The Imperialistic Sohrab Ahmari

For months now, we’ve been told that so-called fusionist conservatism—the synthesis of traditional Christianity and individual liberty—is dead. In its place is arising something more muscular, more direct, unafraid to harness the power of government to achieve good ends. At the furthest reaches of this new school are those like Sohrab Ahmari, who recommend a bracing dose of Catholic morality delivered unabashedly by the state. The goal is no longer to defend the boundaries of the public square but, as Ahmari puts it, to “fight the culture war with the aim of defeating the enemy and enjoying the spoils in the form of a public square reordered to the common good and ultimately the Highest Good.”

He couldn’t even win a debate. Last week, at the Catholic University of America, Ahmari sat down with National Review scribe David French, a fusionist conservative, and was thoroughly trounced. He was unable to defend his most basic positions; matters of constitutional law stumped him. Asked by French what he would actually do to make America more moral, he recommended hauling the “head of the Modern Library Association,” which doesn’t exist, before a committee of Senators Josh Hawley, Ted Cruz, and Tom Cotton, which also doesn’t exist. The row between these two began when Ahmari accused French of being insufficiently outraged over drag queen reading hours at local libraries. Yet by the end of Ahmari’s performance, even the most ardent social conservative had to be hoping a gay pride float would crash through the debate room wall.

Ahmari has a habit of being uncharitable to articles published on this website, and being a hardened TAC integralist myself, I’m forced now to draw my sword in defense. Because, really. I mean, really. Conservative commentary is more robust and energetic than it’s been at any point since the 1960s, yet we’re sitting here quarreling over whether a Catholic Church that can’t even govern itself should inform the governance of a country only one fifth of whose population is Catholic and of that only some of which actually practice. This is hoppingly, eye-wateringly idiotic, which is why it thrives on Twitter and explodes on contact with real life. That some of the commentary is trending in this direction should embarrass those of us who are Catholic.

Let’s first be clear what we’re not talking about here. This has nothing to do with thoughtful conservatives who want to use antitrust to break up Google or desire a federal ban on abortion or think the government should slap tariffs on Chinese goods. It has nothing to do with whether nationalism is a salutary force in politics or whether the Trump era will turn out well. It also has nothing to do with the fatuous old question of whether we should “legislate morality” (of course we should; are we to legislate sociopathy?). The contention at the heart of Ahmarism is that the government ought to impose a putatively Catholic conception of the common good unchecked by notions of individual liberty and so-called “proceduralism” (which the rest of the planet calls “the rule of law”).

The enemies of Ahmarism, then, are libertarianism with its emphasis on personal freedom, classical liberalism with its rules of governance, and progressivism with its debauched social ethic. These things the Ahmarists roll up into a ball and term “liberalism,” which they then inveigh against in columns that at first were interesting but now sound heavily mad-libbed. As with all ideologues, they refuse to recognize distinctions—between ordered political liberty and unlimited license, for example. As with all fanatics, they blame the enemy for all that’s gone wrong and credit him for nothing that’s gone right. (This is not, I should point out here, a critique of Patrick Deneen, whose Why Liberalism Failed is more a warning of what’s to come than a theocratic alternative. A conversation between Deneen and French would have been genuinely interesting.)

Ahmari’s politics is the sort held primarily by adolescents. It divides the world into easy categories, one strong (Ahmarists), another compromising (liberals), and a third evil (leftists)—and is there really such a difference between those last two at the end of the day? It’s the speech at the end of Team America rinsed in holy water. But let’s take it seriously for a moment. We’re still left with the question of what exactly it intends to do beyond the weak (and notably classically liberal) panacea of an elected senator haranguing the head of a voluntary organization. It’s been months since the Ahmarists planted their flag atop the conservative movement. What specifically do they want? How will they shape culture and public opinion in favor of it? How will they sell a minority-view collectivism to a country of which the historian Robert Wiebe rightly said, “There has never been an American democracy without its powerful strand of individualism, and nothing suggests there will ever be”?

