Blame America Too for Our Ruptured Relations With the Chinese

BEIJING – Hanging out in China for a couple weeks is an experience. Beijing feels a lot like a Western city: tall buildings, horrid traffic, distinct neighborhoods, lots of money. You come across the full range of people—funny, friendly, officious, nervous, helpful, distant, welcoming, interesting.

Yet the political and cultural differences are also real: forced respect for political leaders (maybe everyone really loves President Xi Jinping, but, really, EVERYONE?); rigid hierarchy (for a conference opening ceremony and dinner, we “distinguished” visitors lined up like the Soviet politburo and went to our assigned seats); deference to age (I hate to admit it, but this one is an advantage now!).

There have been a lot of unofficial discussions outside of the major conference I’m currently participating in. And many topics have been of interest, including North Korea, trade, U.S. politics, and, of course, Beijing-Washington relations. While some of my Chinese colleagues are hopeful after the Trump-Xi meeting at the G-20, few have any illusions about the continuing challenge our two countries face.

Perhaps the most important question I was asked was this: why the recent worsening of relations? Or more bluntly: why do Americans hate us now? The query is worth a serious think.

Richard Nixon’s 1972 decision to break the Cold War isolation of the People’s Republic of China was long overdue. Ignoring unpleasant regimes doesn’t make them go away. The lack of communication channels with potential adversaries can have catastrophic consequences, including, among them, China’s previous entry into the Korean War.

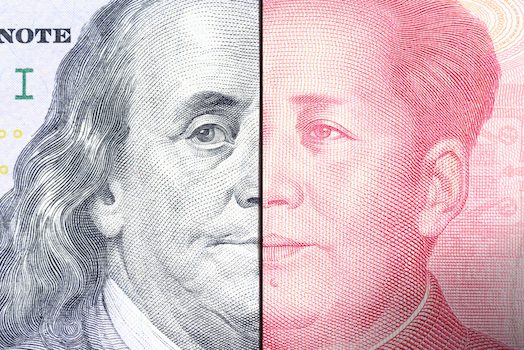

Such a state of affairs intensified hostility between the two nations, which remained until the 1970s. After Mao Zedong’s death, when China embraced reform, Americans found an avid new trading partner. Despite Beijing’s embrace of brutal authoritarianism in Tiananmen Square, many U.S. policymakers and analysts imagined that the PRC’s submersion in the international economic system would encourage social, cultural, and ultimately political liberalization. Frankly, I was among those who hoped to see such a transformation. Some Americans even imagined that capitalism would turn China into an Americanized version of itself—friendly and free.

For a time, liberalization appeared to be a reality. The PRC was no democracy, to be sure, but American culture suffused Chinese life, especially that of the young. Social strictures of the Maoist era disappeared: people were free to marry without official approval. Religious liberty advanced, irregularly and inconsistently, yes, but spaces still opened for people of faith. A genuine private sector arose, with Chinese free to seek employment where and how they wished. Even increasing indirect political debate appeared possible, as restrictions over academic cooperation, NGO activities, and foreign contacts eased. There remained red lines, to be sure, but China’s authoritarianism seemed a bit looser, more tired and less determined.

U.S.-China relations still hit significant bumps over the intervening years. The PRC was not smoothly becoming a Sinicized version of America (whatever that might even look like) because the Chinese Communist Party sat uncomfortably atop an ancient civilization. Chinese worldwide are loyal to that heritage, if not necessarily to the particular government in power. Nevertheless, with economics serving as the relationship’s foundation, the common expectation was that ties between China and the United States were destined to improve, however irregularly.

The rise of President Xi Jinping changed everything.

Of course, Xi is not alone. He represents viewpoints that have long been present within the CCP. But his government has formalized several important trends and is creating a very different China than the one once expected by Americans. The impact on American opinion has been dramatic: an increasing number of analysts express regret at having engaged the PRC economically and speak darkly of the possibility of a new cold war, this time with China rather than Russia.

In almost every area, Americans perceive a mix of double-cross and disappointment. For instance, human rights have moved in reverse: the Xi government is attempting to Sinicize religion, limit academic exchanges, tighten internet controls, and restrict NGOs. Even more shocking has been the detention of a million Uighurs in re-education camps.

