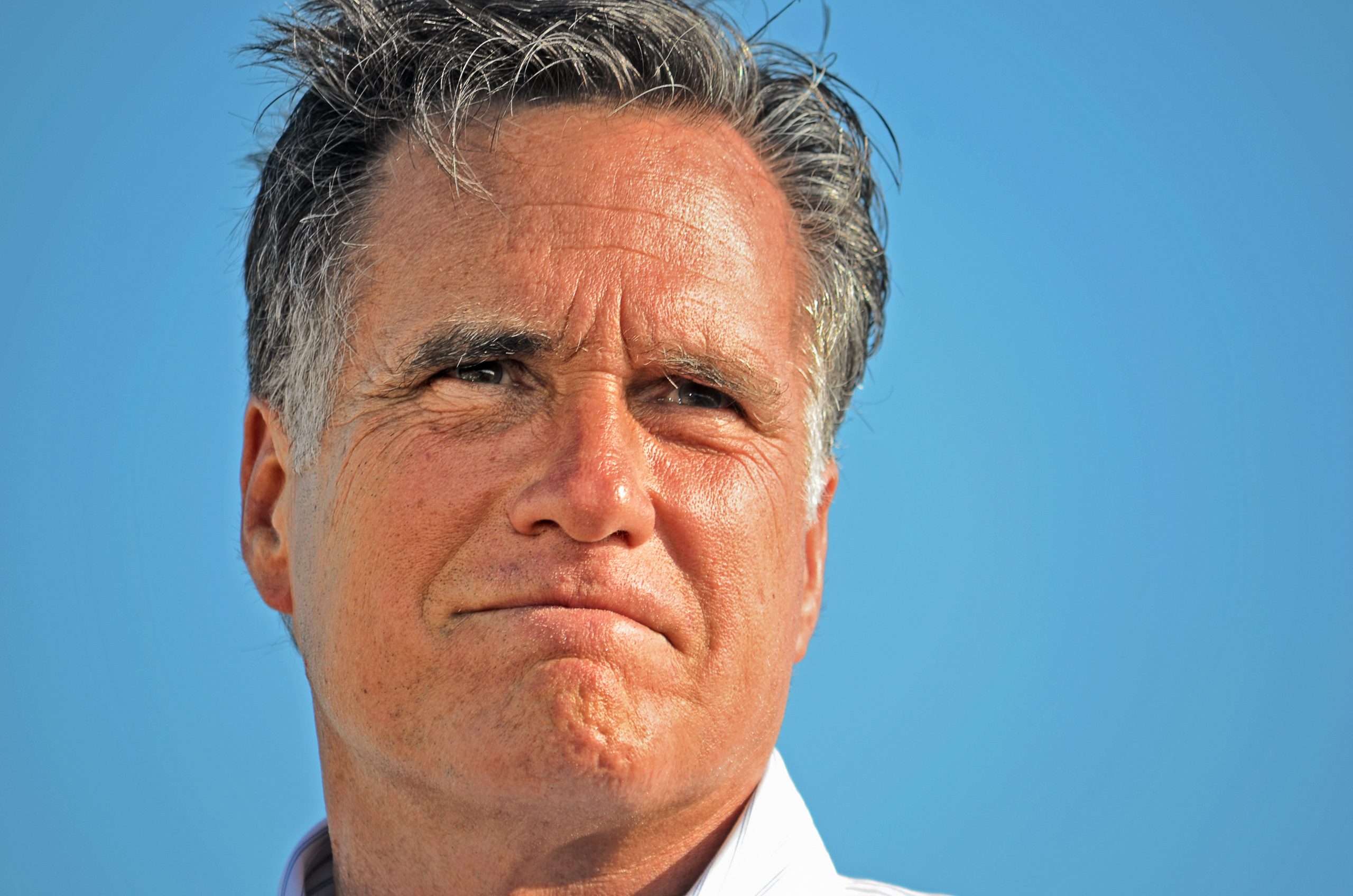

Romney Says America’s Leadership is Too Old to Take on China

“There is no way that a bunch of men and women in Congress are going to come up with a strategy to confront that,” Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) said bluntly on Wednesday. “We are being outcompeted in a dramatic way on the world stage.”

Speaking to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the 2012 GOP presidential nominee said the Chinese regime has an “extraordinarily comprehensive strategy” for world power. “We’re not equipped as a group of folks that are a little long of tooth to come up with something so comprehensive that we’re going to push back in a positive way,” he said. “And so I wonder, what do we do?” Romney said.

Presumably, somebody in Washington should be on this.

