Why Legislative Powers Need to Be Checked, Too

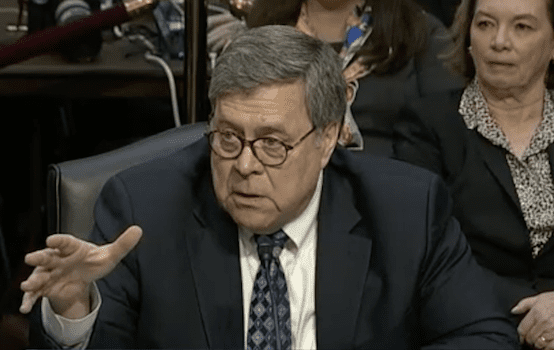

When Attorney General William Barr went before the Senate Judiciary Committee the other day to defend his handling of Robert Mueller’s report on the “Russian collusion” investigation, Hawaii’s Democratic Senator Mazie Hirono issued what struck many as a devastating accusation. “You’ve chosen to be the president’s lawyer,” she said.

That echoed a refrain heard often in the wake of the Mueller report and the effort by Democrats and media mavens to impugn Barr’s motives and actions. As Erin Dunne put it in the Washington Examiner, the attorney general “is not the president’s lawyer but the country’s.” She added, “That means that the attorney general does not defend the president but, instead, represents the country in legal matters.”

Dunne’s statement of the attorney general’s job description and Hirono’s accusatory blast represent a common vulgarity in political discourse these days—oversimplifying complex matters in order to mow down the opposition. In fact, the question of the attorney general’s proper role in such matters is not simple at all, but highly complicated, tangled, and difficult to navigate.

Charlie Savage of The New York Times captured this tangle rather well in an otherwise one-sided “news analysis” the other day. He noted the “tensions inherent in the role of the attorney general, pitting the ideal that the nation’s top law enforcement official should be independent of politics and enforce a neutral understanding of the rule of law against the reality that he or she is politically appointed and part of any administration’s team.”

The rest of Savage’s analysis didn’t explore these tensions with any particular nuance. But it might be instructive to go back to the legal crucible known as Watergate, when the notion of Justice Department independence first emerged. A good place to start would be a Newsweek column by Stewart Alsop, a leading Washington journalist of the day. President Richard Nixon, under scrutiny for his role in that wicked scandal, found himself beleaguered as few presidents had ever been. This had generated, wrote Alsop on October 8, 1973, a new political reality: “the president of the United States, for the first time in American history, has lost control of his own Justice Department, an essential instrument of Presidential authority. The President is thus no longer master in his own house.”

Alsop was not a Republican and certainly not an instinctive defender of Nixon. He was thoroughly aware of the legal thicket confronting the republic. But he was making an observation about the constitutional distribution of power and the president’s executive authority under Title II of the Constitution. As his column makes clear, no attorney general before that autumn of 1973 had ever confronted the “tensions” that Savage noted. To illustrate the point, Alsop quoted “the casual remark of a member of the Court” (presumably uttered during oral arguments): “Of course it never occurred to the framers that anything like this could happen. They naturally thought that the President would control his own Justice Department, and of course before this he always has.”

Thus, the notion that the Justice Department could be wrested from presidential control is a relatively new point of view in American constitutional thinking. And yet just 46 years later, there is for many an ironclad conviction that the attorney general should, as a matter of course, place himself above the man who gave him the job and at whose pleasure he ostensibly serves. The idea that he is beholden strictly to the American people has opened the way for Congress, claiming to be speaking for the people, to gain leverage over the executive branch.

Obviously, this conflict is fraught with constitutional difficulty. We’re not going back to the days before Watergate when many legal scholars believed the only recourse for presidential misbehavior was the Constitution’s impeachment language, in part because no one could expect the president’s own Justice Department to take any action against him. A leading constitutional scholar of the Watergate era, Yale’s Alexander Bickel, argued that Nixon had the right to fire his attorney general for any reason or no reason, even in the midst of a “special prosecutor” investigation into presidential misbehavior. By extension, under Bickel’s reasoning, he also could fire the special prosecutor. Neither the legislative branch nor the judicial branch had any say in the matter.

Just 12 days after the Alsop column appeared, Nixon brazenly embraced the Bickel interpretation and ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to fire the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox. Richardson refused. His deputy, William Ruckelshaus, also refused. As just about everyone knows, all hell broke loose. It was called the Saturday Night Massacre, and it was the beginning of the end of Nixon’s presidency.

At this point, Nixon’s state of siege was largely a matter of politics. The Saturday Night Massacre unleashed such a firestorm of voter revulsion that the president would never again have sufficient popular support to govern effectively. Even before the so-called massacre, Alsop had quoted in his column an unnamed Nixon man as telling the Times, “The President is in no position to be telling Elliot Richardson what to do. That would just invite more cover-up charges.”

But the pivotal moment came with the Supreme Court’s unanimous decision over the matter of whether Nixon could be forced to turn over to prosecutors the tapes of his White House conversations. The Court said yes. Nixon, said the Court, could not claim any “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances.” The court made no effort to eviscerate the doctrine of executive privilege, but said it couldn’t be invoked in criminal proceedings except to protect military or diplomatic secrets.

That opened a path to a new doctrine—that the attorney general doesn’t work for the president. And this in turn paved the way for congressional mischief based on allegations that the attorney general isn’t serving his rightful boss, the people. We’ve seen this mischief in recent days with the hue and cry directed at Barr over his handling of the Mueller report. When the opposition didn’t like his judgments, it immediately accused him of serving his president over the people and zeroed in on what it decried as inappropriate and even illegal actions.

This isn’t a call for a reversal of the Court’s U.S. v. Nixon decision. The unanimity and reasoning of the ruling were compelling in 1973 and remain so today. But it is a call for recognition that this is not a simple matter. For separation of powers to work as conceived, the president must be able to protect his political interests and constitutional prerogatives, as Alsop recognized decades ago. The Russia-gate drama accentuates that need all the more, given that the whole thing was unleashed on the basis of allegations that proved to be largely bogus.

Just as executive power must be checked, so must legislative power. We don’t want a recurrence of the Andrew Johnson impeachment spectacle, when Congress passed an unconstitutional law, over Johnson’s veto, encroaching on the president’s ability to do his job, then impeached him for failing to comply with it. He came within a single Senate vote of being convicted.

Where’s the balance in this complex constitutional give-and-take? There are no hard and fast rules, and the magnitude and potential malignity of miscreancy must inform answers in any particular crisis. But we should begin with the recognition that the attorney general works for the president, and that that relationship shouldn’t be traduced or trampled upon except in severely extenuating circumstances.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington journalist and publishing executive, is the author most recently of President McKinley: Architect of the American Century.