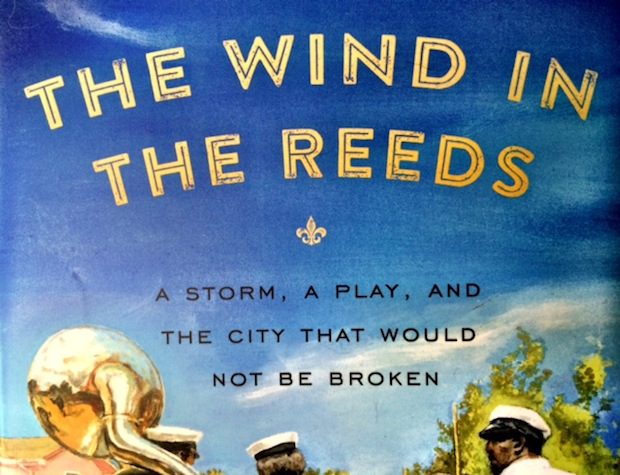

Today is the publication date of The Wind in the Reeds, actor Wendell Pierce’s memoir about his Louisiana past and Louisiana present. It’s a book about family’s rise out of slavery and Jim Crow. It’s a book about growing up in New Orleans, and building on the gifts of character and education his family gave him to study acting at Juilliard, and launch a career as a successful artist. It’s a book about how Hurricane Katrina destroyed the neighborhood that had nurtured him, and how he vowed to go home, to rebuild his childhood home, and to commit himself to bringing New Orleans back. It’s a book about the power of art to redeem our suffering and transcend our tragedies. It’s a book about faith, family, resilience, and the promise of America. It is a profoundly American, profoundly hopeful work, and I hope you will read it.

As readers of this blog may recall, it was my very great privilege to work with Wendell on The Wind in the Reeds (the title is a phrase from Waiting For Godot; Wendell played Vladimir in a nationally recognized 2007 production staged in the ruins of the Lower Ninth Ward, and repeated in the ruins of Gentilly). I wrote here about how the experience of working with Wendell on the book opened my eyes and changed my heart. I will blog more about the book over the coming week, but a conversation I had with my mom this morning prompts me to relate this story from Wind in the Reeds.

Mama told me about a white man in our parish who, back in the early 1960s, ran for a position on the local parish council (called the “police jury” in those days; it’s a Louisiana thing), and said as part of his campaign that blacks ought to be allowed to register to vote. The Klan paid a visit to his house one night and burned a cross in his yard — this, even though the man, who died many years ago, was a lifelong resident of the parish. It testified to how the regime of white supremacy terrorized not only blacks, but even whites who dared to challenge it. My mom said that the white man terrorized by the Klan recognized at least one of the men, even though they were wearing white sheets, because he recognized the man’s shoes. And because everybody in this small rural place knew everybody else, that white man had to live with the knowledge that his own neighbors were willing to commit acts of terror against him.

I’ve often wondered how I would have reacted had I been a grown man around here in those days. My mother’s story made me reflect on the kind of moral and physical courage it took for anybody opposed to white supremacy to stand up to it. I like to think that if more whites had done the right thing, white supremacy would have fallen sooner. Maybe it would have, but a tale like that helps me understand how hard it would have been for whites to have resisted. The immensity of the thing.

So, when Wendell and I were researching The Wind in the Reeds, we learned a fascinating story from his Uncle Lloyd (“L.C.”), who is now 81. It’s a piece of civil rights history that amazed both of us. Lloyd had never told Wendell the story, and it’s the kind of story that might have been lost to history.

Father Harry J. Maloney, a big, bluff Irishman from New York City, had given his life as a priest of the Josephites, a Catholic religious order founded by Rome in the 19th century to provide priests to serve freed black slaves in America. Believe it or

not, there were lots of Catholic slaves. In Louisiana, if the master was Catholic, his slaves were also baptized as Catholics. After the Civil War, they had no black priests, and the segregated culture made it impossible in most places for black Catholics to share churches with white Catholics. The Josephites dedicated their lives to serving African American congregations.