The CCP appears to be turning to technology to create a totalitarian state, with pervasive cameras and a highly intrusive “social credit” system. Official attacks on the rule of law and support for enhanced party control have shattered any illusion of a move toward Western standards. Beijing’s foreign policy has grown more aggressive, especially involving territorial disputes in East Asian waters and with Taiwan. China’s military build-up has put hard power behind more political objectives. The ongoing crackdown in Hong Kong, though seen as a domestic question in Beijing, is viewed as a repudiation of the international agreement reached with the United Kingdom over the territory’s return to the PRC.

Finally, promises of further economic reforms have gone a-glimmering. Even corporate America, long the strongest supporter of the Sino-American relationship, has grown frustrated, viewing the Chinese market as almost irredeemably biased against foreign firms. Concern, even anger, has grown over IP theft and technology transfer, as well as potential security threats arising from Chinese economic activities. The result has been to dissolve what once was the firmest foundation for ties between the two countries.

Obviously, Chinese officials defend their conduct, and in some ways the PRC is only mimicking the behavior of the rising American republic of the 19th century—one can hardly be more aggressive internationally than to launch a war against a neighbor and seize half of its territory, as America did to Mexico. Nevertheless, in other areas, such as human rights, Beijing’s behavior transgresses deeply held American values.

What has driven the bilateral relationship to its current depths? The answer is a confluence of factors that in virtually every area are moving ties backwards. Moreover, there looks to be little hope for improvement. Xi appears determined to rule for life. He is committed to expanding pervasive party control over Chinese society and his international posture looks to be permanently aggressive.

The case against China appears to be a lengthy one. But U.S. policymakers need to take a more hard-headed approach that realistically assesses both the practical impact of Chinese behavior and the likelihood of changing the PRC’s policies.

First, international relations will always be messy, pragmatic, and unsatisfying. Washington must deal with many unpleasant, even murderous governments. Further, global social engineering is but a dangerous fantasy: the world’s greatest power has proven incapable even of replacing the hostile government of a small island almost within sight of its coast. These challenges and limitations are even greater when applied to a putative great power, such as China.

Second, Beijing poses no existential threat to America. The geopolitical struggle is over Washington’s continued domination of East Asia along China’s border. That will grow ever more difficult and will not be worth the cost and risk. The PRC is already a great power and, though it faces a multitude of economic and political challenges, is likely to become a superpower. The United States will have no choice but to accommodate this more powerful China, leaving friendly Asian states to take over responsibility for constraining, if not containing, Chinese behavior.

Third, Americans should not hesitate to promote our principles and values, especially involving basic human rights. But policymakers must be realistic about their ability to influence China’s development. No combination of lectures, sanctions, and threats is likely to force a nationalistic regime to abandon policies that it views as essential for its political control. Closing off contacts—canceling the visas of Chinese academics, for instance—is self-defeating. Western friends of China should look for ways to encourage increased information flows to the Chinese people while remaining engaged with the PRC.

Fourth, trade benefits both parties and is best kept free rather than excessively managed. Washington must decide what issues are broadly essential to our commercial relationship, especially given legitimate security concerns. No time should be wasted on trade balances and deficits, which are but aggregations of a multitude of private transactions. U.S. officials cannot expect to prevent Beijing from asserting government control over their economy: after all, Washington is neither advocate nor practitioner of laissez-faire. In short, what are the necessary few red lines for both states?

Fifth, Americans must give up unrealistic expectations. China will always be China—sometimes more friendly towards America and sometimes less. Moreover, U.S. policy should reflect the fact that circumstances and responses will change in the coming years. If one thing is unlikely to be static, it is China’s development.

Of course, Beijing will also have to accommodate American views and policies, so neither side is likely to be happy in making such compromises. But this is how it works now: the unipolar world is gone and won’t be seen again for a very long time, if ever.

It is easy to blame the Xi government for the ongoing deterioration of U.S.-China relations. However, American expectations and objectives have also played an important role. Both countries have a powerful, indeed even overriding incentive to avoid a rupture. Washington and Beijing should thus work cooperatively in the coming decades.

Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute and a former special assistant to President Ronald Reagan. He is the author of Foreign Follies: America’s New Global Empire.

Comments