America’s Return To Racism

I have been struggling to articulate my rising anger and despair over the way we think and talk about race in this country. This moving piece by Naomi Schaefer Riley over her fears of how the Great Awokening might screw up the heads of her biracial kids speaks to it surprisingly well. Excerpts:

A little more than a week after school ended in June, I ran into a friend who wanted urgently to know whether my children were okay. Her concern was not whether my middle-school son and daughter had caught the virus (she knew they hadn’t), or whether they had suffered from the isolation of a months-long lockdown, or even whether they had managed the stresses of online learning. No, she had just read on a local news website that my children’s school, Rye Country Day, was a hotbed of racial animus, and she was worried that my children, whose father is black, had suffered as a result. I laughed politely and assured her that they were fine. But the more I have thought about their experience over the past year at this elite prep school in Westchester, the more I wonder whether the racialized madness that has overtaken our country will leave any of us “fine”—and the more I have come to believe that these schools are, in fact, beset by racism. It’s just not the kind of racism they think.

I am not naive. When we decided to leave the world of our Jewish day school, I knew things would be different. I knew that at least some of the time spent on Judaic studies would be filled up with social-justice pursuits. I knew that our children would go from being seen as Jews who looked a little different from other Jews (and may have appeared in school brochures more frequently than other children) to children whose racial identity mattered considerably and whose religious identity was a secondary, if not a trivial, concern. But we had also been told that, of the public and private schools in our area, RCDS was among the most academically rigorous. Students not only got into top colleges, which was true at many other Westchester schools, but they took a lot of AP classes, had the option of studying classics, and were assigned a significant amount of homework.

Within the first week of school, though, it became clear that the school had other priorities—namely, “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” The kids were immediately offered the chance to join a variety of clubs, including a diversity club, a students-of-color club, and a girls-of-color club in which older girls of color mentored younger ones. Parents received numerous emails about these clubs, and our kids were invited on a number of occasions to join, including by their teachers. They did not.

I’m not going to quote from the vast middle of the piece — you really do need to read it for yourself. This elite private school has gone totally neurotic about the possibility of racism tainting its student body. It sounds like a miserable experience — nonstop ideological monitoring and messaging. She continues:

When I asked my children whether they experienced racism at RCDS, they laugh. Their classmates were never anything less than kind to them. Maybe any aggressions were too “micro” to be noticed. But the parents, too, seemed considerate and warm. And this, perhaps, is what worries me most. In the 13 years since I gave birth to my first child, I have sighed occasionally at the silly things people say to me—“What a nice tan your children have,” “What does their father look like?”—but the experience of being the mother of mixed-race kids has only confirmed to me that we are fortunate to live in the most tolerant, open-minded country in the world. There are parents at our synagogue, our schools, and in our neighborhood who have welcomed my children into their homes, who have fed them and cared for them, and who have treated them like family.

I fear that the message currently emanating from teachers and administrators and politicians and pundits will harm those relationships. The new anti-racism, with its endless cycles of victimization and demands for reparations—as opposed to the model of teaching people to aspire to colorblindness and providing everyone with equal opportunity—requires all of us (and children in particular) to see race all the time. This new model will turn what would otherwise be ordinary, healthy relationships—friendships, even—into dramas with racially defined roles for all the characters.

The good people of my community and others around the country are told that no matter how welcoming they are, how well they treat others, there is nothing they can do to make up for systemic racism. Will they begin to fret over every interaction, fearing that they could say or do the wrong thing? When the parents I know see a New York City education-council member screaming at a white man because he is bouncing the black child of a friend on his lap—as one activist, Rachel Broshi, did in a video of an online meeting that went viral—what will they think?

Read the whole thing. I strongly urge you to.

Why do I relate to this?

As most of my readers know, I was born in 1967, in the rural Deep South, in a parish (county) that was half black. I wouldn’t learn this till far into my adulthood, but the Klan still existed there when I was born, though it was fast winding down under FBI pressure. My generation was the first to go through integrated public schools there.

If you want to talk about “systemic racism,” well, I regret to say that the society in which I grew up was that, to some extent. I honestly don’t recall my parents ever teaching anything explicitly racist to me, and I imagine that most of my white peers would say the same thing about their childhood homes. But our parents didn’t have to. We all experience blacks (and they experienced us) as the Other. We went to school together, we shopped in the same stores, but that was about it. I remember in fourth grade (probably 1977), on one of the last days of school in the spring, the teacher passed out application forms for boys to join the Dixie Youth private summer baseball league. None of the black boys in our class got a form. I remember feeling embarrassed over that, but that quickly passed, because of course black kids weren’t going to play baseball with us.

