Roger Stone’s Deal Is Chickenfeed Compared to Petraeus and Berger

Howls of outrage erupted among members of America’s political and media elites when President Trump commuted the prison sentence of his onetime political associate Roger Stone on Friday.

Even though Trump let Stone’s felony conviction stand, he criticized both the decision to prosecute and the sentence handed down as unjust. To Trump and most of his followers, Stone’s plight was just the latest travesty arising from Robert Mueller’s probe into the “Russia collusion” allegations.

To the president’s critics, though, sparing Stone from serving time in prison was more evidence of Trump’s abuse of power and contempt for America’s constitutional system. The ever-helpful Washington Post even noted that in making the decision about Stone, the White House bypassed more than 13,000 other federal inmates who were seeking pardons or commutations. The implication was obvious: this was a corrupt payoff to a political crony involved in the Russia collusion plot.

Trump’s intervention is certainly controversial, and it suggests favoritism to an administration loyalist. But it is hardly the worst case in which a very different, far more lenient, standard of justice existed with respect to a powerful, politically connected figure in the foreign policy arena. Two other examples stand out as especially egregious: the sweetheart deals given to Bill Clinton’s former national security adviser, Samuel R “Sandy” Berger, and former CIA director David Petraeus.

After leaving the Clinton administration, Berger served as a top foreign policy adviser to Sen. John Kerry (D-MA) during Kerry’s 2004 run for president. Indeed, Berger was widely thought to be on Kerry’s short list to become secretary of state. But evidence emerged during the campaign that in 2000 Berger had illegally removed classified documents on two separate occasions from the National Archives—reportedly by stuffing them down his pants before exiting a secure reading room. The following year, after months of negotiations with federal prosecutors, he entered a guilty plea to a misdemeanor charge of mishandling classified material. It was, to put it mildly, an extremely generous offer by the government. Berger’s theft of highly classified materials was brazen, and worse, evidence emerged that he did not merely steal the documents, he destroyed three of them—all, according to his testimony, copies rather than originals.

Treating such violations of law as a mere misdemeanor was the essence of a sweetheart deal. But the penalty phase of the plea bargain was even worse. Not only did Berger avoid having to serve any jail time, the penalties he did experience barely amounted to a slap on the wrist. He paid a $50,000 fine and relinquished his security clearance for three years. The court also sentenced him to 100 hours of community service. Someone with Berger’s economic status probably could pay $50,000 out of the family’s petty cash account. And losing access to classified material for only three years instead of permanently was an insult to every government employee who had honored the rules connected with such access.

