Where Are All the Governors on the Democratic Debate Stage?

Remember the 2016 Republican presidential primary? Given the towering levels of self-medication required to get me through a 27-person CNN debate, I certainly don’t. But those in the know inform me that one of the major issues early on was whether to nominate a senator or a governor. The senators that year were the cream of the Tea Party class, freshmen with innovative ideas unafraid to stray from what had been the GOP party line. But the governors had an advantage of their own: executive knowhow, a proven record of having run something larger than an office in the Russell building.

A senator or a governor? In the end, Republicans went with neither. They opted instead for a bottled water tycoon who seemed to have the best of both: Trump was a good talker with a fresh outlook who also had experience running a company. Still, everyone knew the business empire was just so much gimcrack. The real reason Trump won was the senatorial one: he could gab. Even better, he could win rhetorical battles in a culture war that conservatives suspected their party’s establishment of having deserted long ago.

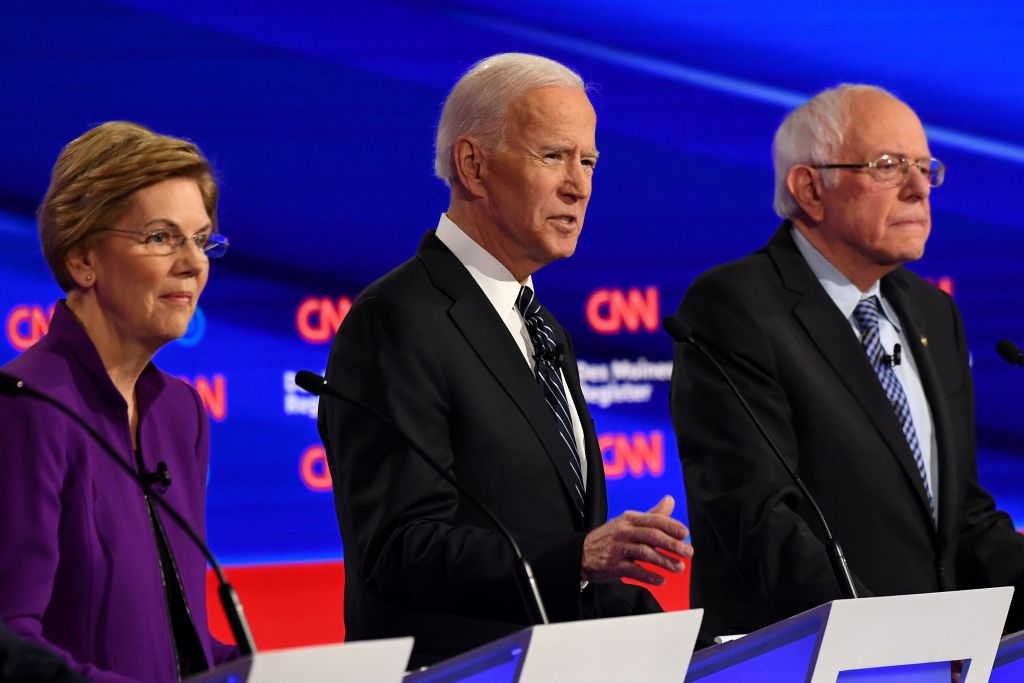

That was 2016—four years ago, or 5.7 billion years in Internet time. Yet fast-forward to today and the Democrats are facing a similar dilemma—except unlike the Republicans, they seem to have answered their “senator or governor” question before the primary even began. Of the six presidential candidates onstage at last week’s debate, four either are or have served as senators. In contrast, there wasn’t a single governor on the dais. Pete Buttigieg has some executive experience, though running a college town is hardly the same thing as governing a state. Joe Biden served as vice president, an executive office of a sort, though that only calls to mind the judgment of the glorious Texan John “Cactus Jack” Garner, FDR’s first veep: the vice presidency, Garner said, is “not worth a warm bucket of piss.”

Vice presidents cut ribbons with unnecessarily large pairs of scissors; governors run states. And except for maybe a stint in the Cabinet, there is no better on-the-job training for a future president. So why is the Democratic field so bereft of gubernatorial talent?

