On the Passing of Les Murray, Our Greatest Poet

I like to say that I worked with Les Murray at Australia’s Quadrant magazine. He was literary editor; I was an editorial assistant to John O’Sullivan. In fact, I never interacted with him once. You see, Murray rarely left his hometown of Bunyah, a bush borough with a population of about 150. He didn’t own a computer—he typed all his proofs on a typewriter—and we were only allowed to call him on the phone in emergencies.

So writers would mail their short stories and poems to the office in Sydney, and we’d ship them to Bunyah in a big parcel once a month. Those he chose for publication were returned to the office. The rest he sent off in their their self-addressed, stamped envelopes. The rejected manuscripts would return to their writers with the margins covered in suggestions and encouragements from the man The Atlantic called “the greatest poet alive.” Quite the consolation prize.

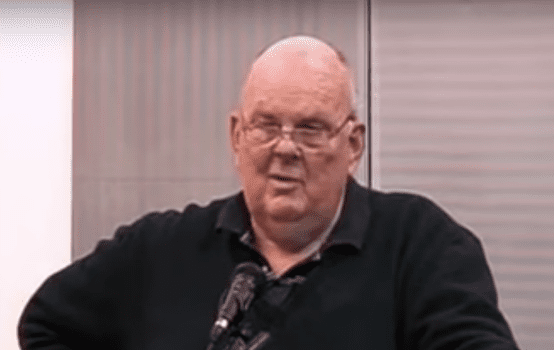

To me, that was all part of the irresistible charm of Les Murray. The morons at the Nobel Committee excepted, nobody would disagree with The Atlantic’s descriptor—certainly not since the death of Geoffrey Hill in 2016. And yet Murray wasn’t a windswept, romantic figure. He wasn’t a tweedy professorial type or a cosmopolitan in a dark turtleneck. He was a proud bumpkin and an avowed Luddite with bad teeth and a penchant for ugly sweaters. He suffered from depression, the sexiest of mental illnesses; he was also probably autistic, which is more prosaic. Never has such an extraordinary soul carried such an ordinary corpse, as Marcus might have said.

It wasn’t an affectation, either. Since T.S. Eliot, English-language poetry has been almost totally inaccessible. Hill, a disciple of Eliot, defended the difficulty of modern poetry, telling the Paris Review: “We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other.” Nevertheless, this difficulty has made poetry an elite (perhaps an elitist) hobby.

Only magnificent toffs like the Cavaliers could take pride in the amateurishness of their verse. Murray did the next best thing: he rendered plain scenes of bush life in the most exalted English an Australian has ever mustered. Take this excerpt from his magnum opus “The Invention of Pigs,” which may have arisen from a wager that he couldn’t write a moving verse about bovine genitalia:

Come our one great bushfire

pigs, sty-released, declined to quit

their pavements of gravel and shit.

Other beasts ran headlong, whipping

off with genitals pinched high.

Human mothers taught their infants creek-dipping.

Fathers galloped, gale-blown blaze stripping

grass at their heels and on by

too swift to ignite any houses.

You don’t need firsthand experience with Australian bushfires (though I have it) to hear the notes of subterranean, ancestral dread and studied, masculine nonchalance in those lines. Or this gem from “Sidere Mens Eadem Mutato”:

Some things did change. Middle class girls learned to swear

men walked on the face of the moon once the Pill had tamed her

and we entered our thirties. No protest avails against that

the horror of Time is, people don’t snap out of it.

Now student politicoes well known in our day

have grown their hair two inches and are running the country.

Revolution’s established. There will soon be degrees

conferred, with a fistshake and speech, by the Dean of Eumenides.

The degree we attained was that brilliant refraction of will

That leaves one in several minds when facing evil.

It’s still being offered. The Church of Jesus and Newman

did keep some of us balanced concerning the meaning of “human”

that greased golden term (all the rage in the demiurgy)

though each new Jerusalem tempts the weaker clergy.

Murray was a serious Catholic and he let his readers know it—he dedicated all his collections of poetry “To the Glory of God.” Like his literary co-religionists James Joyce and Gerard Manley Hopkins, Murray was obsessed with the idea of the Sacramental, and was fascinated by the Church’s belief that “a thing can be God and nature at the same time.”

That means everything we do and everywhere we are is a sacramental, a poem. “We’re not rational humans,” he said, “we’re poetic, and we take on our ideas like poems.” As he wrote in another masterpiece:

Full religion is the large poem in loving repetition;

like any poem, it must be inexhaustible and complete

with turns where we ask Now why did the poet do that?

You can’t pray a lie, said Huckleberry Finn;

you can’t poe one either. It is the same mirror:

mobile, glancing, we call it poetry,

fixed centrally, we call it a religion,

and God is the poetry caught in any religion,

caught, not imprisoned.

So it just depends what poem we choose to occupy. As for Murray: “I found in the Catholic one there was a chap who sacrificed himself rather than demanding human sacrifice.”

He didn’t want the Nobel, fearing its “devouring fame,” God bless him. He’ll be glad to meet that chap from the poem, unencumbered by that hunk of recycled gold around his neck.

“There’s always more to write,” he told the Sydney Morning Herald about a decade ago. “I haven’t written all the poems yet. And when I’m dead and gone there’ll be plenty of others who will do it.” But none like him.

Requescat in pace.

Michael Warren Davis is associate editor of the Catholic Herald. Find him at www.michaelwarrendavis.com.

Comments