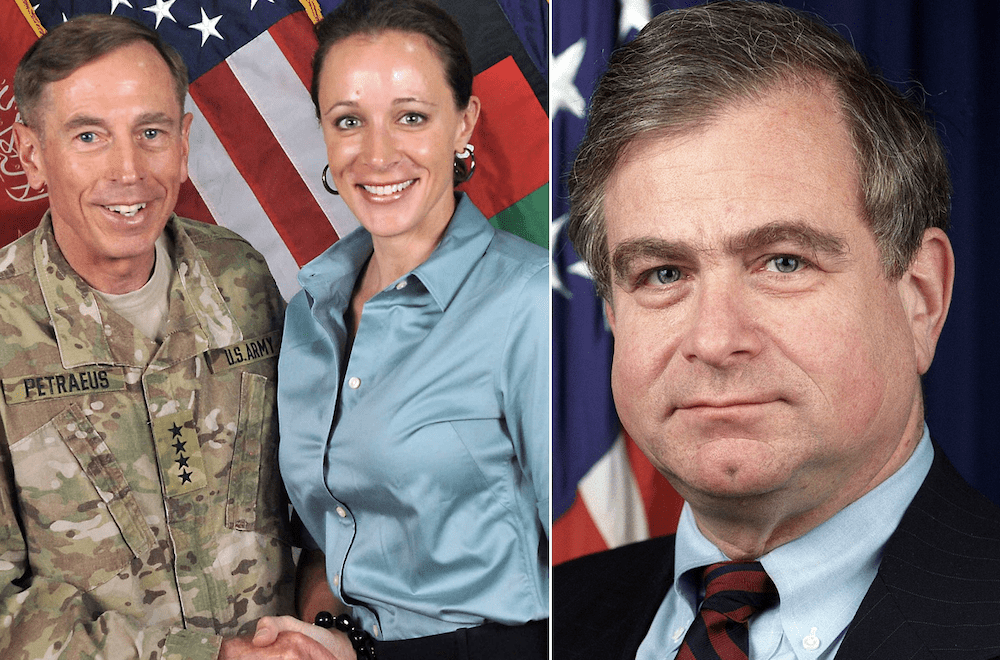

The Petraeus case appeared to be an even clearer example of the Washington establishment protecting one of its own. His criminal conduct occurred when he served as the commander of U.S. military forces in Afghanistan, although it did not come to light until later when he was head of the CIA during the Obama administration. After a lengthy FBI investigation, Petraeus admitted that he gave highly-classified journals to his lover, Paula Broadwell, who was writing his biography. The journals contained extremely sensitive information about the identities of covert officers, military strategy in the Afghan theater, intelligence capabilities and even discussions Petraeus had with senior government officials, up to and including President Obama. Petraeus also admitted that he had lied to FBI and CIA investigators about his conduct when first questioned.

Despite such misconduct, he only had to plead guilty to a single misdemeanor charge of unauthorized removal and retention of classified information. Although, theoretically, the penalty for even that violation could be a year in jail, as part of the plea bargain, the general would not have to serve a single day behind bars. His sentence consisted of two years’ probation and a $100,000 fine. Although the latter might seem to be a significant financial penalty, it is reportedly less than Petraeus charges for a single speaking engagement.

It was another example of a flagrant double standard that benefited a prominent member of Washington’s military and foreign policy establishment. The Intercept’s Peter Maass fumed that the deal confirmed “a two-tier justice system in which senior officials are slapped on the wrist for serious violations while lesser officials are harshly prosecuted for relatively minor infractions.”

There is ample evidence of such a double standard. Maass noted that a year earlier Stephen Kim, a former State Department official, pled guilty to one count of violating the 1917 Espionage Act for merely discussing a classified report about North Korea with Fox News reporter James Rosen. Maass emphasized that Kim did not hand over a copy of the report, he merely discussed it. Moreover, the report itself “was subsequently described in court documents as a ‘nothing burger’ in terms of its sensitivity.” Yet, even with the plea deal, Kim was given a 13 month sentence in federal prison. CIA agent John Kiriakou, who confirmed the name of a CIA agent to a reporter in the course of blowing the whistle on U.S. government abuses (the reporter never published it), received an even longer sentence—30 months in prison, and he did his time. The double standard at play could scarcely be more blatant.

Another striking feature of the Berger and Petraeus episodes was the meager media outrage about such miscarriages of justice. A handful of critics spoke out against the extraordinarily mild treatment of Petraeus, but it was a very small contingent. Even supposedly critical articles in the mainstream press seemed to go out of their way to send a mixed message. A Washington Post article on the general’s guilty plea contended that Petraeus was “considered one of the greatest military minds of his generation.” Indeed, that comment was in the piece’s opening sentence. Similarly, the first words in the ABC News account of the guilty plea were “Decorated war veteran….” The Miami Herald referred to the conviction as a “humbling chapter of an exemplary career.”

Such comments stand in stark contrast to the vitriol the journalistic community is directing at Trump’s decision to keep Roger Stone out of prison. Stone’s case does warrant serious concerns about how Washington insiders benefit from their high-level political connections even when they violate the law. But the questionable aroma arising from this new incident is mild compared to the stench associated with the Berger and Petraeus episodes and the mainstream media’s hypocritical treatment of them.

Ted Galen Carpenter, a senior fellow in security studies at the Cato Institute and a contributing editor at The American Conservative, is the author of more than 850 articles as well as 12 books, including The Captive Press: Foreign Policy Crises and the First Amendment (1995).

Comments