Part of the problem is that many of the governors on the Democratic bench haven’t been there very long. Prior to 2018, the nation’s governor’s mansions were overwhelmingly controlled by Republicans, as the Tea Party wave crashed on the heads of hundreds of statewide Democrats. Then two years ago, voters did an about-face: the 2018 midterms saw Democrats gain seven governorships, including in deep-red Kansas. Add Kentucky to their column in 2019, when Andy Beshear defeated then-governor Matt Bevin, and the Democratic gubernatorial count currently stands at 24 to Republicans’ 26, an oft-overlooked seismic shift. Still, a third of those Democratic seats have been blue for only a year or less, and unless you’re a self-styled messiah from Illinois, that isn’t long enough a wait before mounting a presidential run.

The most seasoned Democratic governors tend to come from the bluest states, and therein lies another problem: America’s liberal executives are a controversial bunch. They tend to be either too left-wing for the country as a whole or punching bags for their wrathful constituents (or both). Gavin Newsom of California is such an advocate of untrammeled government that even the LA Times thinks he goes too far. Gina Raimondo of Rhode Island is the least popular governor in the country. Dannel Malloy left a smoldering crater where the state of Connecticut used to be and his successor Ned Lamont isn’t any better. Andrew Cuomo is a lightning rod even by New York standards.

There’s also the matter of the ongoing blue state reckoning, as the tax-the-middle-class-and-spend-on-the-public-sector model starts to tear at the seams. That isn’t to say Republicans can’t foul up states too—there’s a reason Kansans turned their back on the GOP in 2018—but Democrats much more so are staring at a crisis of governance. Of the top five states that people are moving out of, according to data compiled by United Van Lines, four are reliably blue and three are in the Northeast. Expand the count to six, adding Massachusetts, and you include the homes of three of America’s most iconic cities—Chicago, New York, and Boston—an indictment given how many people are flocking to urban areas. Illinois is ever the basket case, a teetering Tower of Babel to fiscal promiscuity and corruption. Connecticut, meanwhile, seems trapped in a death spiral, raising taxes only to drive more people away and take in even less revenue than expected; rinse, repeat.

Governors running for president are all about touting chirpy successes, and right now there aren’t a lot of those coming out of New England or the West Coast. Still, Bill Clinton, a governor, won his party’s nomination in 1992, and his home state of Arkansas had plenty of problems. There’s something bigger than just local issues holding Democratic governors back, and that something is Bill Clinton himself, or at least what he’s come to represent. The brand of politics he inaugurated—or perhaps inherited from JFK and refined—is fundamentally more concerned with emotive imagery than policy success. Clinton hugged a voter at a debate and felt our pain; his successor George W. Bush declared himself a “compassionate conservative.” Today sentimental style still reigns, only the operative emotion has changed. It’s anger that’s au courant now, with ideas important to the extent that they can be juxtaposed with whoever is the enemy du jour on the other side. And anger needs communicating, a specialty of senators.

The result of such emotional politics is that the Democratic presidential field still has two wings, but they look different than they might have 30 years ago. The idealist wing has moved left, currently manned by democratic socialist Bernie Sanders and pathological liar Elizabeth Warren, neither of whom have much governing experience but both of whom come across as furious and good contrasts to Trump. The realist wing, meanwhile, held down by Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar, still touts its problem-solving acumen, though it’s mostly legislative rather than executive. The only (former) governor in the race, Deval Patrick, who touts his “practical experience” in Massachusetts, barely registers in the polls. Governor Jay Inslee of Washington briefly joined the pack, only to resort to pathetic stunts to try to get noticed before dropping out.

It’s tempting, then, to say that the senators have won. But it’s probably more accurate to say that Trump has won, that his anger-over-accomplishment, sizzle-over-(burnt)-steak ethos has infiltrated the Democratic Party too. I don’t intend any of this as an attack on senators-turned-presidents; I voted for Rand Paul in the 2016 primary and appreciate the role legislators can play in affecting intellectual and policy change. But we should remember that presidents ultimately have to govern. They have to run sprawling clusters of bureaucracy and manage millions of public servants. If they can’t, the administrative state is left to its own devices, anathema in a republic such as ours.

It would be grand to have a president whose main talent was governing rather than talking, who might even shut up and leave us alone and go do his job for a while. That isn’t likely to be Deval Patrick, though a certain Massachusetts predecessor of his does come to mind.