America’s First Fake News Panic

A new book examines the chaos Orson Welles and a new technology brought to America.

Dead Air: The Night That Orson Welles Terrified America, by William Elliot Hazelgrove. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, 249 pages.

For eight years after Donald Trump’s election in 2016, we were treated to an endless program of haranguing, censorship, and low-quality think-pieces about the dangers of misinformation, disinformation, and “fake news.” We have been conditioned to think of this as a new problem brought about by the internet and decentralized communication over social media; we have been assured the answer was more corporate and government control.

In reality, rumor and panic have always gripped societies, but every advance in communications increases the rate at which information, true or false, can be spread. In the book Dead Air: The Night That Orson Welles Terrified America, William Elliot Hazelgrove tells the story of one of the most famous episodes in American media history: Orson Welles’s notorious radio broadcast of The War of the World, which sent a panicking public into the streets, causing a fair amount of what today’s censors call “real-world harm.” Splitting the text evenly between the biography of the man and the event that would make him most famous, Hazelgrove cuts through the misinformation to tell an impressive, relevant story about how quickly a nation can lose its reason.

While most people have heard of this panic, few understand the story; many who have looked into it disagree about what happened. The event was obfuscated from the beginning because CBS entered crisis communications mode before the broadcast even ended. CBS even tried to prevent Welles from saying his coda, that it was a Halloween joke, for fear of liability for any harm caused by the broadcast. That was a substantial risk: People across the country had engaged in reckless behavior like drinking full bottles of whiskey or literally heading for the hills at breakneck speeds to get above the range of poison gas. Others fired guns at random objects, including everyday fixtures like water towers, fearing they were Martian spacecraft. Years later, a man assaulted Orson Welles in a hotel, saying his wife had killed herself during the broadcast.