Even if we assume for the sake of argument that they can do all that, we’re still left with the question of efficacy. The past two decades have not exactly been a credit to government power. The feds horrifically botched the Iraq war, unleashing chaos throughout the Middle East. Obamacare failed to relieve high premiums and sent deductibles soaring. Two major education reforms have scarcely budged test scores. Even smaller and less remembered measures, like Cash for Clunkers, didn’t work the way they were intended. Why should Ahmarist social engineering turn out any better? How will they get around the old objection that government workers tend to pursue their own ends rather than the common good? How will all this be paid for, given that entitlements are set to submerge the federal budget and the national debt stands at $22.5 trillion?

And what if, as so many collectivisms have, it all goes horrifically awry?

Some of those questions—saints preserve us!—involve procedure, yet they’re the sort you have to answer if you want to step into the political arena. And many of them have theological origins, or at least implications. Earlier this week, TAC ran an essay that had the audacity to point out that Protestants exist and some of them may be hesitant to sign on with a Catholic theocracy. Ahmari’s response on Twitter was telling: he mocked those Protestants and caricatured them as hicks. That ought to be all the proof you need that, as with so many radical reform efforts, this isn’t about the working class—they’re expendable the second they go against the agenda. Ahmari is, as Burke put it, one “of those democratists who, when they are not on their guard, treat the humbler part of the community with the greatest contempt, whilst, at the same time, they pretend to make them the depositories of all power.”

What this is really about is cultural imperialism, taking America as it is and replacing it with something it’s never been. Thus do we get Ahmari on Twitter saying—quote—“Part of our work is recovering the Hispano-Catholic founding of America, which, as a priest friend reminded me tonight, enjoyed a much wider geographic sphere and cultural span than the second, Anglo Founding.” (Did he just triangulate his way to open borders?) It may be that Ahmari, having supported much of the imperialistic neoconservative foreign policy, is the perfect representative for this new imperialism at home: both require the state to impose that which it cannot impose and to transform that which it cannot transform. This is true even of Ahmarism’s more modest proposals. A drag queen reading banned at a public library will simply move to a private building—and then what?

The root problem in America today, as the Ahmarists see it, is radical atomization, and rightly so. We are too individualistic, too disconnected from our civic institutions, too quick to abandon the places where we grew up, too eager to pop in our ear buds and tune out the world. But there is no pro-atomization party, no “divide or die!” chants ringing down Constitution Avenue. The argument, at least on the right, isn’t over whether the problem exists; it’s over whether the federal government can and should put the pieces back together. The classically liberal side gets too bogged down in legal talk, elevating constitutional clauses to the level of eternal truths. That can make them sound inadequate, as French sometimes does. But they also raise worthy objections about the clumsiness of state action and the tendency of government to corrupt. Shouldn’t we think about the reasons they were erected before tearing down the fences of “liberalism”? The Ahmarists have only caricature: their opponents are hoary libertarian relativists and that’s that.

Ultimately this is all a tedious waste of time. There’s never going to be a Tweed Revolution—a bunch of trads storming the Capitol building, waving their bubble pipes around, having bored the guards to death with their tweets about the Mortara case. (See? I can caricature too.) If we do manage to solve the problems of today, it will be through the old-fashioned, unexciting, fundamentally American method: voluntary action by normal people, most of whom aren’t on Twitter, in full understanding that there are no shortcuts to cultural change, backed by some reasonable and mostly financial help from the government. Ahmari can’t see anything useful between the facile extremes he’s constructed. But it’s there and we should encourage it.

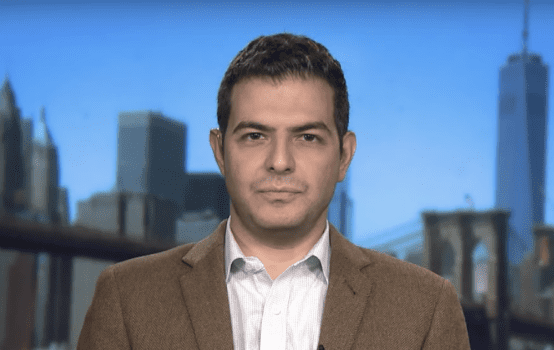

Matt Purple is the managing editor of The American Conservative.