We belonged to a private pool in town. It wasn’t fancy at all — all of us kids were middle and lower middle class people — but it was exclusively white. I can remember splashing around in the summertime there, and seeing black kids from time to time walk by and look at us through the fence. I remember feeling shame over that, but again, I put it out of my mind so I could enjoy the swim. That was just the way it was.

This is the way systemic racism worked to shape us kids, black and white, in the 1970s. There were other ways too, ways that continued after I left. I wrote about it this spring, when there was a protest movement in town — a protest movement for racial justice that my niece started, and that I publicly supported.

Now that I’m older, though, I can see that despite all our defects in the 1970s on race, the people of my town — white and black — were making real progress. The integration of the schools and the end of the apartheid Jim Crow system was a massive leap forward, something that would have been unthinkable only ten years before I was born. Nobody could have expected utopia instantly. The black kids had to give up their own schools to make integration work. The unified school system did what it could to get through the tumultuous change keeping everybody together. If I explain to people who didn’t grow up there that in my elementary school, there were five classes, three of them all-black, with all black teachers, and two of them mostly white, with a few black kids, their faces blanch. I can easily imagine, though, that this was necessary for the transition. Black parents didn’t want to give up their schools, but they had to — but at least they could keep their black teachers. White parents who had been raised in segregated schools no doubt felt anxiety about their kids going to school with black kids. Somehow the school administration — which included black people in positions of authority — had to make it work.

And they did. They built what has become one of the most successful public school systems in the state.

Anyway, I’ve thought a lot over the years about how very different the message that my generation got about race was from what our parents had. My mom and dad were in school in the 1940s and 1950s. Segregated schools. They grew up in what you might call an “information environment” in which white supremacy was the only reality. They never, ever heard it challenged — not on radio broadcasts, not in the newspapers, not in church, nowhere. Their children, though, were raised on television. We never (to my recollection) got any kind of proclamations of white supremacy; the adults just didn’t talk about any of it. But we did get, and got often, the message through television, and to some extent in the classroom, that the color of your skin doesn’t matter — it’s all about the content of your character.