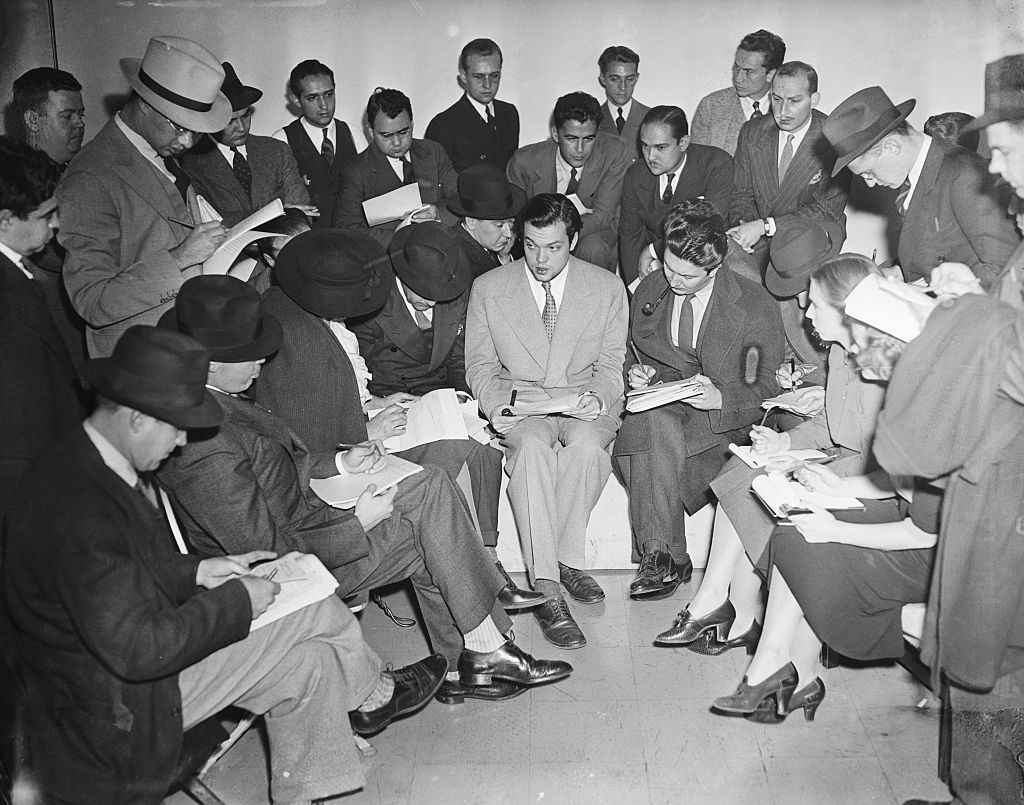

Further muddying the situation is that Welles, like many creative geniuses, had a tendency of giving contradictory statements, keeping an air of mystery about his creative process. However, in this particular instance, CBS used a technique we are familiar with: They dealt with problems they caused by fake news with more fake news. The next day a now-famous press conference expressing contrition for the “mistake,” one that Hazelgrove believes was staged, was filmed and distributed across the country. Later in life Welles would make several statements indicating that he had intentionally played a prank on America. The War of the Worlds was broadcast when Welles was 23. Although he was widely considered to be a master artist and always had multiple projects to talk about, it was rare that he had an interview where he was not asked about this program.

The biggest question, then and now: How did this happen? Why would the public believe that a radio broadcast about an invasion from Mars was real? One strength of this text is contextualizing American life at the time. While Americans had low faith in the newspapers because of the “Yellow Journalism” era, the new format of radio was highly trusted. Some Civil War veterans were still alive; the pace of change had been, if not greater than has been seen by 90-year-olds alive today, more unexpected. It wasn’t just the old or the uneducated who bought into the prank, despite the perception that has been passed down to us. Panics were recorded on college campuses and military bases. There were even Princeton professors who immediately drove to inspect the “crash site,” only four miles away, after hearing the broadcast. The reality is that the panic was widespread enough that it is referenced many times in declassified government UFO documents as the only example we have of how people might react to aliens invading.

In October 1938, recent events had primed the public to accept something as crazy as an invasion from Mars. The fiery crash of the Hindenburg the prior year was the first really bad thing ever captured live on broadcast media and was something like that era’s 9/11 in terms of the shock it produced for the public tuned into the broadcast. This lent credibility to supposed live coverage of a reporter being vaporized, despite its apparent improbability. Furthermore, the Sudetenland crisis, only a month before, had been the subject of marathon media coverage, and Americans were so on edge about war breaking out that some listeners ignored the word “Martians” and believed the Germans had attacked New Jersey.

Broadcast journalism had just been invented, so live news coverage was rare. Instead, radio dramatizations of news stories were common, with Orson Welles himself being a star of TIME magazine’s show dramatizing stories in their magazine. (Broadcasters agreed to end that practice following this event.) Though it is familiar to us, telling a dramatic story in the form of radio news dispatches had never been done, so it took a degree of abstract thinking to see through the deception. Even some listeners who had tuned in specifically for the “Mercury Theater on Air” show but had missed the brief introduction were fooled, as the program usually ran conventional radio plays. Others switched over and heard a “news” broadcast like no other. More importantly, the story went what we now call “viral,” with switchboards across the country tied up for hours and people running into churches during Sunday night services and announcing the apocalypse until almost everyone in the country had heard the “news.”

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Then, as now, no one could decide what to make of mass public gullibility. Newspaper articles were rushed out arguing different things. One key study in the immediate aftermath by Hadley Cantril analyzed 12,500 newspaper clips. There were countless angry letters to CBS, its local affiliates, the FCC, and to Welles himself telling of the writers’ experiences. Many letters seemed primarily to serve the purpose of ameliorating the writer’s feeling of foolishness by explaining why it was believable. Yet the strongest sentiment was to blame Welles himself, as an amoral and attention-hungry trickster unconcerned about the damage he caused. That is more or less Hazelton’s view of the situation, as well.

The popular liberal columnist Dorothy Thompson would ultimately win the War of the Worlds narrative wars—and save Welles—with a screed in the New York Herald-Tribune arguing that the problem was a lack of public education. She even claimed that Welles had done the country a favor by showing us how easily a totalitarian figure like Hitler could deceive and take over America. She seems to have based this on next to nothing besides her disdain for the common man, while entirely ignoring countless examples of people in her own social class who bought into the panic.

Dead Air is not the deepest book you will read. It is targeted at pleasure-readers, not researchers; nevertheless, it provides an adept retelling of a famous and poorly understood episode in American life. The relevance to our era is easy to see, and the author has enough faith in his readers to allow them for the most part to draw their own conclusions, instead of belaboring the obvious point about the dangers of misinformation in the 2020s. There is much value in the knowledge of just how little things change; the debates of the time about the responsibilities of broadcasters and the role of the government will be familiar to modern readers. Everyone likes to imagine society has matured past the possibility of having this sort of panic again, but I suspect, with the rapid development of AI, the occurrence of another such event may only be a matter of time.