The End-of-History Smart Set

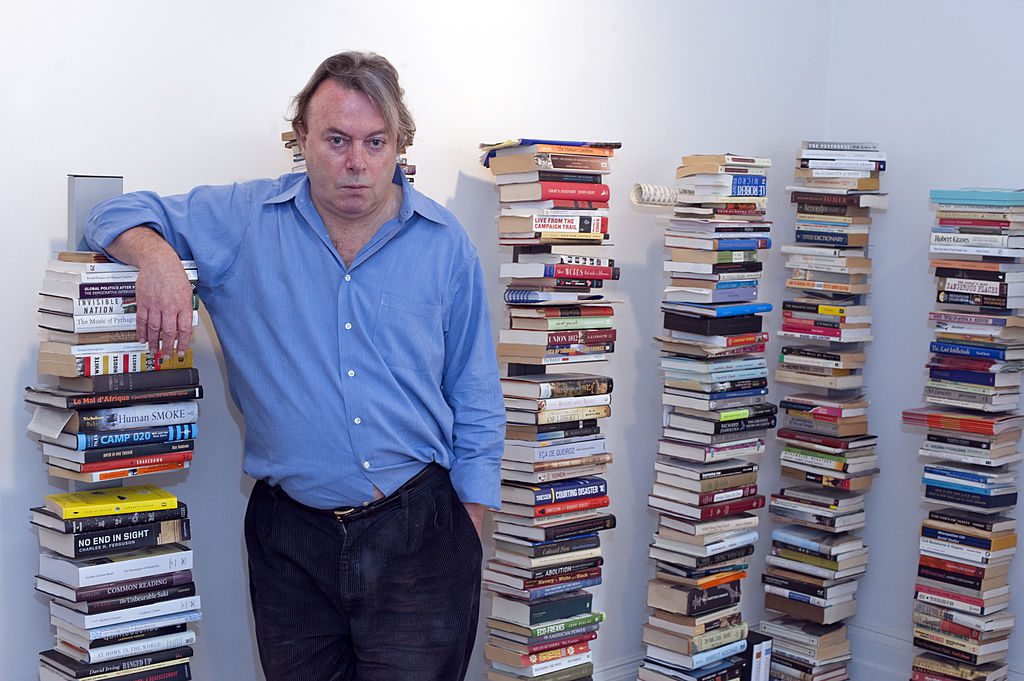

Sound the knell: The public intellectual is dead. His intellect has been narrowed by specialization, while his place in the public square has been crowded out by Twitter edgelords and Clubhouse grandstanders. And away with him too has gone something else, the literary set, those clubby packs of writers who once defined their nations’ arts and letters over boozy lunches-cum-dinners-cum-self-hagiography-scenes. The last of these was a clique of British intellectuals that TAC contributor Ben Sixsmith dubbed the Loomers. They were Christopher Hitchens, Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie, and, as Hitchens would have readily told you, many, many more comrades and friends.

Sixsmith coined the “Loomer” label both because these men were Baby Boomers and because they loomed over British intellectual life for decades (and in some ways still do). His assessment is mostly a disapproving one. The Loomers, he thinks, represented the triumph of literary style over substance, and within style the prioritization of cleverness over power. I don’t wholly agree—McEwan, at least, is an elegant and precise stylist—but I do think the Loomers are worth examining for another reason, one that Sixsmith also touches on: their politics.

The Loomers—I’m going to culturally appropriate Sixsmith’s term if only because no one else has ever come up with a better one—captured a political tendency that, as recently as 15 years ago, seemed unstoppably ascendant. It would be unfair to call them “neoliberals,” a word whose meaning has been almost wholly devalued in any case. But they did come to represent, stylishly and often unsparingly, a kind of center-left establishment consensus at what was supposed to be history’s end. That viewpoint has since faded and may never return to its former prominence.

The first thing to know about the Loomers is that they were all either atheists or agnostics (and there is a difference, stressed Amis, who thought atheism could be too premature and “lenten”). Hitchens, late in life, wrote a book subtly titled God is Not Great and spent much of his time sparring across lecterns with clerics and imams. Rushdie was famously the subject of a fatwa by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini, which forced him into hiding and resulted in several assassination attempts against him and his translators. Hitchens in particular viewed both this kill order and the attacks of 9/11 as clarifying moments, when the free and secular world was brought into inexorable conflict with the backward hordes of theocratic unenlightenment.

This opposition to jihadism had been a long time in the making. The Loomers were products of the 20th century, born into the early Cold War, present at the fires of 1968 and then the headachy aftermath. The villains of that time were mostly authoritarian bullies: glowering and pudge-nosed Soviet officers, fascist strongmen in mirrored sunglasses, po-faced followers of Mao and Pol Pot, junta fighters pocketing CIA money in humid jungles, baton-swinging police officers unleashed on their own citizens. Whereas the heroes were Orwell, Koestler, Auden, those opposed to fascism who also recognized that the USSR was no corrective.

The Loomers began as ’60s radicals and never renounced their leftism. But they did eventually put down roots in this more liberal and anti-totalitarian soil. This led them to reject a particular segment of the left, one that clung to the revolutionary dream and made excuses for Soviet and third-world atrocities. They retained the internationalist outlook of Marxists but did away with much of the “workers unite!” class struggle stuff that had so animated the earlier left. They sought the liberation of the world’s peoples not so much from capital as from oppressors in general, whether communists or fascists or theocrats.