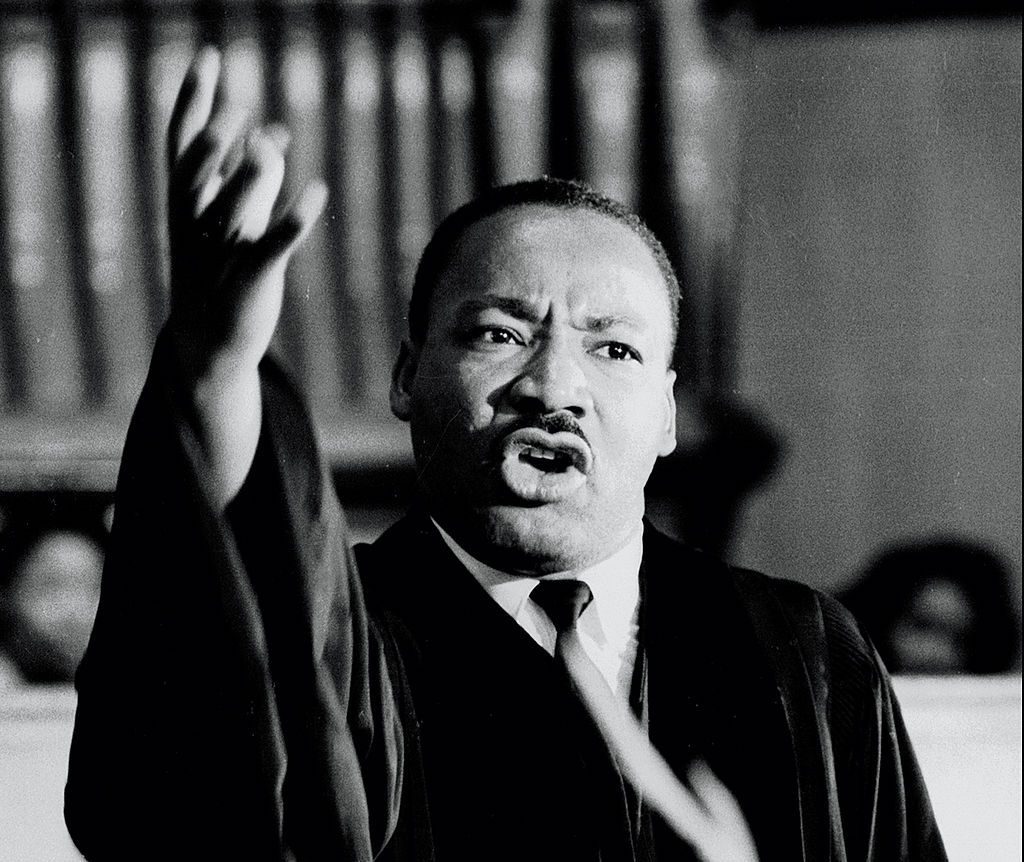

This was a radical message for us! Can you imagine that the local culture, since the area was first settled in the 1700s, had been built around the idea of racial difference, and the superiority of whites to blacks — first with slavery, then through Jim Crow. Then suddenly, with my generation, all of that changed. It changed because Martin Luther King, Jr., and his disciples preached the gospel — and demanded that not only America live up to the promises of its Constitution, but that white Christians live up to the commands of Our Lord.

Dr. King didn’t just set the black people of America free; he set us all free. What liberty to be told that you shouldn’t judge a person by the color of their skin — that we are all brothers and sisters underneath. The men and women of my mom and dads generation didn’t have that liberty. My generation did. It did not bring us to Paradise — a paradise that is impossible on this earth — but it did finally start us on the road to greater equality.

What a blessing to have children, raised in the South, who find it completely bizarre that once upon a time, in their grandparents’ generation, there was legal discrimination against black people. Once a child of mine asked if blacks and whites could marry back then. No, I told him, they couldn’t. But you kids, the only thing your mom and dad care about is that you marry within our faith. My late sister’s daughter is engaged to be married to a man from Colombia — a good man whom she met at church. He is Latino, but has skin darker than some black people in our town. And we love him, in our family, without reservation. Two generations ago, that kind of marriage would have been impossible there. This is progress! The burden of judging people by the color of their skin is being shaken off — imperfectly, God knows, but there it is.

And now look. It’s coming back with a vengeance — from the left. All the things that the Civil Rights Movement worked for — the change of consciousness — is being thrown in the ditch by progressives on the Long March to Paradise. They are condemning new generations to think constantly about race and racial difference, to believe that it is impossible to judge people in any other way. I will be damned before I allow my children to believe that they are better than anybody because they are white, or that they are worse than anybody. The good people in my mom and dad’s generation had to fight the racists of the Right in power for the sake of colorblindness. Now good people have to fight the racists of the Left for the same reason.

How infuriating, and how tragic, it is to hear coming out of the lives of left-wing people ideals that essentially confirm what white segregationists once thought, and taught. Will it have just been a moment in our country’s history, when we tried, really tried, to see not color, but character as the measure of a man’s worth?

I was e-mailing with a reader of this blog, a white Christian man in his 60s who is married to a black woman. We’re both Southerners. I want to quote this passage from his e-mail:

Our generation was the bridge between Jim Crow — which existed in all its ugliness when we were children — and the racially-integrated world. I have no doubt that the approach at Martin Luther King, Jr., took was successful, for it forced whites to look into the mirror and see all sorts of violence and ugliness. We didn’t do it perfectly or even well, but nonetheless the racial attitudes that had endured for generations were broken, and I credit the non-violent movements for allowing people to break through the barriers.Wokeness, and especially Wokeness in the Church is not a continuation of what happened 50 years ago. The appeals to ending racism in the Church were made through Scripture, through St. Paul imploring believers to remember that in Christ, there was no Greek nor Gentile nor Jew, no male nor female, but all were one. The message was an appeal to grace, not to prejudice. However, look at Wokeness with its ultra-fundamentalist approach; it condemns and offers no grace except the “grace” that comes when one “loves Big Brother.” There is no redemption, only submission, and it is much more like Islam than Christianity. In so many ways, it reminds me of the graceless and angry fundamentalism of my childhood when places like Bob Jones University preached a gospel utterly incompatible with Scripture. All “heretics” are shunned and thrown into the Outer Darkness (where there will be found weeping and gnashing of teeth). …The movement Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. began appealed to grace; Wokeness does not, as it is the polar opposite of grace. When Christian churches accept this way of thinking, they abandon the one thing that makes the Gospel stand out from everything else and replace it with a system of shaming, anger, hatred, and no hope of redemption.