In 1948, the New Orleans archdiocese sent Father Maloney to Assumption Parish, where Wendell’s ancestors were living, to serve the black Catholics there. From the book:

“He was a great man,” Uncle L.C. said. “He opened the eyes of many people. Mamo and Papo [L.C.’s parents, and Wendell’s grandparents — RD] always said there’s something better coming by, and that something was Father Harry J. Maloney.”

As soon as he hit the ground, Father Maloney started building St. Augustine parish church, and a new school at St. Benedict the Moor for black children. L.H. [L.C.’s brother — RD] and L.C. stayed in the Catholic school system because Father Maloney organized a school bus service up to Donaldsonville, fifteen miles to the north, taking older black children to St. Catherine High School, where nine nuns, all black, taught them. Tuition was 25 cents per week, which was hard for Mamo and Papo to pay.

But they wouldn’t dream of depriving their sons of a Catholic education if they could possibly afford it. After all, can’t died three days before the world was born. [That’s one of Papo’s favorite sayings — RD] Even some non-Catholic black parents sent their children to study with the Black sisters, because they wanted their kids to benefit from a stricter disciplinary environment.

“When those nuns and those priests finished with your ass, they always instilled in you that you had to have something in your head,” Uncle L.C. remembers affectionately. “When we had a class reunion, none of us had been in trouble in life, and all of us had done some good. What’s the reason? It was the sisters’ school. That’s what I call Catholic school. Ain’t no Catholic schools today. You got your lay teachers, and you call it Catholic school, but it ain’t nothing like those goddamn nuns and priests, the sisters and the brothers.”

I love Uncle Lloyd. Lloyd explained to us that Father Moloney used his privilege as a white man and as a Catholic priest in a heavily Catholic area to break down barriers of injustice. He started a federal credit union to help blacks who couldn’t get loans from local banks. He started a bus service to take poor black workers to and from the Avondale Shipyards, 70 miles away, so they could get good industrial jobs, and not have to settle for low-paying farm jobs. And he worked to undermine the plantation system, which played on the ignorance of poor African Americans to cheat them. More:

In those days, blacks lived in what they called the Quarters on the various plantations’ grounds. Plantation owners would lock the gates at five o’clock, and nobody was free to come or go. No vendors were allowed onto the plantation; tenants had to buy from the plantation store. Many of them were illiterate, so they had no idea what the store was charging them. All you knew was that every month, you were going deeper into debt. If no vendors were allowed onto the property, the blacks living there would likely never learn what things were like on the outside, or what was available for them.

So Father Maloney founded a food bank. He would go by the local stores and collect canned goods and other donations, and put them in the church hall. If you needed food, you bypassed the plantation store and went to see Father. Most amazing of all, when Father Maloney saw that blacks made up 42 percent of the parish’s population, but only three were allowed to vote (the undertaker and two Baptist preachers), he organized a voter registration drive for African Americans – this, in the early 1950s, a decade or more before the civil rights movement undertook them all over the South.

The white power structure in the parish did not like that at all. They went to New Orleans to see Archbishop Joseph Rummel several times to complain about the “nigger-loving” priest. Archbishop Rummel told them to leave Father Maloney alone, that he was doing the work of God.

He was only with the African American people of Assumption Parish for four years, but Father Maloney made a huge impression on the black Catholics there, who were accustomed to a church that defended the racist status quo. He demonstrated that faith could not only give you the strength to endure hardship and injustice, but could also give you the courage to fight for a better world.

I hope you will buy Wendell’s book and read the whole thing. Unfortunately, The Wind in the Reeds tells other stories about priests being rather less than heroic, to put it mildly, on the matter of racial justice. But Wendell’s family held on to their faith — his late mother Tee was deeply faithful, even a daily communicant — because as Tee told her son, there was so much more to the Church than the priests in it.

Besides, sometimes you get priests like brave Father Maloney. It’s hard for me to imagine the guts it must have taken for a white Yankee priest to move to rural south Louisiana and challenge Jim Crow as that man did. But Uncle Lloyd told us that Father Maloney gave the black Catholics of their parish hope, because he was a harbinger of a better America to come.

The Father Maloney story is only a tiny part of The Wind in the Reeds, and it wasn’t the first thing I was planning to blog about re: the book. But the story my mom told today about the local white man in our parish who had a cross burned on his lawn simply because he said black people ought to have the right to vote brought Father Maloney to mind.