If that sounds like it could end up dovetailing with George W. Bush’s crusade to spread democracy around the world, that’s because it did. Hitchens became one of the most ardent defenders of the disastrous Iraq war, which he viewed as an opportunity to topple a brutal regime. Clive James, another Loomer, agreed. McEwan, though he opposed the war, is often accused of being compatible with Tony Blair.

The Loomers also made their peace with capitalism—Hitchens took to calling it “the only revolution in town”—though only to a point. Martin Amis’ best novel, Money, is a coruscating indictment of Western greed and often read as a satire of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain. None of the Loomers ever became anything like Randians or supply-siders. And therein one of their charms: For all their inveighing against stuffy old orthodoxies, they were still grounded in a very particular English traditionalism. Read McEwan’s novel Atonement and you occasionally catch Jane Austen peeking through the pages, even as the book wrangles with more modern themes. Hitchens was an admirer of Evelyn Waugh and G.K. Chesterton, and while he detested their politics and religious faith, he was surely attracted to more than just their sentence construction.

Yet whatever blend of conservatism and radicalism might have fermented in the Loomer jar, they’ve since ceased to come off as anything other than liberal elites. Two episodes illustrate this well. The first involves McEwan’s novel Solar, about a physicist fighting climate change who has a calamitous personal life. It’s not his best work and was poorly received in the United States for reasons that are complex (it’s the kind of pitch-black comedy we Americans sometimes find perplexing; also it’s just not that good). But according to McEwan, this transatlantic disconnect was simple. Americans, he sniffed, are “profoundly bored” by climate change. The rubes. The second episode also involves McEwan and his one-man crusade against Brexit. “Let’s stop pretending that there are two sides to this argument,” he demanded. “There aren’t.”

The Loomers, even when they were marching and pumping their fists, were always elites of a sort, products of prestigious English schools with posh accents. Yet as the 20th century progressed, they were elevated into another upper echelon: the political establishment. Their ideas won out. Liberalism triumphed over collectivism, open societies prevailed over closed, secularism shoved aside even the most watered-down religion. The backlash against the ignorance and authoritarianism that had done so much damage during the preceding decades calcified into a new liberal consensus. The cause célèbre became climate change, which conveniently turned scientific progress and international cooperation, major liberal priorities, into matters of planetary survival.

The Loomer program had always been first and foremost about liberation, from fascism and communism, but also from stuffy churches, creaking traditions, benighted myths, gray provincialism, iron-fisted nationalism, family values, sexual morality. With the new liberal consensus, this found broad acceptance. Yet there was a myopia at work. What never seemed to get asked was whether we could be liberated from all this, whether fresh tyrannies might yet arise out of secularism and scientism, whether some (though certainly not all) of those bonds ought not be broken.

Yet on the liberating went. It ultimately culminated in the final Loomer cause, the New Atheism movement of the late 2000s. Here was a struggle to liberate man from nothing less than God himself. Hitchens became one of the most recognizable New Atheists, lending them much of their polemical punch. He was always the most political and interesting of the Loomers, a raconteur and tough debater with a refreshing appetite for both literature and alcohol. He was a gateway intellectual—read him and you twitched to read more, to take up the other authors he dropped so effortlessly throughout his own work. Yet study him long enough and you realized his views were deceptively simple. The Enlightenment must triumph. Science and discovery are good. Religion and barbarism not at all. Fight them however possible, including if necessary through an undeclared air war.

But what happens if science brings into the world something like the internet, which at present seems to be hurtling our politics back to the Dark Ages? What if out of the vast liberal frontier comes a new hunger for illiberal order? What if people start to yearn for those old bonds that have since been snapped away? Sixsmith notes that the Loomers “have had almost nothing to say about social stratification, consumerism, gender, mass migration and the Internet.” That’s because those issues, brought to the forefront during the new century, can’t necessarily be addressed through that old liberal binary.

Still, let’s allow that it works both ways. Those moderns who now rail against liberalism are also due for a reckoning with the Loomers. Because the main lesson from across the blood-blackened 20th century is this: the individual can never be made wholly subordinate to his government. There’s no such thing as the abstract and philosophical state; in the real world, ruling classes are made up only of people, as fallen and flawed as the rest of us. To make citizens the property of the state is thus to make them the slaves of others, with all the abuse that invariably follows and with any kind of worthwhile civilization ultimately foreclosed upon.

This was the fatal error made by all the worst regimes of the fighting 20th. It’s a reason liberation became such an attractive idea and gave way to the liberal order, however skewed it’s since become. And at their best, the anti-totalitarian Loomers tried to make sure we didn’t forget it. As the protagonist sums up in Ian McEwan’s novel Sweet Tooth:

T.H. Haley owed nothing to a world that nurtured him kindly, liberally educated him for free, sent him to no wars, brought him to manhood without scary rituals or famine or fear of vengeful gods, embraced him with a handsome pension in his twenties and placed no limits on his freedom of expression. This was an easy nihilism that never doubted that all we had made was rotten, never thought to pose alternatives, never derived hope from friendship, love, free markets, industry, technology, trade and all the arts and sciences.

Sound familiar? It will if you’ve been on Twitter lately. Gratitude for our prior gains isn’t going to cool our tempers or heal our anomie. But to shed it entirely, to forget the lessons of the previous century while attacking the problems of our own, would be suicidally foolish.

Comments