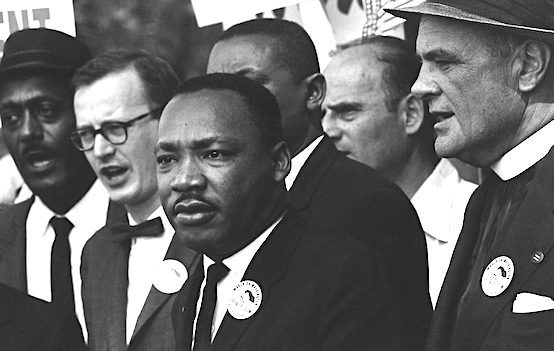

Martin Luther King, Peacemaker

After Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed by James Earl Ray on April 4, 1968 there were riots, looting, and fires in more than a dozen American cities.

The federal government called thousands of soldiers into service to keep the capitol from burning. One soldier openly manned a machine gun on Congress’s steps to keep the violence from those historic doors. Elsewhere in the country, folks weren’t so fortunate. The Justice Department’s official count after things had calmed down had 46 dead.

“King’s murder touched off a cataclysmic rampage of violence that shook the nation,” writes veteran Associated Press journalist Kathryn Johnson in her memoir My Time With the Kings. She singles out one great exception to the bloody melee: “In Atlanta that day, there was no such madness.”

Authorities were braced for it, Johnson writes, “But King’s hometown was peaceful, dignified, and respectful. Despite worries about what might happen, it was obvious to those of us covering the funeral that Atlantans, more sorrowful than angry, aimed to honor King as he had lived his life—peacefully.”

After the fires died out, that contrast—between the rage of the rioters and the control and calls for justice by those who knew King best and followed him most faithfully—helped to show the nation both what he had helped to hold back and how a better way forward was possible.

Sometimes it was even mind blowing. On the trip to retrieve King’s body from Memphis, daughter Yolanda asked if she should “hate the man who killed daddy?” “No, you shouldn’t,” King’s new widow Coretta replied, “It’s not the Christian way.”

In life, King had been a tireless advocate for change through nonviolent resistance, his own notions of racial and economic equality, and peace. In death, this outspoken black Baptist minister has become a symbol of the successes of the Civil Rights movement. That’s why the nation celebrates Martin Luther King Day on the third Monday of every January, which this year is several days after his actual birthday of January 15.

A few people have tried to debunk and demythologize King, either out of animus or because it’s hard to distill useful lessons from a symbol. However, King himself makes that a difficult task. His public leadership practically moved mountains.

King led the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott, which finally moved blacks to the front of the bus. He turned prison from something shameful into his own tool for change, reasoning with his jailers and writing that famous letter challenging the consciences of Americans.

In fact, in one of King’s few public failures, a desegregation campaign in Albany, Georgia, in 1961-62, he actually complained about the “subtle and conniving tactics” that the local powers-that-be used “to get us out of jail.”

King had a voice that moved people. In an era of prepared speeches, King instead drew on his experience with black Baptist sermonizing, that involves a lot of call-and-response back-and-forth with the crowd. Much of his most famous speech, the “I have a dream speech,” for instance, was adlibbed in response to someone from the crowd shouting at him to tell us about his dream.

And King didn’t just have a feeling he might not be long for this world—he all but prophesied it. Weeks before he was killed, King sent his wife a bouquet of plastic flowers. “Why plastic? You’ve always sent me real flowers,” she asked, quizzically. “They’re to remember me by,” he explained.

And in his last sermon, the day before his death at the young age of 39, King likened himself to Moses, saying, “I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

Perhaps that’s ultimately why King’s close followers from his hometown did not join in the rioting after this peaceful man’s violent end: because he had prepared them for it. Would that he could have done the same thing for the rest of the nation.

Jeremy Lott is the son of a Baptist minister.