The veteran Irish financial journalist Eamonn Fingleton had a sharp piece in the current print edition The American Conservative grappling with that question. It was published online Thursday. “The mantra became ‘trade deficits don’t matter,’” Fingleton writes of intellectual debates of decades past. “This served the interests of such mercantilist nations as Japan, Germany, and China, which have continued avidly to build ever more advanced manufacturing industries and thus have generally gained mightily from the offshoring of American jobs. Because the major mercantilist nations are now by far the world’s most prolific sources of investment capital, Wall Street panders to their every need.”

“Almost no one in the American press has questioned this,” Fingleton continues (of course, TAC has long been a notable exception). “Since the ‘sophisticated’ view among media professionals has become that the United States is leading the world into a new post-industrial era of unprecedented prosperity. In the meantime, supposedly, the faster U.S. factories are shuttered, the better.”

In what could be a response to Romney’s query, Fingleton suggests to America’s new president: “The model for what Biden should do is already out there: the Nixon Shock package of 1971,” a tariff policy that Fingleton makes the case allowed the U.S. of A to remain “the 800-pound gorilla of the world economy.” And where does the gorilla sit? “Anywhere he likes.” Wrapping up, Fingleton says, chillingly: “Any measures Biden takes now will necessarily be four decades too late. The scale of the problem he faces is colossal. But if he doesn’t act promptly and with considerable resolution, it is hard to see how the United States can aspire to a continuing future as a First World power.”

It is not at all clear if Romney would ever read someone like Fingleton, who is a pedigreed and respected thinker, but also a clear outcast of his generation. The two men were born a year apart, so while Fingleton was inveighing against what became the reigning approach for an age of globalization, Romney was in some ways steering the ship, a captain of (the financial) industry, a pioneering private equities equite, some would say an outsourcer par excellence, and later, as a major party nominee for president, chief complainer that Barack Obama wasn’t trade-happy enough.

Yet, for all that’s known about Romney, so much remains obscured. His worldview would seem quasi-modo, even in his eighth decade, curious. “And so I wonder, what do we do?” is not something you hear a senator confess every day, that is revealing ignorance, especially on matters of state and strategy against America’s staunchest rival yet.

Staffers who have worked for him swear, “Mitt’s a realist,” not a neoconservative, as the sketches of his stillborn administration once implied. His network of devotees remains influential, from the Republican fixer and radio host Hugh Hewitt to Robert C. O’Brien, the former national security advisor. Indeed, in conservative circles, the now-junior senator from Utah is occasionally bandied about as a sort of proto-Trump.

It was Romney, back in the day, who was the favorite of hardliners like columnist Ann Coulter and blogger extraordinaire Matt Drudge, favoring tough-minded immigration policy. And it was Romney who sounded early alarm bells on China, and has continued to, something that became relevant again as Romney was considered to be Donald Trump’s secretary of State, and is now back in the saddle in Washington. Saurabh Sharma of the zoomer-nationalist American Moment has given what he calls his “qualified case for Mitt Romney” and Oren Cass, the executive director of American Compass, which seeks to build on some of Trump’s ideas though not Trump the man, is a former top Romney staffer.

So, Romney’s present position seems an uneasy one, that is, as the paragon of the conservative old guard. Though to be sure, Romney has espoused picayune views like Russia is America’s greatest geopolitical adversary (Obama was right the first time) that would fit like a glove at the American Enterprise Institute, the once-peerless conservative think tank.

But the shroud of pro-Trump vs. anti-Trump obscures more than it reveals.

Romney was once a political independent and proudly so. “I was an independent during Reagan-Bush,” Romney told Sen. Ted Kennedy during a 1994 Senate debate in Massachusetts. And pro-lifers, of course, long viewed Romney with deep suspicion, as the once-avowedly pro-choice governor of the Bay State, which potentially cost him the 2012 election as he curried only tepid white evangelical support—that’s debated, however, both on the merits and on the contention that given later enthusiasm for Trump, anti-Romney suspicions in that corner were always rooted in mere bigotry.

But even on this score, Romney was and remains the Republican Rorschach test. The number of social conservatives who quibble with how he comports his personal life, as a devoted (sprawling) family man, husband, and teetotaler, is exactly zero. The man is seemingly a parody of Protestant work ethic. And perhaps it is that very optimism and structure that led him to misread, and become befuddled, by a fading America.

“I think the most pessimistic candidate is going to win,” entrepreneur Peter Thiel advised Romney in 2012, as first reported by George Packer in his book, The Unwinding.

Four years later, a much different businessman and Republican took the advice and won the contest that Romney couldn’t. And four years after that, Donald Trump is gone from Washington, and it is Romney that remains. Perhaps speaking to the paucity of dynamic figures in the upper chamber (anyone heard from Martin Heinrich, senior senator from New Mexico, ever?), Romney is in the cadre of the top ten, if not the top five, more important senators.

But he’s apparently all ears about what exactly to do with that power. And he thinks the same of his generation.

Comments